the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Review article: Weddell Sea Polynya formation, cessation and climatic impacts

Holly Ayres

Birte Gülk

Aditya Narayanan

Casimir de Lavergne

Malin Ödalen

Alessandro Silvano

Xingchi Wang

Margaret Lindeman

Nadine Steiger

Open-ocean polynyas, areas with little or no sea ice, reappeared extensively in 2016 and 2017 over the Maud Rise in the Weddell Sea after a 40-year hiatus, raising a series of unresolved questions about the atmosphere-ice-ocean interactions in the Antarctic region. These major polynyas significantly influence moisture and heat exchange between the atmosphere and the ocean, impacting both regional and global climate dynamics, as well as ecosystem functioning and biogeochemical processes. Notably, they may play a crucial role in contributing to the formation of Antarctic Bottom Water and influencing global ocean circulation. In this Review, we synthesize current knowledge on the drivers and impacts of Weddell Sea polynyas. Recent occurrences have been linked to factors such as a strengthening Weddell Gyre, a negative Southern Annular Mode, extreme local atmospheric conditions (atmospheric rivers and cyclones), and subsurface ocean heat buildup which acts as a preconditioning factor. The associated deep ocean convection from these polynyas can enhance air-sea gas exchange and trigger earlier phytoplankton blooms due to the influx of iron and nutrients from the deep ocean. While advancements in observation and modeling techniques have significantly improved our understanding of polynyas, substantial uncertainties remain regarding their interaction with recent Antarctic sea ice loss, their sensitivity to ocean mixing schemes, their excessive size or frequency in climate simulations, and future projections. Therefore, future research should focus on developing comprehensive four-dimensional regional observatories and targeted, data-constrained coupled models that accurately capture atmosphere-ice-ocean interactions across various timescales.

- Article

(7881 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Polynyas are traditionally described as open water areas within the sea ice pack (Smith et al., 1990; Smith and Barber, 2007). In reality, polynyas are rarely completely ice free, and rather covered by frazil ice or newly formed thin ice, especially in coastal regions during winter (Nakata et al., 2021). These features play a crucial role in polar climate, which is currently undergoing rapid changes. Spanning areas as large as hundreds of kilometers across, polynyas can persist from weeks to months, with some recurring at consistent locations over many years. The formation of a polynya opens up a direct pathway for atmosphere-ocean exchanges during winter, when they would otherwise be insulated by the sea ice cover. In the Southern Ocean, polynyas are significant drivers of sea ice formation and water mass transformations (Bennetts et al., 2024), which affect global ocean circulation and climate variability (SO-CHIC consortium et al., 2023). Broadly categorized into coastal and open-ocean types, their formation mechanisms and impacts differ significantly.

Coastal polynyas (Golledge et al., 2025), also known as “latent heat” polynyas, are primarily formed by katabatic winds (Comiso and Gordon, 1996; Tamura et al., 2008) or oceanic currents (Arbetter et al., 2004; Morales Maqueda et al., 2004). These forces move adjacent pack ice away from the coastline, facilitating the rapid formation of new ice and resulting in high rates of sea ice production in these regions. Coastal polynyas in Antarctica are key sites for the formation of the coldest and densest water mass, Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW), which overflows the continental shelves and spreads into the global abyss (Nihashi and Ohshima, 2015; Silvano et al., 2023). Many of these polynyas recur annually and are relatively predictable.

On the other hand, open-ocean polynyas, or “sensible heat” polynyas, emerge within the pack ice, away from coastal influences, and are typically generated by the convection of sensible heat from the upwelling of warmer ocean waters. Although rarer than their coastal counterparts, open-ocean polynyas have profound implications for ocean circulation and heat exchange between the ocean and the atmosphere (Rheinlænder et al., 2021; Kurtakoti et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2023). In the Southern Hemisphere, the most notable open-ocean polynya was the Weddell Sea Polynya (WSP) observed in the mid-1970s (Carsey, 1980). The Weddell Sea is bordered to the east by Coats Land (20° E) and to the west by the Antarctic Peninsula (60° W), thus stretching over a quarter of the circumpolar band. In 2016 and 2017, smaller polynyas opened within the same region, centered on the Maud Rise seamount (65° S, 2° E, red star in Fig. 1a) in the eastern Weddell Sea (Maud Rise Polynyas (MRPs); Comiso and Gordon, 1987; Cheon and Gordon, 2019; Campbell et al., 2019). This seamount rises from the abyssal plain at 5 km depth to about 1.8 km below the sea surface. Maud Rise is an important bathymetric feature of the Weddell Sea, which brings relatively warm water closer to the surface via interactions with ocean currents (Brandt et al., 2011; Swart et al., 2018). Small open-ocean polynyas also occur in the Cosmonaut Sea off Enderby Land (Comiso and Gordon, 1987, 1996; Gordon and Comiso, 1988; Arbetter et al., 2004; Qin et al., 2022), and in the Cooperation Sea (Qin et al., 2022).

Figure 1(A) Bathymetry of the Weddell Sea. The vectors are the surface geostrophic velocity, time-averaged from 2002 through 2018, derived from remotely observed dynamic ocean topography (Dragomir, 2023), showing the Weddell Gyre. The Maud Rise is marked with a red star. (B) Sea ice concentration from satellites averaged over September 2017, showing the Maud Rise Polynya. Contours show the time-averaged mean sea level pressure (Pa) from 2015 through 2018 as anomalies relative to the time-averaged mean sea level pressure from 2000 through 2023.

Major open-ocean polynyas may contribute to AABW formation, disrupting conventional flow pathways by creating dense water masses and releasing subsurface heat stored in the Southern Ocean (Gordon, 1991). When large, persistent WSPs formed during the 1970s (Fig. 2), deep convection affected the full water column down to 3000–4000 m depth (Gordon, 1978), with wide-ranging climate impacts, temporarily reducing ocean heat transport toward Antarctic glaciers (Wang et al., 2017), enhancing snowfall over the continent (Goosse et al., 2021), and altering deep water properties possibly as far north as the northern Pacific Ocean (Hirabara et al., 2012). However, climate models such as those used in phase 6 of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6) struggle to simulate realistic open-ocean polynyas (Mohrmann et al., 2021), so that their past and future frequency and impacts have been challenging to constrain.

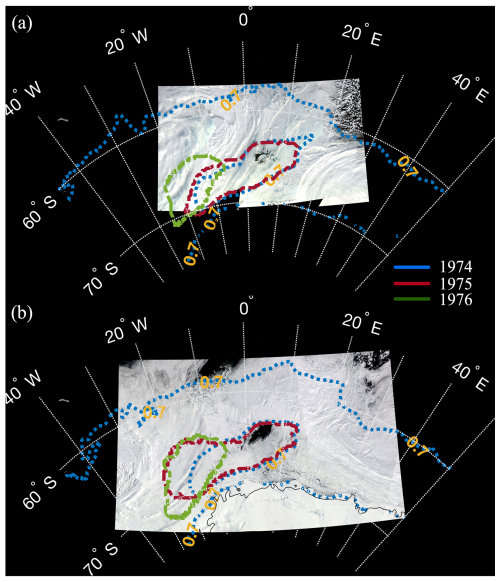

Figure 2Optical images at 500 m resolution from (a) MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) on 6 August 2016 and (b) VIIRS (Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite) on 25 September 2017, showing the polynya. The monthly 70 % sea ice concentration isolines for 1974 (blue), 1975 (red), and 1976 (green) retrieved from ESMR (Electrically Scanning Microwave Radiometer) are overlaid, representing the polynya area (threshold: 70 %). The isolines correspond to (a) August and (b) September.

Recent events, such as the re-emergence of polynyas in the Weddell Sea and the current unprecedented decline in Southern Ocean sea ice, have challenged our understanding of polynyas and their role in the Southern Hemisphere climate. They have also spurred significant progress through newly collected in situ observations, improved satellite products, and advances in modeling approaches. These tools provide fresh insights into the drivers and consequences of polynyas, making this an opportune moment to synthesize current knowledge. While coastal polynyas have been extensively studied in terms of their processes and broader connections (Jeong et al., 2023; Golledge et al., 2025), few studies have comprehensively addressed the critical processes in open-ocean polynyas, particularly those that may directly relate to recent abrupt changes in Antarctica (Purich and Doddridge, 2023). Notably, although the 2016 Maud Rise Polynya occurred during a period of declining sea ice, no similar polynya events were observed in 2022–2023 despite record-low sea-ice extent (Raphael and Handcock, 2022; Purich and Doddridge, 2023). This shows that polynya formation does not necessarily coincide with extreme events of sea ice retreat; specific atmospheric circulation patterns and oceanic preconditioning are likely essential for offshore polynya opening. As Southern Ocean sea ice is currently undergoing rapid changes (Sect. 2.1), and is projected to decline in the 21st century (Roach et al., 2020; Holmes et al., 2022; Raphael et al., 2025), there is a clear need to deepen our understanding of open-ocean polynyas in the Weddell Sea and their links to sea ice evolution.

