the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Brief communication: Tropical glaciers on Puncak Jaya (Irian Jaya/West Papua, Indonesia) close to extinction

Thomas Mölg

Christian Sommer

The majority of glaciers have been retreating for many decades on a global scale due to anthropogenic climate change, including the mostly small glaciers in the Tropics. In this brief report, we document area changes of the Puncak Jaya glaciers in South-East Asia on West Papua, Indonesia, until the present. The survey was based on recent high resolution multispectral satellite imagery of PlanetScope and Pléiades missions from 2023 and 2024. Additionally, we digitized and georeferenced historical glacier extents from analogue maps, resulting in a new overview map of glacier change on Puncak Jaya since 1850. The results show a decrease of total glacier surface area by more than 99 % since 1850 and by ∼ 65 % since the last survey in 2018. In 2024, glacier area was 0.165 km2 ± 5 %. The development of Puncak Jaya glaciers is thus in line with the global shrinkage of (tropical) glaciers. Assuming the current area retreat rates to continue, it is very likely that Puncak Jaya glaciers will disappear around 2030.

- Article

(4034 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(818 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Global air temperatures have risen due to anthropogenic climate change (World Meteorological Organization, 2022). While the global annual mean near-surface air temperature of 2022 climbed 1.15 °C above the 1850–1900 pre-industrial average, corresponding to a global warming rate of 0.2 ± 0.1 °C per decade, surface air temperatures in mountainous areas show an enhanced increase of 0.3 ± 0.2 °C per decade (Hock et al., 2022; World Meteorological Organization, 2022). Moreover, atmospheric warming varies by region. In South-East Asia, mean annual air temperatures already started to rise between 1870 and 1940 and were 0.46 °C above the 1961–1990 average in 2022 (Allison and Kruss, 1977; World Meteorological Organization, 2022). In Indonesia, where Puncak Jaya glaciers are located, mean daily maximum air temperatures increased by 0.18 °C per decade between 1983 and 2012 (Supari et al., 2017). Regardless of region, glaciers around the globe have been in a mode of mass loss for many decades and tropical glaciers are no exception, as shown in recent surveys of tropical Andean and East African glaciers (Hock et al., 2022; Hinzmann et al., 2024; Fox-Kemper et al., 2021; Turpo Cayo et al., 2022). Some tropical glaciers even ceased to exist, e.g. the Conejeras Glacier, Colombia, which disappeared between 2023 and 2024 (World Glacier Monitoring Service WGMS, 2024).

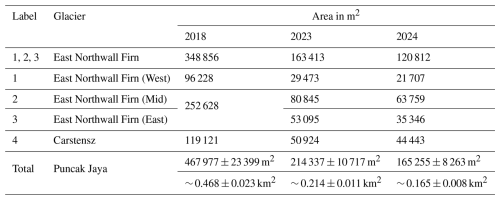

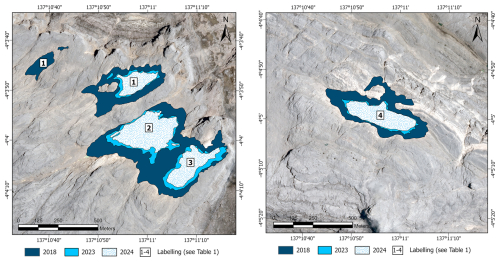

Figure 1The geographic setting of glaciers around Puncak Jaya. (a) Overview of glaciers and surrounding peaks (marked with red triangles) in the Puncak Jaya mountains. Puncak Jaya, with an altitude of 4884 m a.s.l., represents the highest peak in the region. East Northwall Firn Glacier is located close to (Gunung) Sumantri and Ngga Pulu peaks, while Carstensz Glacier lies next to Carstenz Timur peak. Glacier extents in the map are from 2005 (Openstreetmap Base map with contour lines (© OpenStreetMap contributors 2024. Distributed under the Open Data Commons Open Database License (ODbL) v1.0.), ESRI, NASA). (b) Glacier changes between ∼ 1850 to 2024, based on data of own surveys and of authors mentioned in Table S1 in the Supplement. Uncertainties and estimates in the extents of 1850 and 1972, discussed by Peterson and Peterson (1994), are sketched with dashed lines (Openstreetmap Base map with contour lines (© OpenStreetMap contributors 2024. Distributed under the Open Data Commons Open Database License (ODbL) v1.0.), ESRI). (c, d) Oblique photographs, taken during the 1936 and 1972 expeditions, showing glacial retreat especially of the Northwall Firn, indicated by a bifurcation in 1972, separating the Northwall Firn into an East and West part (Jean Jacques Dozy, 1936 as part of the expedition by Antonie Hendrikus Colijn, 1937 and Carstensz Glacier Expedition, 1972, Glacier Photograph Collection, National Snow and Ice Data Center, edited).

