the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Thermobarokinetics of ice: constitutive formulation for the coupled effect of temperature, stress, and strain rate in ice

Faranak Sahragard

Mehdi Pouragha

Mohammad Rayhani

Understanding and modeling the mechanical behavior of ice under varying thermal and loading conditions is essential for cryospheric science, permafrost engineering, and the design of polar infrastructure. A central challenge lies in capturing the strong coupling between stress, strain rate, and temperature, an interdependence referred to in this work as the thermobarokinetics of ice. This study presents a three-dimensional constitutive model that explicitly incorporates this coupling through a unified thermomechanical framework. Notably, the model employs shared functional dependencies for both viscosity and damage initiation, allowing key rate- and temperature-sensitive processes to be represented using a minimal set of physically interpretable parameters. Damage evolution is governed by an energy-based law that depends on strain rate and temperature. The model is calibrated and validated against triaxial compression and relaxation test data on polycrystalline ice, demonstrating its ability to capture salient features of ice mechanics such as ductile to brittle transitions, strain-rate-dependent strength, stress relaxation, and thermal softening. In addition, a novel healing mechanism inspired by viscous sintering is introduced, in which the rate of damage reversal is driven by viscous energy dissipation and modulated by pressure and temperature.

- Article

(2365 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Accurate modeling of ice mechanics is essential in a wide range of disciplines, including glaciology, cryospheric science, geotechnical engineering of cold regions, and permafrost engineering. However, developing robust constitutive models for ice remains a challenge, primarily due to the multitude of relevant physical processes and parameters, and the complex, often nonlinear interactions among them. In particular, the strong coupling between pressure, strain rate, and temperature effects makes it exceedingly difficult to isolate individual mechanisms for separate analysis and modeling – as is more commonly feasible for other natural solids such as metals or soils. For instance, careful experimental studies have shown that strain rate dependency in ice not only induces creep and relaxation behavior, but also affects the yield stress and can influence the brittle or ductile nature of failure (Jones, 1982; Jones and Chew, 1983; Durham et al., 1983; Schulson, 1990; Murrell et al., 1991; Kalifa et al., 1992; Rist and Murrell, 1994; Gagnon and Gammon, 1995; Gratz and Schulson, 1997; Sammonds et al., 1998; Mizuno, 1998; Meglis et al., 1999). Similarly, pressure influences not only the yield stress of ice but also its viscous behavior, while temperature affects nearly all mechanical properties, including stiffness, yield strength, and viscosity. The intertwined effects of temperature, pressure and strain rate introduce strong nonlinearities into the material response that cannot be captured by simple additive formulations. Consequently, the reliable interpretation of experimental data and in-situ observations demands a theoretical framework that accounts, at least partially, for the coupled influence of these parameters. For example, in geotechnical engineering, it is not uncommon to interpret the failure of frozen soils or ice using cohesive-frictional Mohr-Coulomb criteria, without adequately considering the underlying viscous mechanisms. However, the friction and cohesion values derived in this way are inherently limited in accuracy and are unlikely to remain valid when extrapolated beyond the specific experimental conditions under which they were obtained.

By nature, ice exhibits behaviors characteristic of fluids, granular materials, and crystalline solids. It is therefore not surprising that constitutive models developed in these fields have been adapted and extended to describe the thermomechanical response of ice. Some instances include: ice models based on rheological models for the viscous flow (e.g., Nye, 1953; Glen, 1955; Nye, 1957; Azuma, 1994); models based on granular flow (e.g., Wilchinsky and Feltham, 2006; Herman, 2022; Ren et al., 2025); models based on granular solids (e.g., Balendran and Nemat-Nasser, 1993; Tremblay and Mysak, 1997); and extensions to the crystal mechanics models (e.g., Michel, 1978; Cole, 1995, 1998, 2020).

Combining various physics such as viscosity, elasticity, and plasticity is commonly achieved through using rheological models built from various configurations of springs, dashpots, and frictional elements. One common approach is the so-called Burgers body model, which consists of a Maxwell element in series with a Kelvin element. In this model, total strain is decomposed into instantaneous elastic, delayed elastic, and permanent viscous components. One of the earliest applications of such a viscoelastic model to ice is found in the work of Sinha (1978), who developed a one-dimensional formulation to capture the creep behavior of ice under constant stress. The delayed elastic response was expressed as a function of both time and temperature, while Glen-Nye flow law (Nye, 1953; Glen, 1955) was employed to describe the viscous strain. Subsequent developments extended the model to three-dimensional stress and strain states and incorporated damage mechanisms. For example, Karr and Choi (1989) introduced a damage parameter to capture anisotropic microcrack evolution, accounting for its dependence on stress and strain rate. Later, Duddu and Waisman (2012) elaborated on this model by incorporating temperature-dependent viscous strain, though their formulation remains limited to low stress levels and strain rates. Another notable three-dimensional version of the Burgers model was developed by Xiao and Jordaan (1996), who employed nonlinear dashpots following a power law in both the Kelvin and Maxwell elements. Their approach integrated Schapery's viscoelastic damage theory (Schapery, 1991) to represent creep-induced damage and accounted for the suppressive effect of confining pressure on microcrack growth. However, this model did not explicitly include temperature effects. More recently, Xu et al. (2019) incorporated plasticity into the Burgers model. Their formulation included temperature-dependent strain rates for both delayed elastic and viscous components. The influence of confining pressure was also captured: strain rate was found to decrease with increasing pressure up to 50 MPa, beyond which it increased. Nevertheless, this model remains limited to ductile deformation and does not address brittle damage mechanisms.

Developing multi-mechanism constitutive models involves a careful balance between the complexity of the overall rheological configuration and the sophistication of the individual constitutive formulations that represent each mechanism. This balance becomes especially important when accounting for the coupling between mechanisms, which is typically embedded within the constitutive description of each component. Indeed, in some cases, simpler rheological elements, such as Maxwell units, are also successfully employed to model the behavior of ice. One prominent such example is found in the works of Dansereau and coworkers (Dansereau et al., 2016, 2017; Olason et al., 2022) who introduced a Maxwell elasto-brittle model for sea ice that incorporates the evolution of both the elastic modulus and the viscosity, while simultaneously accounting for damage and healing mechanisms. Despite its relative simplicity, the model offers unique advantages due to its minimal number of parameters, straightforward configuration, and the incorporation of a healing effect essential for accurately simulating ice behavior under long-term loading and high pressure conditions (Brodeau et al., 2024). Some of the simplifications particular to sea ice adopted in this model include temperature independence, a Mohr-Coulomb damage initiation function excluding damage under isotropic stresses, and time-driven damage and healing evolution laws.

A review of the existing literature on constitutive modeling of ice points to the persistent challenge of accurately formulating the coupling between stress, strain rate, and temperature effects. While the general frameworks of rational mechanics for these couplings is laid out in monographs such as Hutter (2020), in practice, the existing constitutive models for ice often struggle to coherently integrate these interactions. As a result, their applicability is typically confined to a narrow range of conditions, such as specific temperatures or loading regimes, thereby limiting their generalizability across the wide spectrum of scenarios encountered in cryospheric and engineering applications.