In this Review, we synthesize current knowledge of the drivers and impacts of these phenomena. We begin with an overview of historical Weddell Sea polynyas from early satellite observations and paleoclimate records (Sect. 2.2). In Sect. 3 we discuss the oceanic and atmospheric processes that lead to polynya formation and their interactions with biogeochemistry and sea ice dynamics. In Sect. 4 the connections between polynyas and atmosphere-ocean feedbacks are discussed. In Sect. 5, we explore the uncertainties in the knowledge of polynyas today and impacts of climate change on future polynya dynamics. Finally, we conclude by summarizing key advances and remaining challenges for understanding the dynamics and importance of open-ocean polynyas in the Weddell Sea (Sect. 6).

2.1 Antarctic sea ice: current changes

Polynyas are inherently linked to sea ice cover, which influences Earth's albedo and modifies the exchange of heat, freshwater, momentum and gases between the atmosphere and ocean. The formation of open-ocean polynyas is influenced by regional scale sea ice conditions, particularly in the Ross, Amundsen, and Weddell seas (Liu et al., 2023).

Since 1979, Antarctic sea ice concentration (SIC) has been closely monitored by satellites. Between 1979 and 2014, an increasing trend was observed in the Antarctic sea ice extent (SIE: the total area of sea ice coverage with a SIC greater than 15 %) (Comiso et al., 2017; Parkinson, 2019), with varying regional trends. However, a record minimum SIE was observed on 21 February 2023, about 1.05 × 106 km2 below the 1981–2010 average (Purich and Doddridge, 2023; Liu et al., 2023), and 136 000 km2 below the previous record low reached on 25 February 2022 (Raphael and Handcock, 2022). The record minimum follows a sharp decline in SIE and SIC in 2016 (Purich and Doddridge, 2023). The sustained negative sea ice area anomalies since 2016 indicate a possible transition to a negative trend (Clem et al., 2022), akin to what is already evident in the Arctic, and consistent with global warming.

Processes involved in circumpolar sea ice loss also favor conditions that enable polynya formation. The Weddell Sea has notably experienced a significant decline in SIE since 2016 (Turner et al., 2020; Abram et al., 2025). This decline is attributed to factors such as a positive El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), an enhanced Zonal Wave Number 3 pattern (Stuecker et al., 2017; Schlosser et al., 2018; Stammerjohn et al., 2021), and the unprecedented occurrence of severe storms and atmospheric rivers (Meehl et al., 2019). The reduction was also accompanied by the reopening of the polynya near the Maud Rise in 2016 and 2017 (Fig. 1b), with each of these events being significantly larger than any since the 1970s extreme events (Turner et al., 2020) (Fig. 2). The sea ice loss can cause a robust weakening of the tropospheric westerly jet and favor the negative phase of the Southern Annular Mode (SAM) (Ayres and Screen, 2019). The further decline in sea ice in 2022 and 2023, especially in the Bellingshausen Sea region, highlights the impact of regional warming and atmospheric and oceanic drivers on SIE (Zhang et al., 2022; Purich and Doddridge, 2023; Clem et al., 2022; Gilbert and Holmes, 2024).

In addition to SIC, sea ice thickness is also used to identify polynyas, especially coastal polynyas. However, unlike SIE, there is an absence of comprehensive, long-term records of sea ice thickness across Antarctica to detect polynyas and explore the sea ice processes surrounding WSP and MRP occurrences in particular. Despite the technical challenges involved in measuring sea ice thickness and volume, recent satellite observations have identified instances of notable thinning of sea ice up to three months ahead of the opening of Maud Rise polynyas in 2016–2017 (Zhou et al., 2022).

Numerical models augment satellite observations as a valuable tool for analyzing Antarctic sea ice variability. The ensemble mean among historical simulations from CMIP6 models is close to Antarctic SIE observations, especially since most CMIP6 models can simulate multi-year ice in the Weddell Sea (Li et al., 2021). However, these global climate models overestimate Antarctic sea ice loss and variability over 1979–2018 (Roach et al., 2020). Moreover, many CMIP6 models simulate unrealistically frequent open-ocean polynyas in the Southern Ocean (Mohrmann et al., 2021), although there has been slight improvement over the previous CMIP phase.

2.2 Historical analysis of the polynyas in the Weddell Sea

The most dramatic observation of an open-ocean polynya occurred during the winters of 1974 to 1976 when a large opening with a maximum spatial extent of 350 000 km2 (Zwally and Gloersen, 1977) was detected from a passive microwave satellite within the ice pack of the eastern Weddell Sea (Fig. 2). It initially appeared near the Maud Rise seamount and persisted throughout the three consecutive winters (Carsey, 1980). Gordon and Comiso (1988) summarized that the WSP occupied the northeastern flank of Maud Rise in 1974 and extended into the northwest flanks in 1975, while the polynya quickly drifted southwestward into the Weddell Sea in 1976 (Carsey, 1980). Studies have shown that MRPs can be a precursor for WSP occurrence (Gordon, 1978; Martinson et al., 1981; Dufour et al., 2017; Kurtakoti et al., 2018; Cheon and Gordon, 2019). MRPs occur more frequently but irregularly and the largest and most recent openings occurred in the winter seasons of 2016 and 2017. The opening in July–August 2016 lasted for 21 d and reached an open-water area of 33 000 km2, while the opening in September 2017 lasted 1.5 months and expanded to 50 000 km2 (Campbell et al., 2019). Sea ice properties of the 2016 and 2017 MRPs were observed by the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer 2 (AMSR2) satellite (Melsheimer and Spreen, 2019), while oceanic measurements within the 2017 polynya were limited to observations from one Argo float (Campbell et al., 2019). Unlike the WSP in the 1970s, which propagated westward from Maud Rise at an average velocity of 0.013 m s−1 deduced from satellite images (Carsey, 1980), recent MRPs remained in the vicinity of Maud Rise. Furthermore, whereas the observed WSP existed from the beginning of the freezing season (Carsey, 1980), MRPs typically occur later in the season, near the end of winter, just before the retreat of the sea ice edge.

Although the specific impact of a large open-ocean polynya on paleoclimate records (e.g., ice cores) is not well known, some of these records likely have a signal related to open-ocean polynya formation. For example, the WSP of the mid-1970s is estimated to have caused an annual mean warming of almost 1 °C in coastal regions, and an additional snow accumulation averaged over the sector of about 10 Gt yr−1 on the continent, at least in the sector between roughly 50° W and 0° E (Goosse et al., 2021). Goosse et al. (2021), therefore, used ice core records to reconstruct the occurrence of polynyas. They found that large open-ocean polynyas, such as those observed in the 1970s, are rare events, occurring at most a few times per century, and typically lasting only a few years without clear periodicity. However, it is important to note that these results are limited by the proxies used, such as oxygen isotopes, which are influenced by precipitation in specific locations and are unlikely to capture the occurrence of smaller polynyas. Although these findings remain somewhat ambiguous (Goosse et al., 2021), they underscore the potential for further reconstructions of past polynya activity using other paleoclimate proxies.

Open-ocean polynya formation is thought to be associated with large-scale atmospheric changes, although it remains unclear whether these changes are a cause or a consequence of polynya events. In particular, the SAM was in its negative phase before the observed WSP event and has been linked to open-ocean polynya occurrence (Gordon et al., 2007; Cheon et al., 2015; Campbell et al., 2019; Kaufman et al., 2020). Reconstructions of the SAM (Abram et al., 2014; Dätwyler et al., 2018) over the last millennium might thus indicate a relatively high probability of polynya occurrence during 1350–1400 and 1600–1650. Similarly, long-term variations in the rate of AABW formation could be partly linked to WSP frequency (Broecker et al., 1999), and it has been suggested that decreased open-ocean polynya activity might have slowed AABW production over the 20th century (Broecker et al., 1999).

3.1 Oceanic processes

The Weddell Sea is characterized by a seasonal pycnocline, formed by surface warming and sea ice melting in summer, and a permanent pycnocline that ensures vertical stability of the water column (Klocker et al., 2023). From April to June, the seasonal pycnocline disappears due to heat loss to the cold atmosphere and brine rejection (Fig. 3), and the permanent pycnocline shoals and weak (Martinson et al., 1981). The permanent pycnocline separates cold and fresh surface waters from warmer and saltier deep waters, often referred to as Warm Deep Water (WDW). During winter, the salinity difference between surface waters and WDW (i.e., the halocline) controls the resistance to deep convection across the Weddell Sea (Martinson et al., 1981).

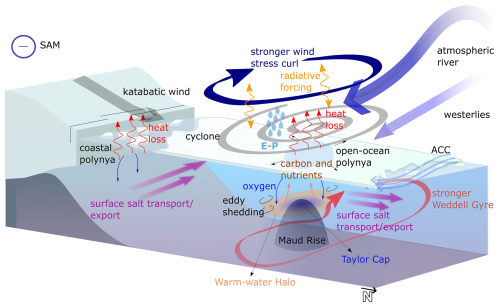

Figure 3Schematic view of the atmosphere, sea ice, ocean and biogeochemical processes during the MRP occurrence.