Glaciers at low altitude are termed “tropical” when the following criteria are fulfilled (Kaser and Osmaston, 2002). First, they must be located in the astronomic tropics between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn (23°26′13.3′′ N; 23°26′13.3′′ S); second, they must be located within the oscillation range of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ); third, the annual range of the air temperatures must be equal to, or smaller than, the daily temperature range. Currently, three areas fulfill these criteria. The Andes, where the majority of tropical glaciers is located, East Africa and New Guinea (Kaser and Osmaston, 2002). On New Guinea, glacier ice only exists in the West Papua region, formerly known as Irian Jaya region, located in the West of the New Guinea Highlands on the rugged Sudirman range around Puncak Jaya peak (4884 m a.s.l.) (Fig. 1a) (Permana et al., 2019). These glaciers are located in one of Earth's wettest regions (2500–4500 mm yr−1 precipitation), are strongly influenced by the El Niño Southern Oscillation and the South Pacific Convergence Zone and are the only remaining tropical glaciers in the West Pacific Warm Pool (Prentice and Hope, 2007; Permana et al., 2019).

Tropical glaciers are interesting from a scientific point of view in several ways, as their changes are influenced by local climatic drivers as well as by prominent modes of macro- and mesoscale climatic dynamics (e.g. Mölg et al., 2020, 2009). Moreover, their high-altitude location, often above 4000 m a.s.l. (Fig. 1a) and thus close to the 600 and 500 hPa levels in the atmosphere, makes them good indicators of global climatic changes in the mid troposphere (Allison and Kruss, 1977; Mölg et al., 2009). Therefore, glacier systems located in the tropical Andes and in East Africa have been examined extensively in the last decades, focusing on glacier area changes and global and local climatic factors influencing glacial retreat. Recent examples are e.g. Carrivick et al. (2024), Gorin et al. (2024), Hinzmann et al. (2024), Mölg et al. (2020), Turpo Cayo et al. (2022). However, the glaciers on Puncak Jaya have received less attention as the only extensive expeditions took place in 1973 and 2011 and the latest remote surveys were carried out between 2015 and 2018, creating a data gap to the present (Permana et al., 2019; Permana, 2011; Allison and Peterson, 1976). Thus, the present study aims to (i) close the existing data gap by examining the changes of glacier extent since the last surveys in 2015 and 2018 using high resolution multispectral satellite imagery, and (ii) construct a new map of glacial development from 1850 onwards by conducting a comprehensive data acquisition of (historical) analogue and digital data, which allows us to put the results of current glacier change into historical perspective.

During the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) large parts of New Guinea's high mountain areas were covered by ice and snow (Kaser and Osmaston, 2002; Brown, 1990). The total area covered was about 2000–2200 km2, including 863 km2 in the Puncak Jaya area (Hope and Peterson, 1976). After several glacier advances and retreats during the Greenlandian and Northgrippian stage of the Holocene, glaciers in the Puncak Jaya mountains began to retreat by the end of the Little Ice Age (LIA) between 1850 and 1875 (Allison and Kruss, 1977; Bowler et al., 1976; Prentice et al., 2011). Interestingly, the aforementioned glacier advances took place almost synchronously with neoglacial glacier advances on western Greenland and in the East African Rwenzori mountains (Bowler et al., 1976; Löffler, 1980; Peterson et al., 1973).

After the first report of glacier sightings in the Sudirman Range/Puncak Jaya mountains by the Dutch seafarer Jan Carstensz in 1623, the first expeditions to the glaciers did not take place until 1907 and 1909 (Wollaston, 1914; Temple, 1962; Hope, 1976). These expeditions were not able to reach the glaciers but documented their existence and extent through photography and cairns. After the first expedition that reached the glaciers in 1912, led by Alexander Frederick Richmond Wollaston and Abraham van de Water (Wollaston, 1914), the next expedition took place in 1936, led by Antonie Hendrikus Colijn and Jean Jacques Dozy, which successfully climbed the summits of Carstensz Timur and Ngga Pulu (Coljin, 1937; Dozy, 1938). Thereafter, further ethnographic and geologic expeditions took place (Le Roux, 1948; Dozy et al., 1939), followed by several reconnaissance flights conducted by the US military during World War II (Allison, 1974; Ballard, 2001). During these expeditions, cairns indicating glacial extent were erected, and photographs were taken that were of great value for understanding glacier change on Puncak Jaya (Fig. 1b, c, d).

The first ascent of Puncak Jaya mountain itself and the surrounding glaciers was accomplished by Heinrich Harrer in 1962 (Harrer, 1963; Hope, 1976). At this time, glacier retreat was already evident compared to the glacier extent in 1936 (Harrer, 1963). Between 1971 and 1973, a complete survey of all existing glacier areas on Puncak Jaya was conducted for the first time during two expeditions led by Australian researchers, finding the Southwall Hanging, Carstensz, Meren, East Northwall Firn and West Northwall Firn, Harrer, Wollaston and Van de Water glaciers (Fig. 1b, c, d) (Allison and Peterson, 1976). The survey results of these expeditions indicated a further significant decline of glacier area from 13 km2 in 1936 to 7.3 km2 in 1972 and 6.4 km2 in 1974 (Allison and Peterson, 1976).