In this study, we aim to develop a three-dimensional constitutive model for ice that addresses key shortcomings of existing approaches and introduces an integrated formulation to capture the combined effects of temperature, pressure, and strain rate; referred to here as the thermobarokinetics of ice. The model builds on the Maxwell elasto-brittle framework developed by Dansereau et al. (2016), with several key improvements including stress and temperature dependent viscosity, energy-driven damage, and temperature and rate dependent damage initiation limit, while keeping the model parameters manageable. A deliberate effort was made to integrate existing constitutive formulations from the literature into a coherent framework, rather than introducing entirely new modeling components. We adopt the Glen–Nye flow law (Nye, 1953; Glen, 1955) as a non-Newtonian viscosity model, combined with an Arrhenius-type expression to capture the temperature dependence of both viscosity and the energy threshold for damage initiation. Comparisons with available experimental data on ice support the plausibility of the proposed constitutive model in reproducing key features of ice behavior across a range of pressures, temperatures, and strain rates. Additionally, we propose a formulation for the healing process, drawing inspiration from viscous sintering phenomena observed in materials such as glass and magma.

Throughout this article, we use bold characters (e.g. I and ε) for second-order tensors, and hollow characters (e.g. ℂ) for fourth-order tensors. The colon symbol : represents a double-contraction, i.e. and , while the symbol ⊗ represents dyadic product, i.e. is equivalent to Cijkl=AijBkl. The second-order tensor of infinitesimal strain, ε, and the Cauchy stress σ can be divided into their spherical and deviatoric parts:

where εvol is the volumetric strain, e is the deviatoric strain tensor, εq is the deviatoric strain, p is the mean stress, s is deviatoric stress tensor, q is the deviatoric stress, and I is the second-order identity tensor. A fourth-order identity tensor, 𝕀, is also defined as with δ being the Kronecker delta. Finally, the over-dot represents the time-rate.

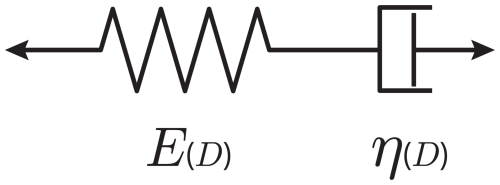

The sea-ice model by Dansereau et al. (2016), used as a starting point herein, adopts a viscoelastic Maxwell configuration, as shown in Fig. 1, including also a damage mechanism. The damage initiation is described by a non-evolving Mohr-Coulomb criterion in terms of the undamaged stresses, while the stress, elastic stiffness, and the Newtonian viscosity are prescribed to degrade with damage. Temporal evolution of the damage is explicitly given in the model, with damage reversal, or healing, also made possible through a constant healing rate.

Figure 1Schematic of the one-dimensional Maxwell model for a continuum material with elastic modulus E and viscosity η. Both elastic modulus and viscosity depend on the damage level, D.

The model developed in this study also adopts a similar viscoelastic Maxwell configuration which implies that the two mechanisms (i.e. viscous and elastic) share a stress while the strains are added:

with the superscripts “e” and “v” representing elastic and viscous mechanisms. The viscosity formulation presented later will indicate that the viscous strain, εv is traceless and deviatoric, implying that the volumetric strain is only due to the elastic component, i. e. .

Using the effective stress concept from damage mechanics and the principle of strain equivalence, the elastic energy density, ψ, of the elastic component under isothermal conditions is expressed as (Lemaitre and Chaboche, 1994; Chaboche, 1987):

where ℂe is the elasticity tensor for undamaged material, and describes the damage level. The inclusion of the 1−D indicates the release of elastic energy as a result of damage accumulation. Elastic Cauchy stress is defined as the conjugate to the elastic strain:

where σ* is the undamaged stress tensor. A thermodynamic force, Y, is also defined as the conjugate to the damage parameter D, which represents the damage driving force within the material:

The thermodynamic force, Y, corresponds to the rate of elastic strain energy released per unit increase in damage within the material (Chaboche, 1987), which is equivalent to the elastic strain energy in the undamaged state of the material. An isotropic elasticity is adopted in this study, with the elastic modulus given as:

with E being elastic Young's modulus of the undamaged material, and ν being the Poisson's ratio. The literature on the potential effects of temperature on the elastic stiffness of ice remains inconclusive, with experimental interpretations often influenced by the specific constitutive models employed. Some studies (e.g., Sinha, 1989) suggest minimal effect of temperature on elasticity, and that, to a good approximation, the elastic stiffness of ice can be assumed to be independent of temperature. In the present study, we adopt this assumption of thermal independence for the elastic moduli. Should temperature dependence be introduced, it must be done with particular care, ideally beginning with a temperature-dependent free energy formulation, to ensure thermodynamic consistency.

Substituting Eq. (6) into (4) gives the familiar isotropic stress-strain relationship:

3.1 Stress-dependent viscosity

The viscous behavior of ice is known to be non-Newtonian (Nye, 1953; Glen, 1955). Herein, we adopt the well-known Glen–Nye flow law for glacial ice that postulates a power law expression for the creep of polycrystalline ice based on compression tests on ice specimens. Following previous studies (Nye, 1957; Kenny, 1992; Xiao and Jordaan, 1996; Alaei et al., 2021), we assume that the viscous strain is only deviatoric and co-linear with the deviatoric stress. Moreover, following the assumption of Dansereau et al. (2016), the viscosity is assumed to degrade with a factor of (1−D)α with α>1 being a model constant, to ensure that the relaxation time decreases with damage. Therefore, the original Glen–Nye flow law can be extended to multiaxial conditions to read (Nye, 1953):

where A is a material constant, Q is the activation energy for creep, R is the universal gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, n is a model exponent, s is the deviatoric stress tensor and q is the deviatoric stress, defined in Sect. 2. The exponent α>1 distinguishes between the rate of degradation in elastic moduli and viscosity, with the former decreasing by (1−D) while latter decreases with (1−D)α. The temperature dependency in Eq. (8) is given by an Arrhenius-type expression, which can be translated as temperature and stress (or rate) dependent viscosity, η expressed as:

with being the rate of the deviatoric strain defined in Sect. 2. The second part of the equality, expressing viscosity in terms of the strain rate, can be derived recalling the co-linearity of the two tensors and s implied by Eq. (8). For future purposes, we denote by g(T) and the functions expressing the temperature- and rate-dependency, or thermokinetic, of viscosity:

3.2 Damage initiation criterion

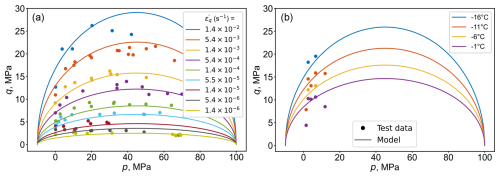

Experimental results show that the failure strength of ice exhibits thermobarokinetic dependency where it depends not only on confining pressure but also on temperature and strain rate (Jones, 1982; Kalifa et al., 1992; Rist and Murrell, 1994; Gagnon and Gammon, 1995; Mizuno, 1998; Meglis et al., 1999). The effect is presented in Fig. 2a and b where the maximum deviatoric stress is plotted versus the corresponding mean stress during triaxial compression tests performed by Jones (1982) and Gagnon and Gammon (1995). This peak deviatoric stress is often interpreted as the threshold beyond which damage starts. A number of key observations are derived from these experiments:

-

The failure (damage initiation) envelope is non-linear.

-

The threshold is thermobarokinetic.

-

Both the shear strength and its pressure-dependency seem to vanish at lower strain rates.

-

While not presented here explicitly, a brittle failure is reported for tests at lower mean pressures and higher strain rates, which switches to ductile when pressure is increased and/or strain rate is decreased.