The winter halocline, or permanent pycnocline, is key to polynya formation and maintenance. To generate and maintain a polynya, the subsurface heat of WDW must be continuously brought to the surface by vertical mixing (Morales Maqueda et al., 2004). This upward heat transport can erode the pycnocline (Martinson and Iannuzzi, 1998), which is facilitated by both surface forcing and internal circulation processes. In examining polynya mechanisms, we differentiate between immediate short-term triggers (days to weeks before a polynya) versus long-term processes (active over months to years before a polynya). The long-term processes gradually erode the stratification of the water column, creating conditions that are favorable for polynya formation, referred to as “preconditioning”. Drawing from previous polynya studies based on observations, process-oriented models and Earth System Models (ESMs), we will discuss the roles of WDW inflow, flow-topography interactions, and surface forcing in the formation of WSPs and MRPs.

The properties of WDW within the Weddell Sea are influenced by water mass transformation within the region (Narayanan et al., 2023; Jullion et al., 2014), variations in the inflowing water masses (Gülk et al., 2023), and changes in the inflow's strength (Ryan et al., 2016). The WDW around Maud Rise plays a crucial role in preconditioning a polynya, with its properties significantly modulated by the eastern limb of the Weddell Gyre, which traverses the Maud Rise (Leach et al., 2011). The Weddell Gyre variability consequently affects the stratification and the amount of heat contained in the subsurface ocean (Fig. 4). This variability occurs on both seasonal and interannual timescales. Seasonally, the gyre weakens during winter as expanding sea ice diminishes ocean surface stresses (Neme et al., 2021). On interannual timescales, variations in the Weddell Sea Low, a region of low pressure located east of Maud Rise, influence the cyclonicity of winds in the eastern Weddell Sea (Fig. 3). A deeper Weddell Sea Low enhances Weddell Gyre circulation (Cheon and Gordon, 2019) and directly impacts the eastern limb of the gyre (Fahrbach et al., 2004; Gordon et al., 2007). This gyre spinup enables the shoaling of the pycnocline, bringing the warm and saline WDW layer closer to the mixed layer. This proximity facilitates greater mixing of salt into the mixed layer, eroding the stratification in the years preceding a polynya event (Campbell et al., 2019).

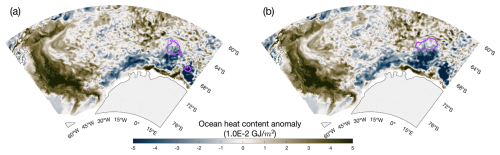

Figure 4CMEMS monthly upper ocean (0–300 m) heat content anomaly (deviation from the 1993–2023) during 2016 and 2017 in (a) August and (b) September. The purple isolines are the polynya detection based on 70 % sea ice concentration threshold.

The impingement of the Weddell Gyre on Maud Rise creates a local dynamical system, where a Taylor Cap is situated atop the Maud Rise and a warm-water Halo wraps around the northern half of Maud Rise (Gordon and Huber, 1990; Muench et al., 2001; De Steur et al., 2007). The warm-water Halo is distinguished by a relatively warm subsurface layer with maximum temperature exceeding 1 °C, lying below a notably shallow surface mixed layer. In contrast, the Taylor Cap exhibits relatively cold subsurface temperature and a deep mixed layer, accompanied by the least stable stratification in Maud Rise (Shaw and Stanton, 2014). A circulation is observed in the Halo, characterized by a strong surface-intensified jet with westward velocities exceeding 0.1 m s−1, accompanied by an eastward retroflection current to the south of this jet (Cisewski et al., 2011). Due to its isolation from the Gyre's flow, the Taylor Cap functions as a temporary local reservoir of heat and salt.

Large scale changes in the Weddell Gyre circulation also affect stratification locally around Maud Rise. These processes encompass flow-topography interactions, as well as surface and internal forcing. For example, flow-topography interactions generate eddies on the Maud Rise flank, which favor upwelling of warm subsurface water into the mixed layer, providing the necessary heat to melt the sea ice (Cheon and Gordon, 2019). Additionally, the local shedding of eddies (Fig. 3) can lead to a divergent Ekman stress that forces the sea ice apart (Holland, 2001) and moves water masses from the flanks to the center of the seamount. Because the flushing timescale over the dynamically isolated seamount far exceeds the flushing timescales over the more rapidly flowing flanks, this allows for the buildup of heat and salt anomalies over the Taylor Cap, as observed in the years 2015 through 2018 (Gülk et al., 2023; Narayanan et al., 2024). However, persistent enhanced vertical mixing and weak stratification in the subsurface may prevent the buildup of the heat reservoir via continuous, gradual heat flow toward the surface, potentially inhibiting MRP formation (Dufour et al., 2017). The surface forcing, such as storms (Fig. 3), can generate turbulence at the base of the mixed layer, enhancing vertical mixing (Campbell et al., 2019). In terms of internal forcing, observations reveal intrusions between the Taylor Cap and northern flank of Maud Rise, characterized by water mass interleaving (Mohrmann et al., 2022). These intrusions suggest lateral and vertical mixing along and across sloping isopycnals, transporting the flank WDW to the mixed layer base and subsurface layer over Maud Rise. Within this area, the structure of cold surface water overlying WDW, combined with great pressure and temperature gradients along the isopycnals, facilitates thermobaric effects, leading to convective plumes penetrating the warm deep layer. These plumes, in turn, cause the warm deep water to ascend, eroding the mixed layer and destabilizing the surface layer, potentially triggering abrupt deep convection (Akitomo, 2006; McPhee, 2000; Gülk et al., 2024). Moreover, these intrusions create conditions conducive to both types of double-diffusive instability (Akitomo, 2006; Mohrmann et al., 2022), further promoting the mixing of water masses.

With the onset of deep convection, heat from the subsurface layer is transferred to the mixed layer, leading to the melting of sea ice. Melting acts to restratify the water column, cutting off vertical mixing. This negative feedback (Martinson et al., 1981) hinders the formation of polynyas, even though the water column is very weakly stratified in most years over the Maud Rise. To sustain convection, an additional input of salt to the surface is necessary. For example, the 2016 and 2017 MRPs were initiated on the northern flank as Ekman advection transported additional salinity from the Taylor Cap to the northern flank between 2015 and 2018 (Narayanan et al., 2024). Deep convection events from preceding years also result in preconditioning by decreasing the vertical stability of the water column, making it more vulnerable to subsequent triggers (Campbell et al., 2019; Gülk et al., 2024).

Some of the observed processes were confirmed by the various modeling approaches of the scientific community. Typically, ESMs, ocean general circulation models (OGCMs) or reanalysis models are employed to investigate the polynya and its formation processes. Each modeling approach has its own set of limitations that should be borne in mind when interpreting the results. The scales of polynyas generated in ESMs generally far exceed those observed, yet ESMs still inform about theoretical ways of generating open-ocean polynyas (Latif et al., 2013). Some global OGCMs are able to represent the WSP on reasonable scales (Cheon et al., 2015), but MRPs are hardly reproduced and atmospheric feedbacks are absent in such models.

The likelihood of a polynya opening at Maud Rise is determined by the “preconditioning” that the water column can undergo on various timescales ranging up to multiple decades. Coupled ocean-atmosphere models indicate a periodic buildup of heat below the pycnocline in the Southern Ocean on multidecadal timescales preceding polynyas (Kurtakoti et al., 2018; van Westen and Dijkstra, 2020; Martin et al., 2013). Once preconditioned, the polynya and the associated deep convection can be triggered and sustained by the advection of surface salinity anomalies (Galbraith et al., 2011; Kurtakoti et al., 2018; Narayanan et al., 2024).

In ESMs, the formation of the larger WSPs is often preceded by the occurrence of MRPs and is favored by preconditioning on multidecadal timescales. WSPs that far outgrow MRPs require a spin-up of the Weddell Gyre (Kurtakoti et al., 2018). The opening of the WSP is maintained by the accumulated heat in the Weddell Gyre (Dufour et al., 2017; Martin et al., 2013; Rheinlænder et al., 2021). Besides the heat accumulation, a negative SAM favors the formation of WSPs by conferring a saltier surface ocean through a drier atmosphere (Cheon et al., 2015). A negative SAM results in a saltier surface in the Weddell Sea, and under certain circumstances, the smaller MRP can be advected westward by the Weddell Gyre to form a WSP.

Building on the similarities between observational and modeling studies, a roadmap to polynya formation can be created. The first stage is a weakening of the local stratification at Maud Rise via long-term preconditioning processes. Then, the onset of near-term mixing processes leads to catastrophic deep mixing bringing the heat from depth to the surface (Fig. 3), resulting in the opening of the sea ice pack. Occasionally a brief opening is observed in the first winter, as for example in 2016, which leaves the water column weakly stratified due to the associated deep mixing. In the following winter, reduced stratification increases the likelihood of another polynya opening, allowing processes such as the advection of surface salt anomalies to easily trigger deep convection. The re-occurrence of the polynya is determined by the remaining heat at depth, the SAM, and whether the weak stratification is replaced by a stronger one via the advection of more stratified water masses by the Weddell Gyre.