From the 1970s onwards, satellite based remote sensing was increasingly used to measure glacier areas. SPOT satellite data, acquired in 1987, revealed a further reduction in total glacier area on Puncak Jaya to 5.09 km2 (Klein and Kincaid, 2006; Peterson and Peterson, 1994). Between 1997 and 2000 Meren Glacier disappeared (Prentice and Glidden, 2010; Klein and Kincaid, 2006). The next survey, conducted in 2006 by using a time series of high-resolution IKONOS satellite data from 2000 to 2005, found a further reduction in total glacier area to 2.15 km2 (Klein and Kincaid, 2006; Kincaid, 2007). During a survey in 2010, when ice core drilling was conducted on the glaciers to measure isotope composition, the disappearance of the last remnants of the Southwall Hanging Glacier was detected (Permana, 2011). The extents of the remaining glaciers East Northwall Firn and Carstensz were analysed again in 2018 using remote sensing imagery of PlanetScope mission, revealing a total surface area reduction from 0.653 km2 in 2015, 0.546 km2 in 2016 to 0.458 km2 in 2018 (Permana et al., 2019).

Due to the remote location and difficult access of Puncak Jaya glaciers, only few in-situ mass change and ice thickness surveys have been conducted, mostly covering short time periods: in 1972, negative mass balances of −57 × 103 m3 w.e. yr−1 with a surface lowering of 0.064 m yr−1 for the Carstensz Glacier and −989 × 103 m3 w.e. yr−1 with a surface lowering of 0.509 m yr−1 for the Meren/East Northwall Firn glacier were observed by the Carstensz Glacier Expedition (Allison, 1974). Maximum ice depth was estimated to be greater than 60 m for the East Northwall Firn Glacier, ∼ 85 m for Meren Glacier and ∼ 75 m for the Carstensz Glacier (Allison, 1974). Between 1995 and 1997, East Northwall Firn Glacier experienced a negative mass change of −4430 × 103 m3 w.e. yr−1, whereas between 1997 and 2000 a slightly positive mass change of 452 × 103 m3 w.e. yr−1 was surveyed (Prentice and Glidden, 2010). During an expedition in 2010, ablation stakes were placed on East Northwall Firn Glacier, revealing an annual ice thickness loss of ∼ 1.05 m (Permana, 2015). Ice thickness on East Northwall Firn Glacier further decreased from ∼ 30 m in 2010 to ∼ 20 m in 2016, while an estimated ice thickness of ∼ 6 m remained in 2022 (Permana et al., 2019; World Meteorological Organization, 2022). Although recent studies have not made statements about glacier velocity due to lack of data, the continuous area loss of the glaciers indicates that they can be considered relict ice.

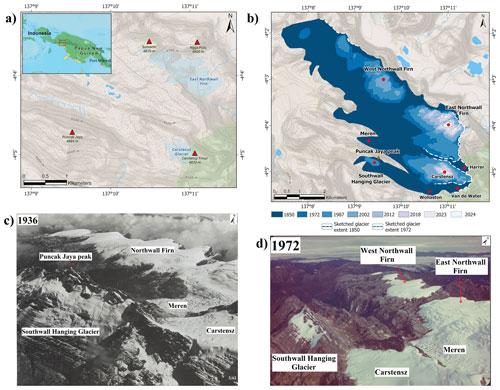

Figure 2Glacial retreat of East Northwall Firn Glacier (left) and Carstensz Glacier (right) between 2018 and 2024. Labels 1–4 on glacier areas refer to Table 1 (based on image data by © 2023, 2024 Planet Labs PBC and © CNES (2023), distribution Airbus DS, data provided by the European Space Agency. Background imagery of Pléiades mission provided by CNES, 2023). The original Pléiades image without annotations can be found in Fig. S1.

As the last surveys of 2015 and 2018 showed small glacier areas of < 0.2 km2 at Puncak Jaya, our study employed high resolution multispectral satellite imagery of PlanetScope mission (provided by Planet Labs PBC via the PlanetLabs Education and Research Programme) with a horizontal resolution of 3 m and a near-daily revisit capacity (Planet Labs PBC, 2023). Furthermore, very-high resolution multispectral satellite imagery of the Pléiades mission (provided by Airbus DS through the European Space Agency) with a horizontal resolution of 0.5 m and a daily revisit capacity was used to compensate for potential uncertainties (e.g. due to shading effects) in the lower resolution PlanetScope imagery (Airbus Defence and Space Intelligence, 2021). Although no distinct accumulation and ablation seasons exist at Puncak Jaya glacier area due to the homogenous inner-tropical climate setting, imagery selection focused on the time period from May to August when rainfall and relative humidity minima can be expected (Permana, 2011). However, some images from outside this season could also be considered (Table S2). Imagery selection focused on the absence of extensive cloud cover, shadowing, or fresh snowfall, which limited the number of available image acquisitions due to the high degree of cloud cover in the inner tropics and early morning cloud formation at Puncak Jaya (Prentice and Hope, 2007; Kaser and Osmaston, 2002). The selected images (Table S2), which were already provided orthorectified, color-corrected and -optimized, were loaded into Esri ArcGIS Pro (Version 3.1.3) software. A visual check of the orthorectification of the PlanetScope images was conducted by comparing several distinct landmarks using Sentinel 2 imagery (Table S3). As deviations were detected (Forward Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 0.76–3.60 m using 16 Control Points), georeferencing and image matching were applied using the Sentinel 2 image to increase the survey's accuracy.