Figure 2Variation of the peak deviatoric stress with confining pressure from triaxial compression tests on ice; (a) data from Jones (1982) at at various strain rates, and (b) data from Gagnon and Gammon (1995) showing the effect of temperatures.

These findings highlight the intertwined effects of strain rate, confining pressure, and temperature in determining both the strength of ice and its transition from brittle to ductile failure. Moreover, at high confining pressures, typically exceeding 40–50 MPa, the deviatoric strength of ice decreases with further increases in the mean pressure. This phenomenon is attributed to pressure melting and dynamic recrystallization, which occur as a result of stress concentration at grain boundaries (Jones, 1982; Jones and Chew, 1983; Rist and Murrell, 1994; Jordaan et al., 1999; Barrette and Jordaan, 2001).

Various yield and failure criteria have been proposed to improve the accuracy of ice failure strength prediction (e.g., Nadreau and Michel, 1986; Fish, 1992; Nadreau et al., 1991; Derradji-Aouat, 2000, 2003). In this study, we adopt an elliptical failure criterion similar to the yield surface in Cam-Clay models, which has also been used previously by studies such as the one by Derradji-Aouat (2000), and can be expressed in the q−p stress space as:

where p0 and pc are model constants representing the mean stress at ellipse center and major radius of ellipse, respectively, and qmax is the minor radius of the ellipse. Any effect of the third stress invariant (Lode angle) is ignored in this study.

The failure criterion developed by Derradji-Aouat (2000) accounts also for the influence of temperature and strain rate, and confining pressure on ice strength through making the parameter qmax in Eq. (11) depend on temperature and strain rate. We adopt the same strategy but avoid compounding model parameters by assuming the temperature-, and rate-dependency (thermokinetics) of qmax be similar to that of the viscosity described by Eq. (10), as follows:

where is a dimensionless model parameter. Note the slight difference that Eq. (12) depends on the total strain rate, while Eq. (10) is in terms of the viscous strain rate. The reason is that using either viscous or elastic strain rates will lead to the unrealistic vanishing of qmax either at the beginning of the deviatoric loading (), or at the steady state (). Nevertheless, following the principle of parsimony in model building, Eq. (12) renders the damage initiation, and the peak deviatoric stress thermokinetic without introducing any new model parameters. Our assumption that the viscous and damage mechanism share in their thermokinetic nature is consistent with previous observations that point to a correlation between the two mechanism, and more specifically a correlation between the minimum strain rate in a creep test and the failure strength in a constant strain rate test (Mellor and Cole, 1982; Sinha et al., 1995; Barrette and Jordaan, 2003). The form of Eq. (12) implies that the shear strength vanishes as the strain rate approaches zero, which is consistent with the observations made from the experimental data in Fig. 2.

Restricting the thermokinetics to qmax in Eq. (11) also implies that the minimum and maximum mean pressures (vertices along the major axis) remain independent of strain rate and temperature, which is more or less consistent with the general trends observed in the data in Fig. 2. The maximum mean stress is assumed to depict the pressure melting phenomenon, which is often considered to be independent of strain rate and temperature. The same is assumed to be applicable to the minimum mean stress describing the tensile hydrostatic strength of ice. Figure 2a and b showcase the capability of the proposed damage initiation model to capture the experimental trends, with the calibrated parameters presented later on in Table 1. Interestingly, the model performs reasonably well in capturing the thermokinetic damage initiation without resorting to additional calibration parameters. Further exploration of the model in later sections also demonstrate how the transition between brittle and ductile failure is captured by a combination of the Maxwell configuration and the rate-dependency of damage initiation.

It is worth mentioning that introducing such a rate-dependency directly into the yield surfaces that are subject to consistency condition () requires non-trivial constitutive and numerical treatment, as discussed by Voyiadjis and Abed (2006), among others. The discussion, however, is beyond the scope of the current study.

3.3 Energy-based damage evolution law

The model by Dansereau et al. (2016) adopts a stationary damage function independent of D, which requires explicit introduction of damage evolution law for the damage parameter. A more consistent alternative is to introduce the dependency on D into the damage initiation function to arrive at a formulation similar to the yield function in elastoplasticity framework, and derive the damage evolution law from the consistency requirement (Simo and Ju, 1987).

Drawing an analogy with elastoplasticity theory, we define a yield function f in terms of D and its conjugate Y which is based on the simple general form proposed by Marigo (1982):

where and are the undamaged elastic bulk and shear moduli, σ* is the undamaged stress tensor with p* being its mean stress, κ0 represents the threshold energy, independent of damage variable D, required to initiate damage growth, and m≥0 is a model constant. The expression for κ0 in Eq. (13) is derived by noting that at D=0, the expression of f should revert to the damage initiation function given in Eq. (11), and recalling that for isotropic elasticity, . The condition f≤0 requires that during yielding, the state of the material remains on the f, which is described by the consistency equation df=0:

where denotes a change in the deviatoric strain rate. Recalling , Eq. (14) can be rearranged to calculate the damage evolution dD that is required for the material state to remain on the yield surface:

which can be rewritten for clarity as:

The first term in Eq. (16) represents the damage evolution due to change in elastic strain while the second term accounts for the change in damage level as a result of change in strain rate and temperature. Kuhn–Tucker condition requires that damage evolution (yielding) occurs when , otherwise, the damage remains constant, unless healing is activated, as discussed in Sect. 5.

Equation (16) can now be substituted into the incremental form of Eq. (4), which, together with the total strain partitioning for Maxwell configuration, , leads to the following general incremental stress-strain relation:

with

The second expression in Eq. (18) also describes load reversal (unloading) under constant D.

The incremental form of the constitutive model is described in its entirety by Eqs. (17), (18), (16), (13), (12), (8), and (6). The system of equations is solved using explicit numerical integration method. Sensitivity tests were performed to confirm that the selected timesteps were sufficiently small, and further step-size reduction produced no meaningful change in the results.

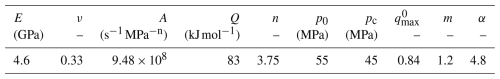

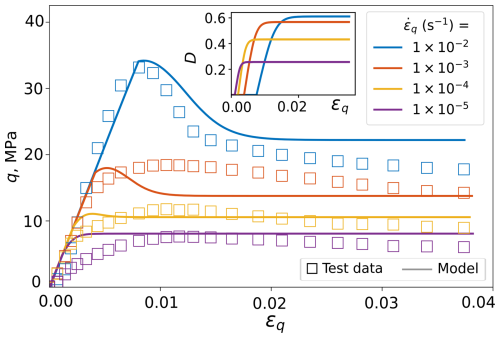

The model parameters are calibrated using multiple datasets on triaxial compression of ice; the parameters introduced for the damage initiation function, i.e. Q, n, A, p0, pc and in Eqs. (11) and (12), were calibrated using the datasets from Jones (1982) and Gagnon and Gammon (1995) with the predictions already presented in Fig. 2. The rest of the model parameters, E, ν, and m, describing the transient response with strain, are calibrated based on the triaxial dataset by Rist and Murrell (1994) who performed triaxial compression tests at a constant confining pressure of 10 MPa, with strain rates ranging from to at a temperature of −20 °C. The elastic parameters, E and ν, are calibrated directly based on the instantaneous stress-strain slopes, while the combination of parameters A and Q were fine-tuned based on the variation of the steady state stress with strain rate. The remaining parameter m controlling the damage evolution is calibrated based on the post-peak softening rate. The calibrated material parameters are compiled in Table 1.