3.2 Atmospheric processes

Polynya formation is a coupled ocean-atmosphere process, with many studies suggesting various atmospheric triggers. Large-scale atmospheric variability, such as the SAM and Zonal Wave patterns, plays a foundational role in preconditioning the system, while localized processes such as cyclone activity and atmospheric rivers often act as immediate triggers.

3.2.1 Large-scale atmospheric variability

Polynya formation is closely linked to large-scale atmospheric patterns, particularly the SAM. A positive SAM phase is associated with stronger, poleward-shifted westerly winds, while a negative SAM is linked to weaker, equatorward-shifted winds. Gordon et al. (2007) theorized that a negative SAM, which brings colder and drier atmospheric conditions, reduces freshwater input to the surface ocean, increasing salinity and preconditioning the Weddell Sea for polynya formation. Conversely, a positive SAM enhances precipitation, freshening the surface and potentially hindering polynya expansion (Haumann et al., 2020).

The MRP events in 2016 and 2017 coincided with a persistently positive SAM. This phase introduced warmer and more humid air masses over the subpolar Weddell Sea, freshening the surface ocean and limiting the MRP's expansion. However, the strong cyclonic wind stress associated with the positive SAM promoted polynya preconditioning through pycnocline shoaling and salt injection into the mixed layer from below (see Sect. 3.1, Cheon et al., 2015; Campbell et al., 2019). Overall, the contrasting effects highlight that the SAM is a “double-edged” sword: positive phases promote WSP opening via momentum fluxes but hinder WSP formation via freshwater fluxes. A prolonged negative phase of SAM followed by a strong positive phase could be the perfect storm that favoured the mid-1970s WSP event: the negative phase preceding the event would have starved the surface Weddell Sea of freshwater (Gordon et al., 2007), while the SAM strengthening near the event could have promoted the onset of deep convection (Cheon et al., 2015).

The role of Zonal Wave (ZW) patterns adds another layer of complexity. These patterns describe large-scale atmospheric circulation structures, with ZW1, ZW2, and ZW3 referring to configurations with one, two, or three alternating high- and low-pressure centers encircling Antarctica. Positive phases of the SAM are typically associated with ZW1 or ZW2, which favor more zonal flow with limited meridional exchange. For example, a positive SAM index has been the norm since the 1980s, which is usually accompanied by a ZW1 or ZW2 pattern. However, in 2017, the Weddell Sea experienced an unusual ZW3 pattern alongside a strong positive SAM. This wave pattern is linked to increased meridional heat and moisture transport between the tropics and mid-latitudes (Raphael, 2004), intensifying cyclonic activity in the region and contributing to polynya formation.

3.2.2 Cyclonic activity and atmospheric rivers

Localized processes, particularly cyclone activity and atmospheric rivers (Francis et al., 2019, 2020), shown in Fig. 3, play a critical role in triggering polynya events. For example, the 2017 MRP highlights how cyclones can act as immediate drivers. Observational analysis highlights that in September 2017, the Weddell Sea experienced an unusually high frequency and intensity of cyclones, driven by a strong positive SAM (Francis et al., 2019) and an unusual ZW3 pattern. These cyclones, with category 11 (32.6 m s−1) Beaufort Scale winds, passed over Maud Rise, diverging the already thin ice in the region and creating conditions favorable for polynya formation at its peak in mid-September. Such atmospheric dynamics are consistent with findings from earlier studies that attribute cyclone activity to MRP preconditioning. Wang et al. (2019) analyzed a high-resolution, global ocean-sea ice model and found that record low atmospheric pressure systems over the Southern Ocean in 2016 reduced SIE, potentially setting the stage for the 2017 event. Similarly, Hirabara et al. (2012) used the Meteorological Research Institute Community Ocean Model (MRI.COM) and identified the key atmospheric processes linked to the WSP of the 1970s: (i) cyclonic wind stress anomalies in May and June induce a divergent sea ice drift anomaly, exposing more area to cool air and enhancing upward atmospheric surface turbulent heat flux; (ii) cold surface air in May and June was a prerequisite for deep convection, which was triggered by enhanced air cooling and positive surface salinity anomalies. These conditions set up a positive feedback loop that will support the formation of a WSP over the next few years.

Atmospheric rivers (Fig. 3), characterized by anomalously warm and moisture-laden air, further enabled the 2017 MRP and the 1973 WSP. These features increase downward longwave radiation, leading to enhanced ice thinning and melting (Francis et al., 2020). Such processes can combine with cyclonic wind stress anomalies inducing divergent sea ice drift, ultimately exposing open water to cooling and enhancing turbulent heat flux. Together with pre-existing positive surface salinity anomalies, these conditions can trigger deep convection and initiate a feedback loop that maintains polynya events (Hirabara et al., 2012).

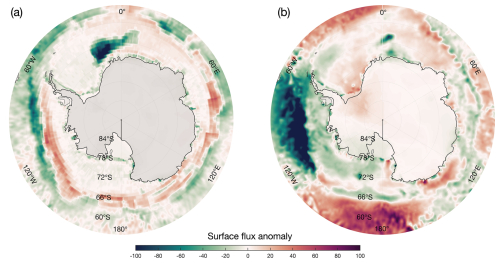

3.2.3 Atmospheric responses to polynya formation

Polynyas themselves influence atmospheric dynamics by releasing significant amounts of heat and moisture into the atmosphere. For example, Timmermann et al. (1999) proposed that the polynya would cause the warming of the low-level atmosphere. Using a thermal wind balance, assuming a level of non-motion at 6000 m height, they observed a resulting cyclonic wind field centered over the polynya leading to a divergence in sea ice. Dare and Atkinson (1999, 2000) conducted numerical studies with an atmosphere-only model, prescribing sea surface temperature (SST) and SIC to study the boundary layer and lower atmosphere's response to the polynya. Their findings suggest that heat released into the atmosphere enhances turbulent mixing in the boundary layer and increases downward momentum flux, resulting in stronger surface winds over the polynya. This process generates divergence and downdrafts upstream of the polynya, while convergence and updrafts occur downstream. With the development of better observations and models, Moore et al. (2002) used the NCEP-NCAR reanalysis to determine the atmospheric response to the 1970's WSP. These authors found that, when the WSP opens, it allows sizeable heat transfer from the ocean to the atmosphere during the cooler months, potentially affecting atmospheric dynamics. Specifically, they found an anomalous increase in air temperature up to 20 °C directly above the WSP, a 20 % increase in cloud cover, and turbulent heat fluxes exceeding 200 W m−2 (Fig. 5). These changes were accompanied by a significant reduction in sea level pressure by 6–8 hPa over the polynya, forming a regional dipole pressure pattern, with the western Weddell Sea exhibiting a smaller positive pressure. More recently, Ayres et al. (2024) conducted atmosphere-only simulations using atmospheric general circulation models (AGCMs) validated with ERA5 reanalysis to study the direct atmospheric response to the 1974 WSP. They found that the response to the polynya is highly localized, vertically confined to the boundary layer, and short-lived. Peak turbulent heat fluxes from the ocean to the atmosphere reached approximately 150 W m−2 (Fig. 5a), accompanied by surface air temperature increases of up to 7.5 K and warming extending as far as 100 km northeast of the polynya. Precipitation increased by ∼ 1 mm d−1 over the open water, and pressure decreased by up to 2 hPa. Observational analysis of the smaller MRP of 2016–2017 shows a turbulent heat flux through the ocean surface of much smaller magnitude (Fig. 5b), in the order of 40 W m−2 (Weijer et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2022).

3.3 Cryospheric processes

3.3.1 Sea ice thermodynamics

Once the polynya forms, sea ice is likely to refreeze due to the below-freezing air temperature, thus sea ice production is expected and can be approximately estimated through surface heat flux exchange. Ice production (Fig. 3) within coastal polynyas has been quantified using hydrographic profiles (Thompson et al., 2020), while satellite-based techniques are more commonly employed for this purpose (Drucker et al., 2011; Ohshima et al., 2016; Tamura et al., 2016). Coupled models, particularly those with high resolution, facilitate the simulation of their formation and maintenance (Marsland and Wolff, 2001) and enable the assessment of the relative contributions of various surface heat fluxes, including radiative, turbulent, and ocean heat (Wu et al., 2003). Similar methodologies apply to open-ocean polynyas, primarily using coupled (Timmermann et al., 1999; Walkington and Willmott, 2006) and/or high-resolution climate models (Weijer et al., 2017; Kaufman et al., 2020). However, direct quantification from observations of sea ice production in Southern Ocean open-ocean polynyas, such as the WSP or MRP, remains limited.

Zhou et al. (2023) made strides in this area by integrating satellite retrievals, in situ hydrographic observations, and data from the Japanese 55-year Reanalysis (JRA55) to investigate the sea ice energy budget and estimate sea ice production during the 2016–2017 MRP. They reported oceanic heat fluxes close to 36 and 31 W m−2 for the 2016 and 2017 polynyas, respectively, and noted that the 2017 open-ocean polynya generated nearly 200 km3 of new sea ice, rivaling the output of the largest Antarctic coastal polynyas.