Due to the size of remaining glaciers on Puncak Jaya, we delineated the glacier outlines manually based on visual inspection of all available high-resolution images using ArcGIS Pro, while using a scale range from 1:500 to 1:1200. Manual delineation/digitization of glacier outlines, executed by an analyst using cursor tracking, is less influenced by disturbing factors such as shading or debris cover, as it relies on the analyst's dynamic interpretation and visual verification. Despite the fact that this approach is typically more time-consuming than an automated survey (e.g. using band arithmetic methods), it is effective for small glacier areas with potential interferences, e.g. shading or snow cover, since visual validation is already included in the process (Hinzmann et al., 2024). As we used high-resolution multispectral imagery and did not detect snow cover, debris cover or shading issues, the ice areas were clearly distinguishable from surrounding rocky terrain and additional manual delineation runs were not necessary. However, to further increase the accuracy, we compared the results to very-high resolution Pléiades imagery and oblique photography from recent expeditions, whereby no deviations were detected. Previous works reported the range of uncertainty in glacier delineation to be between 2.3 % (Linsbauer et al., 2021), 3.3 % (Paul et al., 2020) and 5 % (Fountain et al., 2023). Hence, we assumed a maximum uncertainty of 5 % for our results, based on the findings of Paul et al. (2020, 2013). This approach was supported by a comparison between the results for total glacier area extent in 2018 by Permana et al. (2019) (0.458 ± 0.036 km2) and by our survey (0.468 ± 0.023 km2), resulting in a difference of ∼ 2.2 % between the point estimates (Table S1).

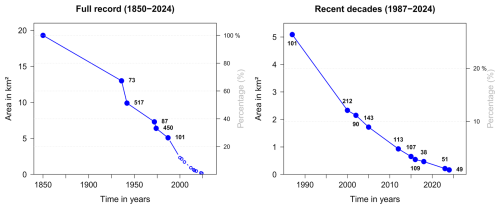

Figure 3Glacier area over time for all Puncak Jaya glaciers. The labels affixed to the data points correspond to the annual area loss rate (103 m2 yr−1) in the previous time range. The left panel provides an overview over the full record from 1850 to 2024, while the right panel zooms into the most recent decades. Left y axis represents total glacier area in km2 and right y axis represents the corresponding percentage.

In addition to the acquisition of present-day glacier area using satellite imagery, a new digital map with historical glacier extents dating back to 1850 was generated. This map was primarily based on the one published by Peterson and Peterson (1994), which was an updated version of a map created during the Carstensz Glacier Expedition in 1972, compiling survey results of historic glacier extents back to the 19th century (Anderson, 1976; Hope et al., 1976). As Peterson and Peterson (1994) and Kincaid (2007) reported glacier mapping errors in the original 1972 map, which were also noticable in our study with deviations of up to hundreds of meters, both analogue maps from 1972 and 1994, after being scanned on a flatbed scanner, were georeferenced in ArcGIS Pro, using a Sentinel 2 image (Table S3) with 12 control points in Affine Transformation. These control points based on survey points created for a local plane coordinate system with arbitrary datum during the 1972 Carstensz Glacier Expedition (Anderson, 1976) and were transformed to WGS84 UTM 53S coordinates using Helmert transformation for our use. However, these 12 control points present on the updated map by Peterson and Peterson (1994) were unevenly distributed. Thus, the total RMSE was ∼ 17 m, despite the addition of six control points based on geomorphological landmarks to account for the uneven distribution of control points. As the RMSE close to the glaciated areas was 3–7 m, and a visual inspection of a Sentinel 2 image (Table S3) to check for conformity with topographical characteristics supported the reliability of this result, the glacier areas for 1850, 1972 and 1987 were subsequently delineated manually and saved as polygon shapefiles. The glacier mapping errors in the 1972 map by Allison and Peterson (1976) left some data gaps in certain aspects of the mountain. These areas were sketched accordingly, following a combination of both maps by Allison and Peterson (1976) and Peterson and Peterson (1994) (Fig. 1b).

Furthermore, glacier contours were manually delineated for the years 2012, 2016 and 2018 based on RapidEye and PlanetScope data (Table S4), as the contemporaneous outlines by Permana et al. (2019) were not available. Glacier extents of 2002 were provided by the study of Klein and Kincaid (2006).

The trend of recession of Puncak Jaya glaciers since ∼ 1850, documented in previous publications (Allison and Peterson, 1976; Harrer, 1963; Permana et al., 2019; Klein and Kincaid, 2006; Kincaid, 2007), has continued to the most recent years. The total glaciated area shrunk from 19.3 km2 in 1850 to 6.4 km2 in 1974 and 2.15 km2 in 2002, and to 0.214 ± 0.011 km2 in 2023 and 0.165 ± 0.008 km2 in 2024 (Fig. 2, Tables 1 and S1). Between 2018 and 2024, the total glacier area shrunk by 0.303 ± 0.015 km2 or ∼ 65 %. The western part of the East Northwall Firn shows the smallest glaciated area with only ∼ 0.022 ± 0.001 km2 in 2024 and is likely to disappear first in the years ahead (Fig. 2).