The parameters are calibrated for isotropic, freshwater polycrystalline ice. Under this assumption the literature indicates a comparatively narrow band for elastic constants, with Sinha (1989) reporting E≈8.93–9.53 GPa and ν≈0.308–0.311 over 0 to −50 °C. The Maxwell configuration excludes the reversible rate-dependent deformation (primary creep), which is known to lead to lower calibrated Young's modulus values when compared to commonly reported literature values. For the Glen–Arrhenius set , reported values show bounded variability with n≈2–4, Q≈60–120 kJ mol−1, while A spans orders of magnitude across studies due to microstructure and differences in calibration windows (Glen, 1955; Barnes et al., 1971; Zeitz et al., 2020). Within this context, our calibrated lie within established intervals and are consistent with ranges reported by Durham et al. (1983) for polycrystalline ice.

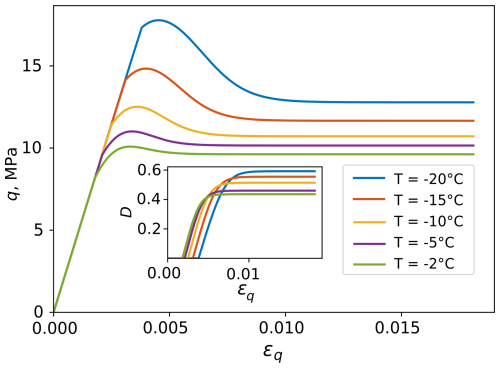

Figure 3 compares the model predictions with the experimental results with different strain rates, where an acceptable accuracy is observed in capturing both the maximum and residual deviatoric stresses as they vary with the imposed strain rate. The transition from ductile to brittle failure as a result of higher strain rates is also appropriately represented in the model. The evolution of the damage parameter is also given as an inset in Fig. 3 which indicates the effect of strain rate on damage initiation strains and the eventual damage value at steady state. Referring back to Eq. (9), the viscosity scales with q1−n, which together with the calibrated value of n>1, indicates that the viscosity becomes infinity at the start of the loading when q=0. This implies that the instantaneous response is elastic. The viscous mechanism becomes gradually more significant as q increases, and particularly after the damage mechanism starts. The degradation of viscosity with damage causes the viscous mechanism absorb more share of the imposed deformation rate, until a balance is reached at a particular damage level whereby at a constant strain rate, all the imposed deformation is accommodated by the viscous mechanism which remains at equilibrium with the stationary stress induced within the elastic mechanism.

Figure 3Comparison between the calibrated model results and triaxial compression data from Rist and Murrell (1994) at −20 °C and 10 MPa confining pressure for various strain rates. The inset shows the associated change in the damage parameter.

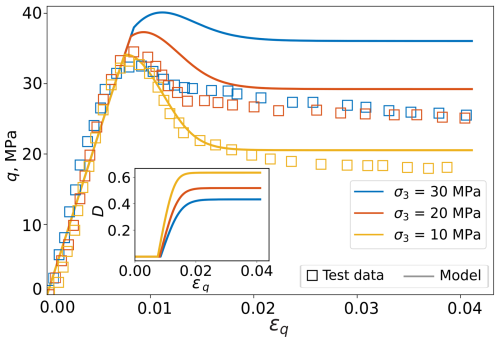

For further validation, the calibrated model is used, without any additional adjustments, to predict a separate set of triaxial experiments conducted by Murrell et al. (1991). These tests were performed under confining pressures ranging from 10 to 30 MPa, at a fixed strain rate of , and at the same temperature of −20 °C as in Rist and Murrell (1994). Figure 4 shows the stress-strain results for different confining stresses. While the lack of direct calibration causes the model to be less accurate compared to the results in Fig. 3, nevertheless, the model shows a plausible performance in capturing the peak stress and the pressure dependency of the failure nature, as it transitions from brittle to ductile for larger confining stresses. Compared to the experimental data, the model exhibits a higher sensitivity of the peak stress on the confining pressure, which, we conjecture, arises from the elliptical failure envelope used for peak stress prediction. The additional sensitivity of the residual stress is probably a secondary effect caused by the extra sensitivity of the peak stress. The evolution of the damage parameter D is also presented in Fig. 4 as an inset. Unlike that in Fig. 3, the fixed strain rate causes the damage mechanism to start at relatively the same strain level. The model successfully captures the well-known phenomenon of damage growth suppression, leading to lower level of damage, and hence more ductility, at higher pressures.

Figure 4Comparison between calibrated model results and triaxial compression data from Murrell et al. (1991) at −20 °C with a strain rate of under different levels of confining pressure. The inset shows the associated change in the damage parameter.

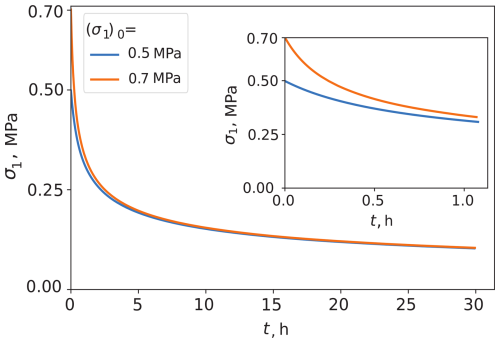

To better visualize the rate-dependent characteristics of the model, the same calibrated model has been used to simulate a relaxation test under uniaxial condition where the deviatoric stress is first increased to an initial value of (σ1)0 at . The stress is then allowed to relax under fixed strains. The temperature and the stress conditions are chosen to resemble the conditions reported in the study by Voitkovsky (1967). The relaxation of the stress for the two initial deviatoric stresses is shown in Fig. 5. The general trends of stress relaxation resembles those reported by Voitkovsky (1967). The half-relaxation times (i.e., time required for stress to drop to ) are found to be 2.2 and 0.89 h for the cases with (σ1)0=0.5 and 0.7 MPa, respectively, which are in general agreement with the ranges of 0.58–1.7 and 1.6–3.2 h reported by Voitkovsky (1967) for the same stress levels.

Figure 5Relaxation of deviatoric stress under fixed strains, uniaxial condition at , similar to the experiments reported by Voitkovsky (1967). The inset figure shows a zoomed view of the first hour.

The rate-dependency of the model makes it difficult to properly simulate a stress-controlled loading, similar to creep tests, where the change in strain rate ( required for the consistency equation) continuously evolve and is unknown. This issue, however, does not prevent implementation of the model in computational boundary value problem solvers that are often formulated in terms of imposed strains and strain rates. A constant stress can be achieved through a servo-control mechanism, which has not been considered in this study. However, if a constant strain rate is achieved under isothermal constant stress conditions, then the damage level will be stable and the dσ=0 will imply that the total strain rate is equal to the viscous strain rate, which is described by Eq. (8), which indicates a scaling of . This echoes the previous studies on the tertiary creep of ice whereby a similar scaling was reported (Paterson, 1977; Weertman, 1983; Treverrow et al., 2012), with an exponent of reported by Treverrow et al. (2012), which includes the value of 3.75 obtained through our calibration in Table 1. Nevertheless, the Maxwell configuration used in the current model is known to produce a two-stage creep response under constant stress conditions, as opposed to the three-stage creep behavior commonly recognized in the literature (Paterson, 1977).