3.3.2 Sea ice dynamics

In addition to the thermodynamic changes that affect sea ice in the WSP, the movement of sea ice plays a crucial role in the sea ice budget of the area. The movement of sea ice, characterized by either convergence into the polynya or divergence away from it, significantly impacts the net ice balance. Several studies compared the contributions of dynamic versus thermodynamic ice processes to sea ice area changes in the Weddell Sea (Holland and Kwok, 2012; von Albedyll et al., 2022). Holland and Kwok (2012), through a concentration budget analysis, determined that SIC over Maud Rise (named King Håkon Sea in their paper) during the freezing season is predominantly influenced by thermodynamic processes. Moreover, unlike coastal polynyas, which are primarily governed by latent heat fluxes and ice drift (Fig. 3), open-ocean polynyas like WSPs are more significantly affected by sensible heat fluxes, indicative of thermodynamic dominance (Kottmeier et al., 2003; Weijer et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2021).

The exact impact of dynamic processes on sea ice movement and distribution above Maud Rise cannot be fully determined without higher resolution sea ice drift data. Nonetheless, the findings from Zhou et al. (2023) align with previous studies (Holland and Kwok, 2012; von Albedyll et al., 2022) suggesting that dynamics play a lesser role (approximately 30 %) compared to thermodynamics. Consequently, the sea ice transiently produced within the polynya is likely to melt thermodynamically due to the influx of warm sub-thermocline waters. This competition between sea ice production and melting helps maintain the polynya, allowing it to undergo multiple cycles of partial melt and regrowth throughout its open period. While this melt-freeze cycle is likely essential for the maintenance of the polynya, it also limits the salinity of the convective chimney and thus the density of formed dense waters. This implies that open-ocean polynyas can ventilate the interior ocean without necessarily producing water masses as dense as traditional AABW. In sensible-heat-driven polynyas, suppressed ice growth reduces brine rejection, so the net densification can be weak even when deep convection occurs. This is in contrast to coastal polynyas where continuous sea-ice drift and brine rejection may allow more effective production of dense AABW (Silvano et al., 2023).

3.4 Biogeochemical processes

Sustained open-ocean polynyas are associated with deep convective mixing, which brings old deep waters into contact with the surface while injecting young ventilated waters into the ocean interior. Both effects have major implications for marine biogeochemistry: upwelling of deep waters brings remineralized carbon and nutrients to the surface, while downwelling of surface waters brings oxygen and preformed nutrients to the deep ocean. Notably, deep convective mixing does not have the same impact on ocean ventilation as gravity currents on the continental slope. Slope convection carries dense shelf waters down the continental slope to the abyssal ocean, but does not directly expose old deep waters to the surface. This distinction means that shelf and open-ocean modes of AABW formation do not have the same repercussions on marine biogeochemistry. Deep convective mixing such as that observed in the mid-1970s also transfers substantial amounts of heat from the deep ocean to the atmosphere (Gordon, 1978; Moore et al., 2002), affecting global deep ocean temperatures (Azaneu et al., 2013; Zanowski et al., 2015), regional stratification (Goosse and Zunz, 2014) and sea ice coverage (Zhang et al., 2019), all of which will ultimately impact air-sea gas exchange, nutrient distributions and marine ecosystems.

In situ observations collected in the aftermath of the 1970s WSP event revealed chimneys of anomalously high dissolved oxygen concentrations in the region reaching depths of 4000 m (Gordon, 1978; Foldvik et al., 1985), with concentrations >5.6 mL L−1 c.f. 5.0–5.4 mL L−1 in surrounding waters (Gordon, 1978). These observations unambiguously reveal the transfer of oxygen into deep layers of the subpolar Southern Ocean, including mid-depth layers that are customarily deprived of oxygen. Unfortunately, in situ observations from the 1970s do not allow to quantify the impact of Southern Ocean oxygenation at larger scale, nor do they provide information on nutrient and carbon fluxes associated with the WSP. Recently, Argo floats equipped with oxygen sensors profiled in the Maud Rise region; the measurements reveal high oxygen anomalies to about 1000 m depth (e.g., ±10 µmol kg−1 at ca. 650 m) following the opening of MRP in 2017 (Campbell et al., 2019), confirming the effectiveness of polynya events in ventilating deep waters.

Polynya impacts on ocean-atmosphere carbon exchange have been explored using a coupled climate model that simulates strong, intermittent deep convection events in the Weddell Sea (Bernardello et al., 2014). These model experiments show that each polynya event leads to substantial outgassing of natural remineralized carbon. Convection also leads to cooling of WDW (Gordon, 1978; Foldvik et al., 1985) which means this water can hold more preformed carbon. Thereby, ingassing of anthropogenic CO2 can also occur and can dominate over outgassing if atmospheric partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2) is sufficiently high (Bernardello et al., 2014). Depending on whether the outgassing of remineralized carbon or the subduction of preformed carbon dominates, the concentration of dissolved inorganic carbon in WDW will either decrease or increase. The change in dissolved inorganic carbon in WDW induced by the polynya will then change the lateral transport of carbon out of the Weddell Gyre, which normally is the component that leads to the gyre acting as a net sink of CO2 (MacGilchrist et al., 2019). Under a high-end anthropogenic climate change scenario, the model used by Bernardello et al. (2014) simulates a cessation of deep convection events, around the end of the 20th century (de Lavergne et al., 2014). This change in circulation and mixing tends to increase natural carbon storage (reduced outgassing of remineralized carbon) but also to reduce anthropogenic carbon uptake (reduced ingassing) over the 21st century, resulting in net weakening of cumulative ocean carbon uptake by 2100 (Bernardello et al., 2014). Hence, the impact of WSP events on ocean-atmosphere carbon partitioning depends on a subtle balance that evolves over time with atmospheric pCO2 and polynya frequency. In the model used by Bernardello et al. (2014), the cessation of Weddell Sea convection contributes respectively 5 % (−4.3 ± 1.9 PgC) and 18 % (−10.1 ± 3.9 PgC) of the global climate-induced reduction in total and anthropogenic ocean CO2 uptake, even though it only constitutes 1 % of the global ocean area.

Polynya-induced modifications to nutrient distributions (Fig. 3) can further alter the carbon cycle and its response to future change by affecting primary production and export. Phytoplankton growth in the Weddell Sea, as in the wider Southern Ocean, is primarily limited by the availability of light and iron (Bazzani et al., 2023). Manganese as a micronutrient has also been shown to play a co-limiting role in the Weddell Sea (Middag et al., 2011; Balaguer et al., 2023). Deep winter mixing supplies iron and other nutrients to the surface (Tagliabue et al., 2014; Arrigo, 2017), thus spring blooms are more likely to be limited by light, while iron limitation sets in later in the growing season (von Berg et al., 2020; Bazzani et al., 2023). Around the Maud Rise, chlorophyll (Chl-a) levels are ∼ 2–4 times higher than in the surrounding areas, with mean annual maximum levels (2002–2018) exceeding 2.7 mg m−3 (von Berg et al., 2020), likely due to topographically-induced mixing (Meredith et al., 2003; Prend et al., 2019). Here, iron-limited spring blooms have been reported (Bathmann et al., 1997; Croot et al., 2004; Geibert et al., 2010), although von Berg et al. (2020) argue that this is likely not the case during a polynya event with ongoing deep convection (Campbell et al., 2019) and associated iron supply. Hoppema and Anderson (2007) argue that the increased iron supply can sustain higher primary productivity in the region in polynya years c.f. non-polynya years. This could, in turn, offset some of the increase in surface pCO2 caused by upwelling of waters over-saturated in remineralized carbon.

Due to the rare occurrence of open-ocean polynya in this region, observational studies of their effect on ocean productivity are scarce. Phytoplankton bloom intensity, duration and timing in the MRP area were observed with autonomous biogeochemical floats for four years starting late 2014 (von Berg et al., 2020), thus covering the polynya years 2016–2017. While the bloom intensity in terms of column inventory of chlorophyll was not increased in polynya years, the onset of the bloom happened earlier in the year due to increased light availability. Satellite data confirm that this was associated with unprecedented surface levels of Chl-a for this time of year, reaching up to 4.7 mg m−3 during 2017 (Jena and Pillai, 2020). Meanwhile, von Berg et al. (2020) show that an early onset of the bloom leads to a prolonged growing season, allowing for a distinct iron-limited autumn season bloom that can only occur when the growing season is sufficiently long. von Berg et al. (2020) further demonstrate that a longer growing season allows for increased annual net community production by up to 100 % over Maud Rise, and thus suggest that the open-ocean polynya likely leads to enhanced carbon export to the ocean interior. However, they emphasize that similar behavior can be triggered by other processes causing early sea ice retreat in the region and is not unique to the polynya. By the same mechanisms, open-ocean polynyas are suggested to have contributed to biological carbon sequestration in the glacial ocean (Hu et al., 2023), and polynyas are suggested to have been a key environment for survival of phytoplankton species in glacial Antarctic waters (Thatje et al., 2008).