Since the last survey in 2018, the westernmost part of the East Northwall Firn has disappeared and the main body of the East Northwall Firn has been separated into two parts by a bifurcation. All surveyed areas experienced area loss, while the East Northwall Firn experienced greater loss (0.228 km2) compared to the Carstensz Glacier (0.074 km2) from 2018 to 2024 (Fig. 2, Table 1), most likely due to the fact that the lost parts of the East Northwall Firn were located at a lower altitude than the Carstensz Glacier area.

By putting the current survey's results into perspective to historical changes of Puncak Jaya glaciated areas, the drastic decline becomes evident (Fig. 1b, Table S1). By 2002, the total glaciated area had declined by almost 90 % since 1850 (Klein and Kincaid, 2006) and in 2024 less than 1 % of the ∼ 1850 glacier surface area remains. The former Northwall Firn Glacier split into two parts at some time between 1942 and 1962, resulting in the West Northwall Firn and East Northwall Firn part (Allison and Peterson, 1976). Meren Glacier vanished between 1997 and 2000 (Klein and Kincaid, 2006), while West Northwall Firn and Southwall Hanging glaciers disappeared between 2005 and 2012 (Fig. 1b; Kincaid, 2007). Within the last two decades, the glaciers consisting of the remnants of East Northwall Firn and Carstensz glacier retreated to areas of the highest altitudes possible, close to the mountain tops of Carstensz Timur and Ngga Pulu.

The area loss rate shows a steady decline since ∼ 1850 and indicates no climatological time period of glacier growth within the last 170 years (Fig. 3). Despite a lack of data from the first half of the 20th century, a relatively steady retreat rate can be assumed for this period according to aerial photographies and cairn position surveys (Allison and Peterson, 1976). It can be noted that the loss rate slowed down between 2016 and 2024 compared to the recession between 2000 and 2015, as visible in Fig. 3. However, this is typical of glaciers in a state of disappearance (Kaser et al., 2010). A comparison of the loss rate with the glacier area extent changes indicates that the observed slowdown between 2016 and 2024 happened after the complete loss of glacier parts at lower altitudes, with the remaining glacier parts at higher altitudes only, where more favourable climate conditions for glaciers exist.

As important reason for the retreat of Puncak Jaya glaciers, the rise of mean annual air temperatures at the 550 hPa pressure level has been reported, with a rise of ∼ 1 °C alone at glacier altitude between 1972 and 2000, which coincided with a near-zero probability of average daily air temperatures falling below freezing point at ∼ 4400 m a.s.l. (∼ 300 m below the glaciated areas) after 1997 (Permana et al., 2019; Prentice and Hope, 2007). Between 1997 and 2016, a high likelihood of surface air temperatures below freezing point only existed at the highest glacier reaches for a few hours during the night and early morning (Permana et al., 2019). Additional factors, such as sea surface temperature changes, changes in the phase of precipitation due to air temperature rise, changes in radiation absorption as well as El Niño Southern Oscillation and monsoon variability, are playing further roles (Permana, 2015; Prentice and Hope, 2007; Permana et al., 2019; Kincaid, 2007). Based on the locations of the glacier remnants, the topography appears to have some influence, as all present ice masses are located on the western and southwestern ridges of their respective mountains, facing away from the morning sun (when skies are most likely cloud-free). This effect was already demonstrated by Hastenrath and Kruss (1988) to play a role for vanishing tropical glaciers. However, due to the lack of long-term in-situ climatological datasets for the area, the direct local and regional climatic drivers are harder to identify (van Ufford and Sedgwick, 1998; Prentice and Hope, 2007).

In this brief communication, the strong recession of Puncak Jaya glaciers is documented, both for recent years and for the historic time range since the mid 19th century. New glacier surface areas for 2023 and 2024 on Puncak Jaya were determined, which closes an existing data gap. Besides, we transferred historic glacier extent data into a digital format combined with a thorough analogue and digital data acquisition and collection, resulting in an up-to-date overview map of Puncak Jaya glacier history, which ranges from ∼ 1850 to 2024. A detailed attribution of this glacier recession to climatological causes beyond the more general factors (outlined in Sect. 4) will, however, require additional studies (and in-situ data acquisition) due to the well-known scale problem for mountain regions (Mölg and Kaser, 2011). In light of the more frequent occurrence of small (tropical) glaciers in the future due to climate change, high- and highest-resolution optical imagery will become more important for surveying small glaciers in comparison to medium-resolution imagery (e.g. Hinzmann et al., 2024). It is expected that Puncak Jaya glaciers will disappear around 2030, if the observed annual area retreat rate since 2018 persists.

The new glacier extents for 2023 and 2024 as well as the reanalysed earlier extents of 2012, 2016, 2018 and of the historic maps of 1850, 1972 and 1987 are openly available in PANGAEA at https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.979847 (Ibel et al., 2025).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-19-6629-2025-supplement.