4.1 Parametric explorations

As a parametric study, the effect of varying temperatures on the stress-strain predictions is visualized in Fig. 6 for triaxial compression conditions with a confining pressure of 10 MPa and a constant strain rate of . With the inclusion of temperature dependency into both the damage yield function and the viscosity formulation, the model captures the general observed trends of increase in strength and the decrease in ductility for lower temperatures.

Figure 6Effect of temperature on predicted stress–strain response of triaxial compression under 10 MPa confining pressure and a constant strain rate of . The inset shows the associated change in the damage parameter.

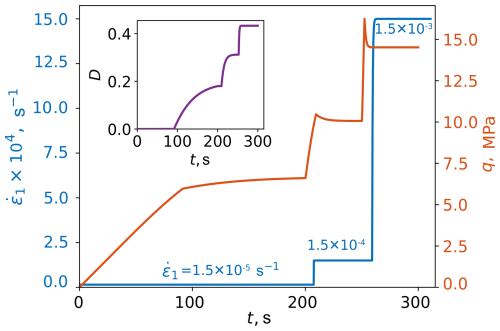

The effect of varying strain rate on the deviatoric stress is visualized in Fig. 7 for a triaxial compression test where the axial strain rate is increased in two steps from to . The higher strain rate induces higher deviatoric stresses through the combined effect of a higher viscous stress and the expansion of the damage yield function. The response also becomes more brittle at higher strain rates, as is expected. The evolution of damage parameter is also presented as an inset in Fig. 7 where the increase of damage with strain is a further indicator of the increased brittleness. Note that the rate-dependency of the damage mechanism and the inclusion of in the consistency relation (Eq. 14) prevents the possibility of jumps in strain rates, and as a result, short periods of smooth transitions are included to ramp up the strain rate.

Figure 7Deviatoric stress response of a triaxial compression under σ3=10 MPa and a constant temperature of . Axial strain rate is increased in two steps from to . The inset shows the associated change in the damage parameter.

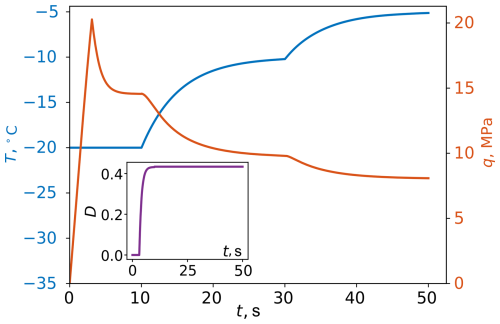

To better demonstrate the capability of the proposed model in capturing complex loading paths, we consider a condition where the temperature is changing while the material is under constant strain rate. The variation in the deviatoric stress and temperature with time is shown in Fig. 8 where the temperature is increased from to −5 °C under a constant strain rate of . As expected, the deviatoric stress gradually decreases as the temperature raises, indicating a degradation in ice strength. The inset of Fig. 8 shows the variation of the damage parameter, which, interestingly, does not further increase when the temperature is increased and the deviatoric stress drops. This is due to the sample becoming more ductile at higher temperatures, which precludes further damage. Instead, the stress states glides along the yield surface that is shrinking as the temperature is increased.

Ice, like many crystalline materials, particularly those with a granular structure, exhibits the capacity to heal after fracturing, regaining strength and stiffness over time (Miao et al., 1995). The healing of ice is an active area of research and is generally regarded as a thermally activated process, driven primarily by surface energy minimization through mass transport (Blackford, 2007). Among the proposed mechanisms, sintering via surface diffusion is considered the dominant mode of crack healing (Murdza et al., 2022). Additionally, the presence of a liquid-like layer on crack surfaces is thought to further enhance the healing process (Murdza et al., 2022). Independent surface-scale observations further indicate that healing in ice is not purely time-driven, but governed by thermally activated transport processes (Demmenie et al., 2022).

In their model for sea-ice, Dansereau et al. (2016) adopted a time-driven healing with an imposed constant rate. However, the healing through sintering is reported to happen during short periods as a result of impact load during collision of ice particle (Szabo and Schneebeli, 2007; Bahaloo et al., 2022). Moreover, the healing rate is reported to be affected by temperature and pressure (Schulson et al., 2016). Motivated by these observations, we put forward a new model for healing of ice whereby the energy absorbed into the viscous mechanism is assumed to be deriving the healing. The energy dissipated as heat through the viscous processes can be regarded as a localized heat source enhancing the molecular mobility at the crack interface, and accelerating surface diffusion of water molecules and promoting the formation of a thicker liquid-like layer, both of which contribute to enhanced healing (Murdza et al., 2022). The proposed mechanism is similar to the viscous sintering observed in amorphous solids such as glass and magma (Scherer and Garino, 1985; Vasseur et al., 2013). We propose that the rate of healing is proportional to the viscous energy release, as expressed by:

where is the viscous strain rate and Eh is an additional model constant representing the internal characteristic energy required for healing. Being expressed in terms of the viscous energy, the healing rate naturally inherits its pressure and temperature dependency.

Including healing into the damage mechanics, however, is not straightforward, since the damage yield function, together with the consistency requirement (Eq. 14), fully describes the evolution of the damage level, and hence, the healing cannot be introduced into the yield function. Within the framework of damage mechanics, the issue is handled by introducing two distinct state variables for damage and healing, whose combined effect is included in the free energy potential. This strategy seems to be less relevant for ice since damage and healing seem to have similar and opposite effects that should be described by a single state variable, as proposed by Dansereau et al. (2016). Herein, we sidestep the issue by activating the healing process, described by Eq. (19), only when the state of the damaged material is below the yield limit, i.e. f<0, and assume that the damage evolution given by Eq. (14) describes the combined effect damage and healing. Therefore, when f<0 the elasticity formulation will be replaced with

with the second term describing the increase in stress due to a decrease in the damage level as a result of healing described by Eq. (19). It can be easily shown that the Maxwell system will be thermodynamically admissible and energy creation is prevented as long as the characteristic healing energy is greater than the undamaged elastic energy, i.e. Y<Eh. Naturally, the healing process is only activated when D>0.

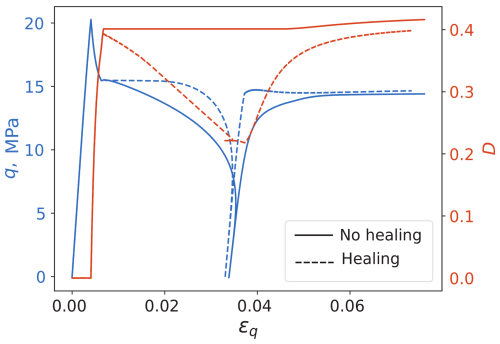

The effect of the proposed healing mechanism is demonstrated in Fig. 9 which presents the deviatoric stress-strain response and the damage evolution, with and without healing mechanism, in a triaxial test under conditions similar to those for Fig. 8, with and an arbitrarily chosen value of Eh=5 MPa for the healing process. The loading involves an initial constant strain rate of followed by gradually decreasing and reversing the strain rate until q=0, and reloading with gradually increasing strain rate to its initial value. During the unloading stage and stress relaxation, the state of the material falls below the yield function (f<0) which activates the healing mechanism. The energy stored in the elastic component is gradually transferred to the viscous component, a portion of which will reverse the damage through the viscous healing process described by Eq. (19). Figure 9 shows that, when healing is activated, the damage level (dashed line) starts to decrease during the unloading stage until almost half of the damage incurred during the first loading stage is recovered. Upon reloading, the damage level starts to rise again approaching the eventual value achieved by the simulation without healing (solid line). When healing is present, the associated stress-stress response during the unloading-reloading cycle exhibits a higher stiffness, which can be attributed to the recovery of the elastic stiffness. This higher stiffness induced by healing qualitatively resembles the response reported in loading/unloading tests on ice (see Kenny, 1992).