4.1 Atmosphere-ice-ocean interaction

The processes described in Sect. 3 and the many links between them indicate that the presence of polynyas significantly influences air-ice-ocean interactions. A clear understanding of these processes and interactions is crucial for determining the role of high latitudes in global climate regulation, particularly regarding deep ocean ventilation. For a long time, this has remained one of the major challenges facing contemporary polar research (Morales Maqueda et al., 2004).

Morales Maqueda et al. (2004) provided an initial comprehensive overview of polynya dynamics, ranging from observational insights to modeling approaches. The study further delved into their interactions with atmospheric and oceanic boundary layers, and their contributions to the surface heat, freshwater, and ice budgets. This included detailed analyses of in situ and remote sensing data on polynya locations and seasonality, as well as the atmospheric and oceanic conditions that foster their formation and maintenance. Studies reviewed in this work pointed towards an interplay between anomalous wind fields, heat and freshwater fluxes, sea ice divergence, and ocean flow interaction with local topography at Maud Rise in forming and sustaining the WSP (Parkinson, 1983; Timmermann et al., 1999; Marsland and Wolff, 2001; Muench et al., 2001; Holland, 2001). Despite the efforts of Morales Maqueda et al. (2004) and the numerous studies cited in their review, questions remained about the role of polynyas in shaping dense water production and air-sea heat fluxes that contribute to global ocean and atmospheric circulation patterns. Future climate change effects on polynyas, and thus on any atmosphere-ice-ocean processes influenced by their presence, were also unknown (see Sect. 5.2).

Recent studies using coupled models to observe the two-way interactions of the polynyas show that there may be links to distant climate, such as the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO) (Chang et al., 2020; Diao et al., 2022; Kaufman, 2022). However, these models have polynyas larger than those observed, which may lead to a greater heat flux to the atmosphere (Fig. 3), and therefore a stronger response (Moore et al., 2002). In their study of the atmospheric response to polynya, Ayres et al. (2024) noted that polynya occurrences not only affect the regional radiative heat balance, but also the local precipitation and cloud formation, albeit to a limited extent. On the other hand, climatic responses are not necessarily achieved solely through an atmospheric mechanism. Deep convective mixing and subsurface ocean cooling may trigger important changes in ocean circulation and hydrography. Some studies suggest an increase in AABW formation by open-ocean polynyas like the WSP of 1974-1976 (Gordon, 1978; Chang et al., 2020). Models and observations also indicate that the WSP causes transient cooling and freshening of the deep Southern Ocean and, with some lag, of the global ocean abyss (Azaneu et al., 2013; Zanowski et al., 2015). A minor component of the observed abyssal warming since the 1990s (Purkey and Johnson, 2010) may be linked to the recovery from the mid-1970s WSP events (Zanowski et al., 2015). The proposed mechanism is that the deep convective event associated with the WSPs injected an anomalously cold, dense water mass into the abyssal Southern Ocean. As this water gradually mixed, upwelled, and equilibrated over subsequent decades, it could have contributed to a delayed warming signal, consistent with deep ocean adjustment timescales in multi-century coupled model experiments (Zanowski et al., 2015; Zanowski and Hallberg, 2017).

Observational data on polynyas, particularly for the 1974–1976 WSPs, are notably scarce. Recent technical advances have significantly improved our ability to observe interactions within the polynya, especially with the wealth of data available on the 2016–2017 MRPs. For example, data from tagged marine seals (Treasure et al., 2017) and high-frequency profiling floats from the Argo program (Argo, 2024) or the SOCCOM (Southern Ocean Carbon and Climate Observations and Modeling) program (SOCCOM, 2019) provide valuable insights into vertical water stratification, as well as the structure of ocean fronts and cross-front mixing (Mohrmann, 2022). In addition, other observations have enabled detailed investigations into sea ice thickness – a key indicator of air-ice-ocean interactions – within polynyas using satellite technology. Notably, techniques such as L-band microwave radiometry from the Soil Moisture Ocean Salinity (SMOS) and Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) satellites allow for thickness measurements of thin sea ice in these regions (Mchedlishvili et al., 2022). The detailed observations acquired during the 2016–2017 MRP events will help to ground-truth the next generation of fully coupled atmosphere–ice–ocean general circulation models. Hirabara et al. (2012) highlighted the critical role of fully coupled atmosphere–ice–ocean general circulation models in more accurately simulating the formation processes of open-ocean polynyas. The advent of the latest high-resolution ESMs has opened new avenues for studying air-ice-ocean interactions within polynyas, as demonstrated by recent studies (Kaufman et al., 2020; Chang et al., 2020; Kurtakoti et al., 2018, 2021; van Westen and Dijkstra, 2020; Diao et al., 2022). For instance, Kaufman et al. (2020) employed statistical causal inference techniques within a high-resolution, fully coupled climate model to investigate how the MRP influences or reacts to climate variability. Their research established a clear link between polynya heat loss and various indicators of atmosphere–ocean variability in the high-latitude climate system.

4.2 Feedback

Both the WSP and MRP events illustrate the link between deep convection and interannual high-latitude climate variability. These events are influenced by both natural climate variability and human-induced trends, which affect ocean, ice, and atmospheric conditions that in turn control the formation of polynyas and deep convection in the Southern Ocean. For example, under preindustrial conditions, several climate model simulations exhibit natural oscillations in deep convection occurring from interdecadal (Galbraith et al., 2011; de Lavergne et al., 2014; Zanowski et al., 2015; Gnanadesikan et al., 2020) to centennial timescales (Martin et al., 2013; Latif et al., 2013; Cabré et al., 2017). Observed variations in WSP and MRP occurrences since the mid 1970s could be linked to internally generated or externally forced climate variability (Campbell et al., 2019). As an example, the 2016 MRP event has been linked to an anomalous deepening of the Amundsen Sea Low (Stuecker et al., 2017), itself caused by the combination of a strongly negative Southern Annular Mode and La Niña-like sea surface temperature anomalies in the tropics (Zhang et al., 2019). Deep convection in the open Southern Ocean could also drive internal variability in the ice-ocean-atmosphere system at high southern latitudes (Zhang et al., 2019). Indeed, it may be an important mechanism regulating the Southern Ocean heat balance on interannual to centennial timescales (Latif et al., 2013).

Feedback mechanisms and atmosphere-ocean-ice variability in the polynyas are evident in the preindustrial control simulation of the Energy Exascale Earth System Model (E3SMv0-HR). According to Kaufman et al. (2020), during polynya years, upward turbulent heat fluxes shift toward the poles, leading to increased ocean heat loss (Fig. 4) from the Weddell Sea, a reduction in the meridional temperature gradient, and an intensification of the cyclonic wind circulation in the Weddell Sea. This indicates that open-ocean polynyas in E3SMv0-HR can both influence and respond to atmospheric variability in the region. Another pre-industrial simulation, described by Chang et al. (2020) and based on the high-resolution (0.1° for the ocean and sea ice components) configuration of the Community Earth System Model version 1.3 (CESM1.3), showed the plausibility of multidecadal climate variability of WSPs, with occurrences approximately every 40–50 years. However, these WSP features are notably absent in low-resolution CESM simulations. Chang et al. (2020) also found that multidecadal variability of WSPs is not only closely correlated with an IPO-like pattern in sea surface temperatures but also precedes the IPO by about 4 years. This suggests interactions between Southern Ocean sea ice and tropical Pacific climate variability (England et al., 2020). While high-resolution climate simulations offer significant advantages, they are computationally demanding and energy consuming, making it challenging to link equilibrium climate sensitivity and polynyas from these simulations. Some challenges including the model resolution are further discussed in Sect. 6.

Interestingly, in NOAA's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL) CM2G coupled climate model, Zanowski and Hallberg (2017) found that when WSPs are forced regularly, it takes 18–25 years for Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW) volume transport anomalies to reach the South Atlantic, consistent with findings from the Norwegian Earth System Model (NorESM-OC1.2) under normal year forcing (Rheinlænder et al., 2021). In a 2000-year preindustrial control simulation from CM2G, it was shown that WSP recovery could account for 10 % ± 8 % of the recent warming in the abyssal Southern Ocean (Purkey and Johnson, 2010), with the strongest warming signals observed in the South Atlantic and Southern Ocean basins, diminishing with distance from the Weddell Sea (Zanowski et al., 2015).

Zhang et al. (2019) utilized a coupled ocean–atmosphere model which simulates multidecadal variability in Southern Ocean deep convection resembling the observed 1970s WSP. They demonstrated that the model can broadly reproduce observed trends in sea surface temperature and SIC over 1979–2012 when the model is initialized in an active phase of open-ocean convection. They suggested that the natural multidecadal variability of Southern Ocean deep convection could influence the detectability of surface temperature and sea ice responses to global warming. Echoing the findings of Zhang et al. (2019), Gjermundsen et al. (2021) analyzed 41 CMIP6 models and further discovered that those with strong Southern Ocean deep convection in their pre-industrial state tend to show greater warming at ocean depths but less surface warming under greenhouse gas forcing. This leads to a more negative short-wave cloud feedback. The analysis indicates that the feedback from marine boundary layer clouds and deep ocean warming are interconnected processes within a coupled system, which together account for a significant portion of the variation in effective climate sensitivity across different models (Gjermundsen et al., 2021).