DI conducted the data analysis under supervision of CS and TM. The writing was led by DI, with contributions from TM and CS. All authors discussed the results and edited the manuscript.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a member of the editorial board of The Cryosphere. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We thank Joni L. Kincaid for providing data of glacier extent in 2002 and Donaldi S. Permana (BMKG Indonesia) for providing recent photos of East Northwall Firn and Carstensz glaciers. We also want to thank Planet Labs PBC for providing access to PlanetScope imagery via their PlanetLabs Education and Research Programme and CNES/Airbus DS/European Space Agency for providing access to Pléiades imagery (Proposal ID: PP0093912). The constructive comments of two reviewers and the editor helped to improve the manuscript further.

This paper was edited by Ian Delaney and reviewed by Mauri Pelto and one anonymous referee.

Airbus Defence and Space Intelligence: Pléiades Imagery: User Guide, https://storage.googleapis.com/p-ssp-iep-prod-8ff-strapi-uploads/210415_Airbus_Pleiades_Imagery_user_guide_be12b8f35b/210415_Airbus_Pleiades_Imagery_user_guide_be12b8f35b.pdf (last access: 26 January 2025), 2021.

Allison, I.: Morphology and dynamics of the tropical glaciers of Irian Jaya, Zeitschrift für Gletscherkunde und Glazialgeologie, 10, 129–152, 1974.

Allison, I. and Kruss, P.: Estimation of Recent Climate Change in Irian Jaya by Numerical Modeling of Its Tropical Glaciers, Arctic Alpine Res., 9, 49–60, https://doi.org/10.2307/1550408, 1977.

Allison, I. and Peterson, J. A.: Ice areas on Mt. Jaya: Their extent and recent history, in: The equatorial glaciers of New Guinea: Results of the 1971 - 1973 Australian Univ., expeditions to Irian Jaya, survey, glaciology, meteorology, biology and palaeoenvironments, edited by: Hope, G. S., Peterson, J. A., Radok, U., and Allison, I., Balkema, Rotterdam, 27–38, ISBN 9061910129, 1976.

Anderson, E. G.: Topographic survey and cartography, in: The equatorial glaciers of New Guinea: Results of the 1971 - 1973 Australian Univ., expeditions to Irian Jaya, survey, glaciology, meteorology, biology and palaeoenvironments, edited by: Hope, G. S., Peterson, J. A., Radok, U., and Allison, I., Balkema, Rotterdam, 15–26, ISBN 9061910129, 1976.

Ballard, C.: The Colijn Expedition to the Carstensz Peaks (1936), in: Race to the snow: Photography and the exploration of Dutch New Guinea, 1907-1936, edited by: Ballard, C., Vink, S., and Ploeg, A., Amsterdam, 35–42, ISBN 9068325116, 2001.

Bowler, J. M., Hope, G. S., Jennings, J. N., Singh, G., and Walker, D.: Late Quaternary Climates of Australia and New Guinea, Quaternary Res., 6, 359–394, https://doi.org/10.1016/0033-5894(67)90003-8, 1976.

Brown, I. M.: Quaternary glaciations of New Guinea, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 9, 273–280, https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-3791(90)90022-3, 1990.

Carrivick, J. L., Davies, M., Wilson, R., Davies, B. J., Gribbin, T., King, O., Rabatel, A., García, J.-L., and Ely, J. C.: Accelerating Glacier Area Loss Across the Andes Since the Little Ice Age, Geophys. Res. Lett., 51, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024GL109154, 2024.

Coljin, A. H.: Naar de eeuwige sneeuw van tropisch Nederland, Amsterdam, 1937.

Dozy, J.: Eine Gletscherwelt in Niederländisch-Neuguinea, Zeitschrift für Gletscherkunde, für Eiszeitforschung und Geschichte des Klimas, XXVI, 45–51, 1938.

Dozy, J., Erdman, D., Jong, W., Krol, G., and Schouten, C.: Geological results of the Carstensz Expedition 1936, Leidse Geologische Mededelingen, 11, 68–131, 1939.

Fountain, A. G., Glenn, B., and Mcneil, C.: Inventory of glaciers and perennial snowfields of the conterminous USA, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 15, 4077–4104, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-4077-2023, 2023.

Fox-Kemper, B., Hewitt, H., Xiao, C., Aðalgeirsdóttir, G., Drijfhout, S., Edwards, T., Golledge, N., Hemer, M., Kopp, R., Krinner, G., Mix, A., Notz, D., Nowicki, S., Nurhati, I., Ruiz, L., Sallée, J.-B., Slangen, A., and Yu, Y.: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change, in: Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis, edited by: Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J., Maycock, T., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., and Zhou, B., Cambridge University Press, 1211–1362, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.011, 2021.

Gorin, A. L., Shakun, J. D., Jones, A. G., Kennedy, T. M., Marcott, S. A., Goehring, B. M., Zoet, L. K., Jomelli, V., Bromley, G. R. M., Mateo, E. I., Mark, B. G., Rodbell, D. T., Gilbert, A., and Caffee, M. W.: Recent tropical Andean glacier retreat is unprecedented in the Holocene, Science, 385, 517–521, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adg7546, 2024.

Harrer, H.: Ich komme aus der Steinzeit: Ewiges Eis im Dschungel der Südsee, Berlin/Frankfurt am Main/Wien, 1963.