Experimental data targeting the healing of ice at the macroscopic scale within the framework of damage mechanics is indeed scarce. Therefore, while the formulation of healing given in Eq. (19) appears to capture qualitatively the basics of the healing process, its quantitative performance and its natural dependence on parameters such as pressure and temperature remain to be verified. Further exploration of these effects is left to future studies. Nevertheless, the present formulation offers an appropriate first step toward incorporating healing into constitutive models of ice. Including such mechanisms is essential for accurately capturing long-term mechanical behavior of ice where damage reversal can significantly influence strength, stiffness, and structural integrity.

The formulation developed in this study relies on simplifying assumptions that naturally limit its applicability. It assumes isotropy, while elasticity, creep, and damage in polycrystalline ice depend on crystallographic fabric and on the alignment of microcracks, which can produce direction-dependent stiffness and flow (Alley, 1988; Azuma, 1995; Pralong et al., 2006). More importantly, accuracy of prediction is also expected to decline near the pressure melting point because additional thermally activated mechanisms, including grain boundary processes and recrystallization or enhanced mobile dislocation activity, can lead to faster than Arrhenius creep (Morgan, 1991; Cole, 2020). Moreover, microstructural and compositional influences such as salinity and brine content, porosity, and grain size and its evolution are not represented even though they can modify effective stiffness and the operative creep mechanisms in natural ice (Langleben and Pounder, 1963; Goldsby and Kohlstedt, 2001). The adopted Maxwell configuration does not capture the primary creep phase, which is commonly attributed to partially recoverable deformation and evolving internal stress fields rather than viscous flow (Duval et al., 2010). The proposed viscosity-driven healing mechanism remains yet to be verified and uncalibrated. The triaxial behavior has been compared only at relatively high mean stress levels, on the order of 10 MPa, due to the limited availability of experimental data. These stress magnitudes are particularly relevant as they are comparable to basal overburden pressures typically encountered beneath glaciers (Herman et al., 2015, 2021; Cook et al., 2020).

From an experimental perspective, dedicated experiments can significantly help determine which rheological framework (Maxwell, Kelvin, Burgers, etc.) most closely represents ice behavior. Moreover, although the viscous-driven healing process proposed here is physically appealing, it remains unverified by experiments. Targeted experiments, particularly load-hold-reload and low-frequency cyclic triaxial tests conducted under controlled confinement and temperature, are essential to confirm the potential correlation between strain rate and stiffness recovery. Addressing these challenges will further enhance the model's applicability to a wide range of cryospheric, glaciological, and geotechnical engineering problems, especially those involving long-term loading, cyclic deformation, or evolving thermal regimes.

This study presented a comprehensive three-dimensional constitutive model for ice, developed to capture the intricate and interdependent effects of temperature, pressure, and strain rate, referred to as the thermobarokinetics of ice. Building upon the Maxwell elasto-brittle framework of Dansereau et al. (2016), the proposed model introduces several key enhancements that address critical limitations in existing approaches. As a central contribution is the adoption of a unified Arrhenius-type expression for temperature and pressure dependence of both the viscosity and the damage initiation threshold, which allows the model to reproduce the interdependence of thermal, mechanical, and kinetic effects using a minimal and physically meaningful set of parameters.

The model was calibrated and tested against independent datasets from triaxial compression experiments on polycrystalline ice. Validation results confirmed the model's ability to replicate a broad spectrum of observed behaviors. The model plausibly reproduces the stress–strain response of ice, including the transition from ductile to brittle failure as a function of strain rate and confining pressure, and captures both peak and residual stress magnitudes with relatively good accuracy in line with experimental observations. The model also reflects the suppressive role of high confining pressure on damage development, as well as the sensitivity of ice strength and ductility to temperature. Moreover, its predictions for stress relaxation align closely with available time-dependent experimental data, further reinforcing its credibility.

A physically motivated formulation for healing was also proposed, inspired by viscous sintering processes observed in amorphous materials such as glass. This mechanism ties the rate of healing to the rate of viscous energy dissipation, thereby embedding pressure and temperature sensitivity into the recovery process. Preliminary simulations indicate a progressive restoration of stiffness during relaxation, offering a promising path forward for modeling long-term behavior and damage recovery in ice.

The experimental data used in this study were obtained from previously published sources. The model code is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

F. S.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. M. P.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. M. R.: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Rachel Glade (University of Rochester) and Dr. Véronique Dansereau (ISTerre-IGE, France) for the engaging and insightful discussions, which significantly helped the development of this work.

This research has been supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Networks of Centres of Excellence of Canada (grant nos. RGPIN-2020-06480 and ALLRP-2023-590791 held by M. Pouragha and Discovery Grant held by M. Rayhani).

This paper was edited by Mahya Roustaei and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Alaei, E., Marks, B., and Einav, I.: A hydrodynamic-plastic formulation for modelling sand using a minimal set of parameters, J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 151, 104388, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmps.2021.104388, 2021. a

Alley, R. B.: Fabrics in polar ice sheets: development and prediction, Science, 240, 493–495, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.240.4851.493, 1988. a

Azuma, N.: A flow law for anisotropic ice and its application to ice sheets, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 128, 601–614, https://doi.org/10.1016/0012-821x(94)90173-2, 1994. a

Azuma, N.: A flow law for anisotropic polycrystalline ice under uniaxial compressive deformation, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol., 23, 137–147, https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-232X(94)00011-L, 1995. a

Bahaloo, H., Eidevåg, T., Gren, P., Casselgren, J., Forsberg, F., Abrahamsson, P., and Sjödahl, M.: Ice sintering: Dependence of sintering force on temperature, load, duration, and particle size, J. Appl. Phys., 131, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0073824, 2022. a

Balendran, B. and Nemat-Nasser, S.: Double sliding model for cyclic deformation of granular materials, including dilatancy effects, J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 41, 573–612, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5096(93)90049-l, 1993. a

Barnes, P., Tabor, D., and Walker, J.: The friction and creep of polycrystalline ice, Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences, 324, 127–155, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1971.0132, 1971. a

Barrette, P. D. and Jordaan, I. J.: Compressive behaviour of confined polycrystalline ice, Distributed through the NRC Centre of Ice-Structure Interaction, Canadian Hydraulic Centre, https://doi.org/10.4224/12340921, 2001. a

Barrette, P. D. and Jordaan, I. J.: Pressure–temperature effects on the compressive behavior of laboratory-grown and iceberg ice, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol., 36, 25–36, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-232x(02)00077-0, 2003. a

Blackford, J. R.: Sintering and microstructure of ice: a review, J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys., 40, R355, https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/40/21/r02, 2007. a

Brodeau, L., Rampal, P., Ólason, E., and Dansereau, V.: Implementation of a brittle sea ice rheology in an Eulerian, finite-difference, C-grid modeling framework: impact on the simulated deformation of sea ice in the Arctic, Geosci. Model Dev., 17, 6051–6082, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-17-6051-2024, 2024. a

Chaboche, J.: Continuum damage mechanics: Present state and future trends, Eng. Fract. Mech., 105, 19–33, https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-5493(87)90225-1, 1987. a, b