5.1 Limitations in polynya knowledge

Despite substantial advances in observations, modeling, and theoretical understanding, open-ocean polynyas, particularly in the Weddell Sea, remain among the least understood components of the Southern Ocean climate system. Limitations persist across observational records, model parameterizations, and process representations, hindering our ability to predict their occurrence and assess their climate relevance.

The identification and characterization of polynyas in models and observations are themselves subject to uncertainty. In particular, the findings underscore how polynya detection is highly sensitive to the choice of sea ice metrics (SIC vs. SIT), and the temporal scale of analysis. Winter polynyas, for instance, may be masked in SIC fields due to rapid refreezing, whereas SIT thresholds can better capture low-ice regions that remain important for ocean convection. These differences complicate direct comparisons between satellite observations and model output, often leading to apparent inconsistencies in polynya detection and frequency. A coordinated use of both metrics – SIC and SIT – alongside improved model diagnostics will be essential for more robust future assessments.

Observational uncertainty is further exacerbated by the rarity and remoteness of large WSP events. While the 2016–2017 MRPs are relatively well-documented via reanalysis, satellite, and Argo float data, the 1970s WSP events remain sparsely observed, with little to no direct in situ information on vertical structure, mixing, or biogeochemical fluxes. This limits our ability to quantify key processes such as brine rejection, deep water formation, and heat flux partitioning, particularly during polynya onset and decay phases.

On the modeling side, CMIP-class models tend to produce either overly persistent or unrealistically large polynyas, or fail to simulate them at all. Differences stem from a wide range of factors including vertical mixing schemes, representation of eddies and dense water overflows, sea ice initial conditions, and parameterizations of air–sea–ice coupling (Heuzé et al., 2015; Mohrmann et al., 2021; Gülk et al., 2024). For example, coarse-resolution models often underestimate the restratification effect of mesoscale eddies, while high-resolution models that include eddy-resolving capability better maintain upper-ocean stratification and can produce more realistic, intermittent polynya events (Dufour et al., 2017). The sensitivity of WSP behavior to these factors has been confirmed by inter-model comparisons and perturbation experiments (Heuzé et al., 2015; Kjellsson et al., 2015; Gülk et al., 2024).

Furthermore, the potential biogeochemical impacts of WSPs remain underexplored. Few models include detailed representations of carbon or nutrient cycling within polynyas, and observational coverage of relevant fluxes (e.g., iron, dissolved inorganic carbon, alkalinity) is limited. As a result, the broader role of WSPs in Southern Ocean biogeochemistry and global carbon storage remains speculative, particularly under changing climate conditions.

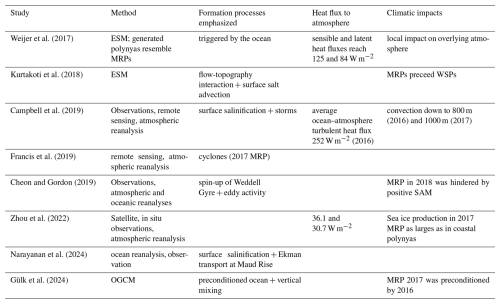

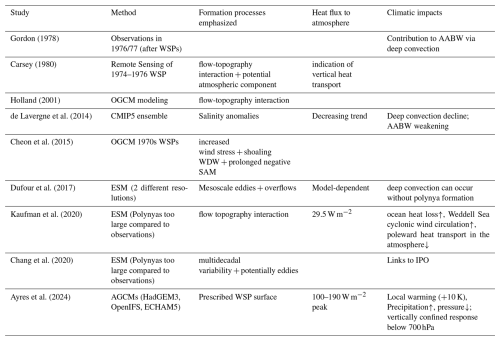

To clarify and compare key differences in formation, magnitude, and impacts across WSP and MRP studies, we provide a synthesis in Tables 1 and 2. The tables highlight observational versus modeled results across key metrics including formation mechanisms, ice production, heat fluxes, and broader climate feedback.

Gordon (1978)Carsey (1980)Holland (2001)de Lavergne et al. (2014)Cheon et al. (2015)Dufour et al. (2017)Kaufman et al. (2020)Chang et al. (2020)Ayres et al. (2024)Table 1Summary of key findings from major observational and modeling studies on Weddell Sea polynyas, highlighting agreement and divergence in polynya characteristics and impacts.

5.2 Polynya in the future

The past frequency of open-ocean polynya events in the Weddell Sea is largely unknown (Goosse et al., 2021). Forecasting the future frequency and magnitude of such events is thus a major challenge. Nonetheless, it is possible to outline the likely future changes in environmental conditions that favor or hinder polynya formation. Naturally, these changes depend on the future trajectory of greenhouse gas concentrations and the ensuing level of global warming. In addition, the transient century-scale response may differ from the longer term response (Yamamoto et al., 2015; Landrum et al., 2024). In the following discussion, we focus on climate projections over the 21st to 23rd centuries under high-end emissions scenarios.

The first key environmental factor to consider is the surface freshwater input at southern high latitudes. Climate models such as those participating in CMIP5 and CMIP6 indicate that precipitation over the high-latitude Southern Ocean has increased over recent decades and will likely continue to increase in the future (Fyfe et al., 2012). Additionally, future mass losses of the Antarctic ice sheet could deliver substantial additional freshwater to the Southern Ocean surface (Rignot et al., 2013). Hence, it may be expected that salinity stratification in the high-latitude Southern Ocean will intensify and thereby impede future open-ocean convection events (Noble et al., 2020). CMIP5 models that simulate open-ocean convection in the Southern Ocean provide support for this scenario: they predict a decline in convection over the 2000–2300 period under strong greenhouse forcing (de Lavergne et al., 2014). This decline occurs in all such CMIP5 projections despite their exclusion of ice sheet mass losses, and despite simulated changes in heat fluxes, sea ice and winds.

Other lines of reasoning could overturn this projected decline. First, it is possible that CMIP5 models overestimate sensitivity to freshwater fluxes due to biases in ocean circulation and mixing (Lockwood et al., 2021). For example, the weakness of Antarctic slope currents in such coarse models may lead to overestimated freshwater transport from Antarctic margins to the open Southern Ocean (Lockwood et al., 2021). Second, ESMs could underestimate the influence of future wind changes, due to poor representation of relevant processes such as mesoscale eddies or wind-driven mixing. As the SAM trends towards more positive under greenhouse forcing, atmospheric storms over the Weddell Sea may become stronger or more frequent, potentially contributing to destabilize the water column in the Maud Rise region (Campbell et al., 2019). In addition, a positive SAM will intensify negative wind stress curl and the gyre within the Weddell Sea (Lockwood et al., 2021), activating mesoscale eddies near Maud Rise and potentially promoting polynya events (Cheon and Gordon, 2019). Third, future changes in temperature stratification could overcome changes in salinity stratification (Rheinlænder et al., 2021; Beadling et al., 2022). For example, subsurface WDW in the Weddell Sea may warm in response to increasing meridional heat transport within an intensifying Weddell Gyre (Lockwood et al., 2021; Rheinlænder et al., 2021). Rapid build-up of the subsurface heat reservoir could ultimately favor stronger or more frequent convection events (Yamamoto et al., 2015; Martin et al., 2013).

Several modeling studies point to a potential future increase of open-ocean polynya events. By simulating surface wind stress, Antarctic meltwater, and their combined forcing in a pre-industrial control simulation with a global climate model and an ESM, Beadling et al. (2022) found the diminished sea ice cover, in combination with wind stress perturbation, enhances heat loss at high latitudes through enhanced upwelling of WDW and triggering of polynya events in the Weddell Sea. Similarly, Dias et al. (2021) showed that combining positive momentum, heat, and freshwater flux perturbations in the Australian Community Climate and Earth System Simulator Ocean Model (ACCESS-OM2) leads to significant sea ice reduction, expansion of the Ross and Weddell polynyas, and increased associated deep convection. These polynyas cease when the heat reservoir is depleted. A mixed scenario featuring a near-term increase in polynya activity followed by a decline is also a possibility (Landrum et al., 2024).

In essence, the future formation of open-ocean polynyas in the Weddell Sea or the wider Southern Ocean can be understood as a competition between opposing forces. On the one hand, there is the stabilizing influence of relatively fresh surface waters, influenced by surface freshening and thermodynamic effects linked to positive SAM and possibly increased ice sheet melting (de Lavergne et al., 2014; Bintanja et al., 2013). On the other hand, there are destabilizing factors such as the frequency of polar cyclones, the strength of the Weddell Sea gyre, and meridional heat transport, which can promote and trigger convection (Campbell et al., 2019; Yamamoto et al., 2015; Lockwood et al., 2021). Because ocean stratification in this region is controlled by a subtle balance of competing processes that are difficult to accurately model, the future of MRPs and WSPs in a warmer world remains highly uncertain.