Hastenrath, S. and Kruss, P. D.: The role of radiation geometry in the climate response of mount kenya's glaciers, part 2: Sloping versus horizontal surfaces, J. Climatol., 8, 629–639, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.3370080606, 1988.

Hinzmann, A., Mölg, T., Braun, M., Cullen, N. J., Hardy, D. R., Kaser, G., and Prinz, R.: Tropical glacier loss in East Africa: recent areal extents on Kilimanjaro, Mount Kenya, and in the Rwenzori Range from high-resolution remote sensing data, Environ. Res.: Climate, 3, 11003, https://doi.org/10.1088/2752-5295/ad1fd7, 2024.

Hock, R., Rasul, G., Adler, C., Cáceres, B., Gruber, S., Hirabayashi, Y., Jackson, M., Kääb, A., Kang, S., Kutuzov, S., Milner, A., Molau, U., Morin, S., Orlove, B., and Steltzer, H.: High Mountain Areas, in: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, edited by: Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D., Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Nicolai, M., Okem, A., Petzold, J., Rama, B., and Weyer, N. M., Cambridge, New York, NY, 131–202, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157964.004, 2022.

Hope, G. S.: Mt. Jaya: The area and its exploration, in: The equatorial glaciers of New Guinea: Results of the 1971 - 1973 Australian Univ., expeditions to Irian Jaya, survey, glaciology, meteorology, biology and palaeoenvironments, edited by: Hope, G. S., Peterson, J. A., Radok, U., and Allison, I., Balkema, Rotterdam, 1–14, ISBN 9061910129, 1976.

Hope, G. S. and Peterson, J. A.: Palaoenvironments, in: The equatorial glaciers of New Guinea: Results of the 1971 - 1973 Australian Univ., expeditions to Irian Jaya, survey, glaciology, meteorology, biology and palaeoenvironments, edited by: Hope, G. S., Peterson, J. A., Radok, U., and Allison, I., Balkema, Rotterdam, 173–206, ISBN 9061910129, 1976.

Hope, G. S., Peterson, J. A., Radok, U., and Allison, I. (Eds.): The equatorial glaciers of New Guinea: Results of the 1971 - 1973 Australian Univ., expeditions to Irian Jaya, survey, glaciology, meteorology, biology and palaeoenvironments, Balkema, Rotterdam, ISBN 9061910129, 1976.

Ibel, D., Mölg, T., and Sommer, C.: Surveying tropical glacier change on Puncak Jaya (Irian Jaya/West Papua, Indonesia) in recent years using multispectral high-resolution satellite imagery, publishing updated map of change 1850-2024, PANGAEA [data set], https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.979847, 2025.

Kaser, G. and Osmaston, H.: Tropical glaciers, International hydrology series, Cambridge, https://doi.org/10.3189/172756503781830782, 2002.

Kaser, G., Mölg, T., Cullen, N. J., Hardy, D. R., and Winkler, M.: Is the decline of ice on Kilimanjaro unprecedented in the Holocene?, The Holocene, 20, 1079–1091, https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683610369498, 2010.

Kincaid, J. L.: An assessment of regional climate trends and changes to the Mt. Jaya glaciers of Irian Jaya, Master thesis, Texas A&M University, https://hdl.handle.net/1969.1/5804 (last access: 26 January 2025), 2007.

Klein, A. G. and Kincaid, J. L.: Retreat of glaciers on Puncak Jaya, Irian Jaya, determined from 2000 and 2002 IKONOS satellite images, J. Glaciol., 52, 65–79, https://doi.org/10.3189/172756506781828818, 2006.

Le Roux, C.: De Bergpapoea's van Nieuw-Guinea en hun woongebied: Eerste Deel, Koninklijk Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, OCLC number: 37836037, 1948.

Linsbauer, A., Huss, M., Hodel, E., Bauder, A., Fischer, M., Weidmann, Y., Bärtschi, H., and Schmassmann, E.: The New Swiss Glacier Inventory SGI2016: From a Topographical to a Glaciological Dataset, Front. Earth Sci., 9, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2021.704189, 2021.

Löffler, E.: Neuester Stand der Quartärforschung in Neuguinea, Eiszeitalter und Gegenwart, 30, 109–123, 1980.

Mölg, T. and Kaser, G.: A new approach to resolving climate-cryosphere relations: Downscaling climate dynamics to glacier-scale mass and energy balance without statistical scale linking, J. Geophys. Res., 116, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JD015669, 2011.

Mölg, T., Cullen, N. J., Hardy, D. R., Winkler, M., and Kaser, G.: Quantifying Climate Change in the Tropical Midtroposphere over East Africa from Glacier Shrinkage on Kilimanjaro, J. Climate, 22, 4162–4181, https://doi.org/10.1175/2009JCLI2954.1, 2009.

Mölg, T., Hardy, D. R., Collier, E., Kropač, E., Schmid, C., Cullen, N. J., Kaser, G., Prinz, R., and Winkler, M.: Mesoscale atmospheric circulation controls of local meteorological elevation gradients on Kersten Glacier near Kilimanjaro summit, Earth Syst. Dynam., 11, 653–672, https://doi.org/10.5194/esd-11-653-2020, 2020.