Cole, D.: On the physical basis for the creep of ice: the high temperature regime, J. Glaciol., 66, 401–414, https://doi.org/10.1017/jog.2020.15, 2020. a, b

Cole, D. M.: A model for the anelastic straining of saline ice subjected to cyclic loading, Philos. Mag. A, 72, 231–248, https://doi.org/10.1080/01418619508239592, 1995. a

Cole, D. M.: Modeling the cyclic loading response of sea ice, Int. J. Solids Struct., 35, 4067–4075, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7683(97)00301-6, 1998. a

Cook, S. J., Swift, D. A., Kirkbride, M. P., Knight, P. G., and Waller, R. I.: The empirical basis for modelling glacial erosion rates, Nat. commun., 11, 759, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14583-8, 2020. a

Dansereau, V., Weiss, J., Saramito, P., and Lattes, P.: A Maxwell elasto-brittle rheology for sea ice modelling, The Cryosphere, 10, 1339–1359, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-10-1339-2016, 2016. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h

Dansereau, V., Weiss, J., Saramito, P., Lattes, P., and Coche, E.: Ice bridges and ridges in the Maxwell-EB sea ice rheology, The Cryosphere, 11, 2033–2058, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-11-2033-2017, 2017. a

Demmenie, M., Kolpakov, P., Nagata, Y., Woutersen, S., and Bonn, D.: Scratch-healing behavior of ice by local sublimation and condensation, J. Phys. Chem. C, 126, 2179–2183, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.1c09590.s001, 2022. a

Derradji-Aouat, A.: A unified failure envelope for isotropic fresh water ice and iceberg ice, in: Proceedings of ETCE/OMAE joint conference energy for the new millenium, https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=6a7637d6-4d6a-49c5-af9f-54a651b61e65 (last access: 4 July 2025), 2000. a, b, c

Derradji-Aouat, A.: Multi-surface failure criterion for saline ice in the brittle regime, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol., 36, 47–70, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-232x(02)00093-9, 2003. a

Duddu, R. and Waisman, H.: A temperature dependent creep damage model for polycrystalline ice, Mech. Mater., 46, 23–41, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmat.2011.11.007, 2012. a

Durham, W., Heard, H., and Kirby, S. H.: Experimental deformation of polycrystalline H2O ice at high pressure and low temperature: Preliminary results, J. Geophys. Res.-Sol. Ea., 88, B377–B392, https://doi.org/10.1029/jb088is01p0b377, 1983. a, b

Duval, P., Montagnat, M., Grennerat, F., Weiss, J., Meyssonnier, J., and Philip, A.: Creep and plasticity of glacier ice: a material science perspective, J. Glaciol., 56, 1059–1068, 2010. a

Fish, A. M.: Combined Creep and Yield Model of Ice under Multiaxial Stress, in: Proceedings of the 2nd International Offshore and Polar Engineering Conference, ISOPE–I–92–205, San Francisco, California, USA, 1992. a

Gagnon, R. and Gammon, P.: Triaxial experiments on iceberg and glacier ice, J. Glaciol., 41, 528–540, https://doi.org/10.3189/S0022143000034869, 1995. a, b, c, d, e

Glen, J. W.: The creep of polycrystalline ice, P. Roy. Soc. A. Math. Phy., 228, 519–538, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1955.0066, 1955. a, b, c, d, e

Goldsby, D. and Kohlstedt, D. L.: Superplastic deformation of ice: Experimental observations, J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth, 106, 11017–11030, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000JB900336, 2001. a

Gratz, E. and Schulson, E.: Brittle failure of columnar saline ice under triaxial compression, J. Geophys. Res.-Sol. Ea., 102, 5091–5107, https://doi.org/10.1029/96JB03738, 1997. a

Herman, A.: Granular effects in sea ice rheology in the marginal ice zone, Philos. T. Roy. Soc. A, 380, 20210260, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2021.0260, 2022. a

Herman, F., Beyssac, O., Brughelli, M., Lane, S. N., Leprince, S., Adatte, T., Lin, J. Y., Avouac, J.-P., and Cox, S. C.: Erosion by an Alpine glacier, Science, 350, 193–195, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab2386, 2015. a

Herman, F., De Doncker, F., Delaney, I., Prasicek, G., and Koppes, M.: The impact of glaciers on mountain erosion, Nat. Rev. Earth Environ., 2, 422–435, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-021-00165-9, 2021. a

Hutter, K.: Fundamental Glaciology: Modeling Thermomechanical Processes of Ice in the Geophysical Environment, Engineering and Materials Sciences, International Glaciological Society, Cambridge, UK, ISBN 9780946417988, https://doi.org/10.1017/jog.2021.69, 2020. a

Jones, S. J.: The confined compressive strength of polycrystalline ice, J. Glaciol., 28, 171–178, https://doi.org/10.3189/s0022143000011874, 1982. a, b, c, d, e, f

Jones, S. J. and Chew, H. A.: Creep of ice as a function of hydrostatic pressure, J. Phys. Chem., 87, 4064–4066, https://doi.org/10.1021/j100244a013, 1983. a, b

Jordaan, I. J., Matskevitch, D. G., and Meglis, I. L.: Disintegration of ice under fast compressive loading, Int. J. Fract., 97, 279–300, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018605517923, 1999. a

Kalifa, P., Ouillon, G., and Duval, P.: Microcracking and the failure of polycrystalline ice under triaxial compression, J. Glaciol., 38, 65–76, https://doi.org/10.3189/s0022143000009606, 1992. a, b

Karr, D. G. and Choi, K.: A three-dimensional constitutive damage model for polycrystalline ice, Mech. Mater., 8, 55–66, https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-6636(89)90005-7, 1989. a

Kenny, S. P.: The influence of damage on the creep behaviour of ice subject to multiaxial compressive stress states, Master's thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14783/11042 (last access: 4 July 2025), 1992. a, b

Langleben, M. P. and Pounder, E. R.: Elastic parameters of sea ice, Ice and snow; properties, processes, and applications: proceedingsof a conference held at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 12–16 February 1962, 69–78 pp., Cambridge, Mass, M.I.T. Press, 1963. a

Lemaitre, J. and Chaboche, J.-L.: Mechanics of solid materials, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521328530, 1994. a

Marigo, J.-J.: Étude numérique de l'endommagement, EDF – Bulletin de la Direction des Études et Recherches, Série C: Mathématiques, Informatique, pp. 27–48, ISSN 0013-4511, 1982. a

Meglis, I., Melanson, P., and Jordaan, I.: Microstructural change in ice: II. Creep behavior under triaxial stress conditions, J. Glaciol., 45, 438–448, https://doi.org/10.3189/s0022143000001295, 1999. a, b

Mellor, M. and Cole, D. M.: Deformation and failure of ice under constant stress or constant strain-rate, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol., 5, 201–219, https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-232x(82)90015-5, 1982. a

Miao, S., Wang, M. L., and Schreyer, H. L.: Constitutive models for healing of materials with application to compaction of crushed rock salt, J. Eng. Mech., 121, 1122–1129, https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-9062(96)85045-5, 1995. a

Michel, B.: A mechanical model of creep of polycrystalline ice, Can. Geotech. J., 15, 155–170, https://doi.org/10.1139/t78-016, 1978. a

Mizuno, Y.: Effect of hydrostatic confining pressure on the failure mode and compressive strength of polycrystalline ice, J. Phys. Chem. B, 102, 376–381, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp963163b, 1998. a, b