-

Drivers of WSP and MRP formation and cessation. The WSPs are driven by the interplay between long-term oceanic preconditioning and short-term atmospheric forcing. Oceanic processes gradually erode the upper-ocean stratification above Maud Rise through the shoaling of WDW, driven by Weddell Gyre variability, mesoscale eddies, and flow-topography interactions. These mechanisms reduce vertical stability and increase the likelihood of deep convection. Atmospheric variability modulates and often triggers these oceanic conditions. On large scales, the SAM plays a dual role: negative SAM phases reduce freshwater input, increasing surface salinity and promoting destabilization, while positive phases enhance wind-driven mixing but counteract convection through increased precipitation and surface freshening. On shorter timescales, cyclones and atmospheric rivers act as immediate triggers by thinning sea ice, increasing ocean-atmosphere heat exchange, and initiating vertical mixing. These events are particularly potent when accompanied by unusual atmospheric patterns such as ZW3, which enhance moisture transport and storm activity over the Weddell Sea. Ultimately, the cessation of polynyas is governed by restratification through surface freshening and ice melt, which suppress further convection. The observed interplay of processes across spatial and temporal scales underscores the inherent complexity of WSP dynamics and the challenge of predicting their occurrence in a changing climate.

-

Atmosphere-ice-ocean interaction. WSPs significantly perturb the regional energy and mass balance by enabling direct ocean-atmosphere exchange in the otherwise ice-covered Southern Ocean. When open, these polynyas facilitate large upward turbulent heat fluxes (up to 150–200 W m2), leading to localized atmospheric warming, enhanced cloud formation, and increased precipitation directly over the polynya area. However, recent AGCM experiments and reanalysis data show that this response is localized in both space and time, largely confined to the boundary layer and fading quickly after polynya closure. In the ocean, WSPs enable deep convection that ventilates intermediate and abyssal layers, potentially contributing to AABW formation and influencing global ocean stratification and biogeochemistry. Model and observational studies also link WSPs to transient deep ocean cooling and freshening, with potential decadal-scale impacts. Although coupled model simulations have proposed teleconnections between WSPs and distant climate modes such as the IPO, such links remain uncertain and may be exaggerated by the unrealistically large polynyas simulated in some models. Overall, while WSPs exert a profound local influence on polar climate processes, their global impact depends strongly on event scale, duration, and coupling with the ocean and atmosphere.

-

Future projection. Projections of WSP activity remain deeply uncertain due to competing physical processes and modeling limitations. On the one hand, increased surface freshwater input from enhanced precipitation and Antarctic ice sheet melt is expected to strengthen upper-ocean stratification, thereby inhibiting deep convection and suppressing polynya formation. Indeed, most CMIP5 and CMIP6 models simulate a long-term decline in open-ocean convection under high-emission scenarios. However, alternative modeling studies suggest this decline may be overstated due to coarse resolution and underestimated roles of oceanic eddies, wind-driven mixing, and subsurface heat buildup. Trends toward a more positive SAM and intensified Weddell Gyre circulation could enhance wind stress curl and vertical mixing, promoting preconditioning near Maud Rise. In particular, subsurface warming of WDW through increased meridional heat transport may eventually destabilize the water column, potentially offsetting the stabilizing effects of freshening. Overall, the future trajectory of WSPs will be shaped by a delicate balance between enhanced surface stability and dynamic or thermodynamic destabilization, posing a significant challenge for reliable long-term projections.

-

Uncertainties and knowledge gaps. Although the observational and modeling efforts reviewed here address some key questions regarding WSPs and MRPs, many unknowns about polynya processes and simulations remain. For instance, recent studies have modeled polynyas larger than the largest observed in 1974 (Kaufman et al., 2020; Diao et al., 2022). This suggests caution in analyzing model polynya dynamics, as oversized polynyas may generate unrealistic coupled feedbacks and overestimate the role of coupled dynamics in polynya recurrence. As another example, Mohrmann et al. (2021) noted that half of the CMIP6 models they examined, particularly MPI-ESM1-2-(LR/HR), simulate extensive open-ocean polynyas in the Ross Sea, events that have not been observed in reality. Unrealistic winter polynyas can then lead to altered hydrography and unrealistically strong subpolar gyres in winter (Stoessel et al., 2015). Additionally, the presence of a WSP or MRP in models is highly sensitive to the specifics of ocean mixing schemes. Some modeling studies that do not use an initial sea ice fail to produce a WSP (Holland et al., 2014; Megann et al., 2014), but results can vary significantly between models due to differences in parameterizations, resolution, and initial conditions. For example, Kjellsson et al. (2015), Heuzé et al. (2015) and Gülk et al. (2024) altered numerical choices in the parameterization of vertical mixing and convection, freshwater forcing, and/or initial sea ice conditions, demonstrating that uncertainties in any of these factors can cause excessive deep convection or no convection at all in the open Southern Ocean. Their results imply that the presence of deep convection and offshore polynyas can only be controlled by considering all three factors simultaneously.

Our review highlights that no single process can be identified as the definitive trigger for Weddell Sea polynya formation. Instead, key drivers span different timescales: slow oceanic preconditioning via upper-ocean destratification unfolds over years to centuries, while atmospheric triggers such as cyclones or moisture intrusions operate on seasonal scales. Interactions across these different timescales and across the three media explain why open-ocean polynyas in the Southern Ocean are complex phenomena that continue to defy our theoretical, observational and modeling capacities.

The dynamic ocean topography dataset used in this study is available at https://doi.org/10.5258/SOTON/D3006 (Dragomir, 2023, 2024). Sea ice concentration data can be accessed from SSM/I-SSMIS Passive Microwave Data at https://doi.org/10.5067/MPYG15WAA4WX (DiGirolamo et al., 2022) and from Electrically Scanning Microwave Radiometer (ESMR) data at https://doi.org/10.5067/W2PKTWMTY0TP (Parkinson et al., 2004). Satellite imagery datasets include MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) 250 m resolution data from NASA's LAADS DAAC, available at https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MOD02QKM.061 (MODIS Characterization Support Team, 2017), and VIIRS (Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite) 750 m resolution data from NASA's MODAPS, accessible at https://doi.org/10.5067/VIIRS/VNP03MOD_NRT.002 (VIIRS Calibration Support Team, 2022). ERA5 atmospheric data can be accessed via the Copernicus Climate Data Store at https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.adbb2d47 (Hersbach et al., 2023). The GLORYS12V1 oceanic reanalysis (CMEMS) data is available through the Copernicus Marine Service at https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00021 (Copernicus Marine Service, 2023).

LZ, HA, BG, AN, CL and MÖ designed the study and wrote the manuscript. LZ, AN, and MÖ performed the data analysis. All authors wrote different parts of the text, provided insights regarding the interpretation of data and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This study received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No. 821001 (SO-CHIC). This research was supported by the Veni ENW research programme (project number VI.Veni.242.161), funded in part by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) under grant: https://doi.org/10.61686/FIJUT94740

This research has been supported by the Horizon 2020 (grant no. 821001), the Veni ENW research programme (project number VI.Veni.242.161), funded in part by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) under grant: https://doi.org/10.61686/FIJUT94740, the Ocean Cryosphere Exchanges in ANtarctica: Impacts on Climate and the Earth system, OCEAN ICE, which is funded by the European Union, Horizon Europe Funding Programme for research and innovation under grant agreement Nr. 101060452, https://doi.org/10.3030/101060452. Aditya Narayanan acknowledges funding from the NERC DeCAdeS project (grant no. NE/T012714/1). Alessandro Silvano acknowledges funding from NERC (grant no.NE/V014285/1).

This paper was edited by Petra Heil and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Abram, N. J., Mulvaney, R., Vimeux, F., Phipps, S. J., Turner, J., and England, M. H.: Evolution of the Southern Annular Mode during the past millennium, Nature Climate Change, 4, 564–569, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2235, 2014. a

Abram, N. J., Purich, A., England, M. H., McCormack, F. S., Strugnell, J. M., Bergstrom, D. M., Vance, T. R., Stål, T., Wienecke, B., Heil, P., Doddridge, E. W., Sallée, J.-B., Williams, T. J., Reading, A. M., Mackintosh, A., Reese, R., Winkelmann, R., Klose, A. K., Boyd, P. W., Chown, S. L., and Robinson, S. A.: Emerging evidence of abrupt changes in the Antarctic environment, Nature, 644, 621–633, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09349-5, 2025. a

Akitomo, K.: Thermobaric deep convection, baroclinic instability, and their roles in vertical heat transport around Maud Rise in the Weddell Sea, Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 111, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JC003284, 2006. a, b

Arbetter, T. E., Lynch, A. H., and Bailey, D. A.: Relationship between synoptic forcing and polynya formation in the Cosmonaut Sea: 1. Polynya climatology, Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 109, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003JC001837, 2004. a, b

Argo: Argo float data and metadata from Global Data Assembly Centre (Argo GDAC), SEANOE [data set], https://doi.org/10.17882/42182, 2024. a