Paul, F., Barrand, N. E., Baumann, S., Berthier, E., Bolch, T., Casey, K., Frey, H., Joshi, S. P., Konovalov, V., Le Bris, R., Mölg, N., Nosenko, G., Nuth, C., Pope, A., Racoviteanu, A., Rastner, P., Raup, B., Scharrer, K., Steffen, S., and Winsvold, S.: On the accuracy of glacier outlines derived from remote-sensing data, Ann. Glaciol., 54, 171–182, https://doi.org/10.3189/2013AoG63A296, 2013.

Paul, F., Rastner, P., Azzoni, R. S., Diolaiuti, G., Fugazza, D., Le Bris, R., Nemec, J., Rabatel, A., Ramusovic, M., Schwaizer, G., and Smiraglia, C.: Glacier shrinkage in the Alps continues unabated as revealed by a new glacier inventory from Sentinel-2, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 12, 1805–1821, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-12-1805-2020, 2020.

Permana, D. S., Thompson, L. G., Mosley-Thompson, E., Davis, M. E., Lin, P.-N., Nicolas, J. P., Bolzan, J. F., Bird, B. W., Mikhalenko, V. N., Gabrielli, P., Zagorodnov, V., Mountain, K. R., Schotterer, U., Hanggoro, W., Habibie, M. N., Kaize, Y., Gunawan, D., Setyadi, G., Susanto, R. D., Fernández, A., and Mark, B. G.: Disappearance of the last tropical glaciers in the Western Pacific Warm Pool (Papua, Indonesia) appears imminent, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 116, 26382–26388, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1822037116, 2019.

Permana, D. S.: Reconstruction of Tropical Pacific Climate Variability from Papua Ice Cores, Indonesia, PhD thesis, Ohio State University, 2015.

Permana, D. S.: Climate, precipitation isotopic composition and tropical ice core analysis of Papua, Indonesia, Master thesis, Ohio State University, 2011.

Peterson, J. A. and Peterson, L. F.: Ice retreat from the Neoglacial maxima in the Puncak Jayakesuma area, Republic of Indonesia, Zeitschrift für Gletscherkunde und Glazialgeologie, 30, 1–9, 1994.

Peterson, J. A., Hope, G. S., and Mitton, R.: Recession of snow and ice fields of Irian Jaya, Republic of Indonesia, Zeitschrift für Gletscherkunde und Glazialgeologie, 9, 73–87, 1973.

Planet Labs PBC: Planet Application Program Interface: In Space for Life on Earth, https://api.planet.com (last access: 26 January 2025), 2018.

Planet Labs PBC: Planet Imagery Product Specifications, 2023.

Prentice, M. L. and Glidden, S.: Glacier crippling and the rise of the snowline in western New Guinea (Papua Province, Indonesia) from 1972 to 2000, in: Altered Ecologies: Fire, climate and human influence on terrestrial landscapes: Terra Australis 32, edited by: Haberle, S., Prebble, M., and Stevenson, J., ANU Press, Canberra, 457–471, ISBN 9781921666803, 2010.

Prentice, M. L. and Hope, G. S.: Climate of Papua, in: The Ecology of Papua: Part One, edited by: Marshall, A. J. and Beehler, B. M., Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd., New York, 177–196, ISBN 978-1-4629-0679-6, 2007.

Prentice, M. L., Hope, G. S., Peterson, J. A., and Barrows, T. T.: The Glaciation of the South-East Asian Equatorial Region, in: Quaternary Glaciations - Extent and Chronology: A Closer Look, Vol. 15, edited by: Ehlers, J., Gibbard, P. L., and Hughes, P. D., Elsevier B.V., 1023–1036, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53447-7.00073-8, 2011.

Supari, Tangang, F., Juneng, L., and Aldrian, E.: Observed changes in extreme temperature and precipitation over Indonesia, Int. J. Climatol., 37, 1979–1997, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.4829, 2017.

Temple, P.: Nawok!: The New Zealand Expedition to New Guinea's highest mountains, London, J.M. Dent, London, OCLC number: 834920071, 1962.

Turpo Cayo, E. Y., Borja, M. O., Espinoza-Villar, R., Moreno, N., Camargo, R., Almeida, C., Hopfgartner, K., Yarleque, C., and Souza, C. M.: Mapping Three Decades of Changes in the Tropical Andean Glaciers Using Landsat Data Processed in the Earth Engine, Remote Sensing, 14, 1–21, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14091974, 2022.

van Ufford, A. Q. and Sedgwick, P.: Recession of the equatorial Puncak Jaya glaciers (∼ 1825 to 1995), Irian Jaya (Western New Guinea), Indonesia, Zeitschrift für Gletscherkunde und Glazialgeologie, 34, 131–140, 1998.

Wollaston, A. F. R.: An Expedition to Dutch New Guinea, The Geographical Journal, 43, 248–268, 1914.

World Glacier Monitoring Service WGMS: Latest glacier mass balance data, https://wgms.ch/latest-glacier-mass-balance-data/ (last access: 10 October 2025), 2024.

World Meteorological Organization: State of the Climate in the South-West-Pacific, WMO-No. 1324, ISBN 978-92-63-11324-5, 2022.