Morgan, V.: High-temperature ice creep tests, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol., 19, 295–300, https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-232x(91)90044-h, 1991. a

Murdza, A., Schulson, E. M., Renshaw, C. E., and Polojärvi, A.: Rapid healing of thermal cracks in ice, Geophys. Res. Lett., 49, e2022GL099771, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022gl099771, 2022. a, b, c

Murrell, S. A. F., Sammonds, P. R., and Rist, M. A.: Strength and Failure Modes of Pure Ice and Multi-Year Sea Ice under Triaxial Loading, in: Ice-Structure Interaction: IUTAM/IAHR Symposium, St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada, 1989, pp. 339–361, Springer, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-84100-2_17, 1991. a, b, c

Nadreau, J.-P. and Michel, B.: Yield and failure envelope for ice under multiaxial compressive stresses, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol., 13, 75–82, https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-232x(86)90009-1, 1986. a

Nadreau, J. P., Nawwar, A. M., and Wang, Y. S.: Triaxial testing of freshwater ice at low confining pressures, J. Offshore Mech. Arct., 113, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.2919929, 1991. a

Nye, J. F.: The flow law of ice from measurements in glacier tunnels, laboratory experiments and the Jungfraufirn borehole experiment, P. Roy. Soc. A. Math. Phy., 219, 477–489, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1953.0161, 1953. a, b, c, d, e

Nye, J. F.: The distribution of stress and velocity in glaciers and ice-sheets, P. Roy. Soc. A. Math. Phy., 239, 113–133, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1957.0026, 1957. a, b

Olason, E., Boutin, G., Korosov, A., Rampal, P., Williams, T., Kimmritz, M., Dansereau, V., and Samaké, A.: A new brittle rheology and numerical framework for large-scale sea-ice models, J. Adv. Model. Earth Sy., 14, e2021MS002 685, https://doi.org/10.1002/essoar.10507977.2, 2022. a

Paterson, W.: Secondary and tertiary creep of glacier ice as measured by borehole closure rates, Rev. Geophys., 15, 47–55, https://doi.org/10.1029/rg015i001p00047, 1977. a, b

Pralong, A., Hutter, K., and Funk, M.: Anisotropic damage mechanics for viscoelastic ice, Continuum Mech. Thermodyn., 17, 387–408, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00161-005-0002-5, 2006. a

Ren, Y., Cai, F., Yang, Q., and Su, Z.: Contact-dependent inertial number and μ (I) rheology for dry rock-ice granular materials, Eng. Geol., p. 107995, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2025.107995, 2025. a

Rist, M. and Murrell, S.: Ice triaxial deformation and fracture, J. Glaciol., 40, 305–318, https://doi.org/10.3189/s0022143000007395, 1994. a, b, c, d, e, f

Sammonds, P., Murrell, S., and Rist, M.: Fracture of multiyear sea ice, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 103, 21795–21815, https://doi.org/10.1029/98JC01260, 1998. a

Schapery, R.: Models for the deformation behavior of viscoelastic media with distributed damage and their applicability to ice, in: Ice-Structure Interaction: IUTAM/IAHR Symposium, St. John’s, Newfoundland Canada, 1989, pp. 191–230, 1991. a

Scherer, G. W. and Garino, T.: Viscous sintering on a rigid substrate, J. Am. Ceram. Soc., 68, 216–220, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1151-2916.1985.tb15300.x, 1985. a

Schulson, E. M.: The brittle compressive fracture of ice, Acta Metall. Mater., 38, 1963–1976, https://doi.org/10.1016/0956-7151(90)90308-4, 1990. a

Schulson, E. M., Nodder, S. T., and Renshaw, C. E.: On the restoration of strength through stress-driven healing of faults in ice, Acta Mater., 117, 306–310, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2016.06.046, 2016. a

Simo, J. and Ju, J.: Strain- and stress-based continuum damage models—I. Formulation, Int. J. Solids. Struct., 23, 821–840, https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-7177(89)90117-9, 1987. a

Sinha, N. K.: Rheology of columnar-grained ice: Phenomenological viscoelasticity of columnar-grained ice has been experimentally investigated and analyzed in an effort to explain many apparent peculiarities of the deformation behavior of polycrystalline ice, Exp. Mech., 18, 464–470, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02324282, 1978. a

Sinha, N. K.: Elasticity of natural types of polycrystalline ice, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol., 17, 127–135, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-232x(89)80003-5, 1989. a, b

Sinha, N. K., Zhan, C., and Evgin, E.: Uniaxial Constant Compressive Stress Creep Tests on Sea Ice, J. Offshore Mech. Arct., 117, 283–289, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.2827235, 1995. a

Szabo, D. and Schneebeli, M.: Subsecond sintering of ice, Appl. Phys. Lett., 90, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2721391, 2007. a

Tremblay, L. B. and Mysak, L.: Modeling sea ice as a granular material, including the dilatancy effect, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 27, 2342–2360, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0485(1997)027<2342:msiaag>2.0.co;2, 1997. a

Treverrow, A., Budd, W. F., Jacka, T. H., and Warner, R. C.: The tertiary creep of polycrystalline ice: experimental evidence for stress-dependent levels of strain-rate enhancement, J. Glaciol., 58, 301–314, https://doi.org/10.3189/2012jog11j149, 2012. a, b

Vasseur, J., Wadsworth, F. B., Lavallée, Y., Hess, K.-U., and Dingwell, D. B.: Volcanic sintering: timescales of viscous densification and strength recovery, Geophys. Res. Lett., 40, 5658–5664, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013gl058105, 2013. a

Voitkovsky, K.: The relaxation of stresses in ice, in: Proc. International Conference on Low Temperature Science: Physics of Snow and Ice, Sapporo, Japan, vol. 1, pp. 329–337, 1967. a, b, c, d

Voyiadjis, G. Z. and Abed, F. H.: A coupled temperature and strain rate dependent yield function for dynamic deformations of bcc metals, Int. J. Plasticity, 22, 1398–1431, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijplas.2005.10.005, 2006. a

Weertman, J.: Creep deformation of ice, Annu. Rev. Earth Pl. Sci., 11, 215, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ea.11.050183.001243, 1983. a

Wilchinsky, A. V. and Feltham, D. L.: Anisotropic model for granulated sea ice dynamics, J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 54, 1147–1185, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmps.2005.12.006, 2006. a

Xiao, J. and Jordaan, I.: Application of damage mechanics to ice failure in compression, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol., 24, 305–322, https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-232x(95)00014-3, 1996. a, b

Xu, Y., Hu, Z., Ringsberg, J. W., and Chen, G.: Nonlinear viscoelastic-plastic material modelling for the behaviour of ice in ice-structure interactions, Ocean Eng., 173, 284–297, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2018.12.050, 2019. a

Zeitz, M., Levermann, A., and Winkelmann, R.: Sensitivity of ice loss to uncertainty in flow law parameters in an idealized one-dimensional geometry, The Cryosphere, 14, 3537–3550, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-14-3537-2020, 2020. a

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Mathematical notation

- Model formulation

- Model validation and parametric exploration

- Healing mechanism

- Limitations and future validation

- Conclusions

- Code and data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Mathematical notation

- Model formulation

- Model validation and parametric exploration

- Healing mechanism

- Limitations and future validation

- Conclusions

- Code and data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References