the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Pressurised water flow in fractured permafrost rocks revealed by borehole temperature, electrical resistivity tomography, and piezometric pressure

Samuel Weber

Michael Krautblatter

Ingo Hartmeyer

Markus Keuschnig

Rock slope instabilities and failures from permafrost rocks are among the most significant alpine hazards in a changing climate and represent considerable threats to high-alpine infrastructure. While permafrost degradation is commonly attributed to rising air temperature and slow thermal heat propagation in rocks, the profound impact of water flow in bedrock permafrost on warming processes is increasingly recognised. However, quantifying the role of water flow remains challenging, primarily due to the complexities associated with direct observation and the transient nature of water dynamics in rock slope systems. To overcome the lack of a quantitative assessment, we combine datasets of rock temperature measured in two deep boreholes (2016–2023), with electrical resistivity tomography measurements repeated monthly in 2013 and 2023; the site-specific temperature–resistivity relation determined in the laboratory with samples from the study area; and borehole piezometer data. Field measurements were carried out at the permafrost-affected north flank of the Kitzsteinhorn (Hohe Tauern range, Austria), which is characterised by significant water outflow from open fractures during the melt season. Borehole temperature data demonstrate a seasonal maximum of the permafrost active layer of 4–5 m. They further show abrupt temperature changes (∼ 0.2–0.7 °C) at 2, 3, and 5 m depth during periods with enhanced water flow and temperature regime changes between 2016–2019 and 2020–2022 at 10 and 15 m depth, which cannot be explained solely by conductive heat transfer. Electrical resistivity measurements repeated monthly reveal a massive decrease in resistivity from June to July and the initiation of a low-resistivity (< 4 kΩ m) zone in the lower part of the rock slope in June, gradually expanding to higher rock slope sections until September. We hypothesise that the reduction in electrical resistivity of more than an order of magnitude, which coincides with abrupt changes in borehole temperature and periods of high water heads up to 11.8 m, provides certain evidence of snowmelt water infiltration into the rockwall becoming pressurised within a widespread fracture network during the thawing season. This study shows that, in addition to slow thermal heat conduction, permafrost rocks are subjected to sudden push-like warming events and long-lasting rock temperature regime changes, favouring accelerated bottom-up permafrost degradation and contributing to the build-up of hydrostatic pressure, potentially leading to slope instability.

- Article

(10616 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Over the past decade, awareness of climate-change-related hazards in alpine environments has increased, including rock slope failures from warming permafrost rocks. Degrading permafrost in rockwalls can reduce the stability of rock slopes (Gruber and Haeberli, 2007), increasing the likelihood of slope failure and endangering mountain infrastructure (Duvillard et al., 2021b). Rising temperatures alter the mechanical properties of rock and ice (Krautblatter et al., 2013; Mamot et al., 2018), which can increase the number of rockfalls and rock slope failures in permafrost-affected rockwalls (Ravanel et al., 2017; Hartmeyer et al., 2020; Savi et al., 2021; Cathala et al., 2024b). Therefore, precise knowledge of changes in frozen rocks' thermal and mechanical regime is of particular interest to address mountain tourism's increased vulnerability and prevent or limit damage to high-alpine infrastructure (Duvillard et al., 2019).

Potential triggers of rock slope failure have been attributed to high water pressures (e.g. Fischer et al., 2010; Ravanel et al., 2017) that can arise from the infiltration of rainwater or meltwater from snow, glaciers, ice-filled joints, or permafrost. In some cases, the hydrological processes contributing to the destabilisation of the rock slope were directly evidenced by ice and water coating the scarp shortly after the event (e.g. Walter et al., 2020; Mergili et al., 2020; Cathala et al., 2024a). The infiltration capacity and hydraulic permeability of a rockwall are determined by the degree of fracturing, pore space characteristics, saturation, and temperature (Gruber and Haeberli, 2007). The surface water availability from snowmelt and rainfall for infiltration into steep rock slopes was recently estimated by a numerical energy balance model (Ben-Asher et al., 2023). Ice-filled fissures reduce the permeability compared to unfrozen fissures (Pogrebiskiy and Chernyshev, 1977), leading to perched water and the build-up of high hydrostatic pressures (Magnin and Josnin, 2021). Although the destabilising shear stress of high water levels on the rock mass is well known (Krautblatter et al., 2013), piezometric pressures have only been observed in permafrost regions on one rock glacier (Phillips et al., 2023; Bast et al., 2024) and in one open crack at shallow depth (Draebing et al., 2017). Direct observations of piezometric pressures in deep depths (> 10 m) have not yet been measured in permafrost-affected rockwalls but remain crucial for understanding hydrological processes and thus for the prospective prediction of rock slope failures.

Non-conductive heat transport due to water flow along fractures can rapidly raise the temperature, leading to the formation of thaw corridors, which potentially enhance local permafrost degradation (Gruber and Haeberli, 2007) and erosion of ice-filled clefts (Hasler et al., 2011a) compared to slow thermal heat propagation in rocks. The physical processes of water flux in frozen bedrock are intrinsically difficult to quantify; exhibit non-linear, complex behaviour; and are therefore poorly studied. Phillips et al. (2016) observed brief and intermittent thermal anomalies in borehole measurements in an alpine rock ridge, interpreted as water percolating through fractures after heavy precipitation. Seismic analysis and geophysical soundings have revealed seasonal variations in cleft-ice infill and meltwater percolation in fractures (Krautblatter et al., 2010; Keuschnig et al., 2017; Weber et al., 2018).

Changes in water and ice content can be detected by electrical resistivity tomography (ERT), which is a well-established method (e.g. Hauck, 2002; Schneider et al., 2013; Hilbich et al., 2022; Cimpoiasu et al., 2024) that has been increasingly applied in mountain permafrost environments in recent years (Herring et al., 2023). Monitoring active-layer dynamics and spatial and temporal permafrost evolution requires repeated ERT surveys, preferably using the same survey geometry and fixed installed electrodes. ERT monitoring over several years has demonstrated degrading permafrost associated with global warming (e.g. Mollaret et al., 2019; Scandroglio et al., 2021; Buckel et al., 2023). However, most monitoring approaches emphasise the inter-annual evolution of bedrock permafrost and often overlook seasonal variations in resistivity, especially during thawing periods.

ERT measurements offer valuable, indirect information, requiring either laboratory calibration (Krautblatter et al., 2010) or ground temperature for quantitative interpretation. Borehole temperature measurements are direct thermal observations. They provide point-scale data along the borehole profile in a heterogeneous alpine terrain but do not allow for a differentiation between water and ice close to 0 °C. The freezing point of water can be shifted depending on rock properties, salinity, and pore pressure (Arenson et al., 2022), allowing for unfrozen water content at subzero temperatures. In addition, temperature changes may be slowed by latent heat effects while significant changes in the water-to-ice ratio occur. To reduce uncertainties in the characterisation of subsurface properties, a complementary approach that combines borehole observation and geophysical data such as electrical resistivity (e.g. Hauck, 2002; Etzelmüller et al., 2020) and/or seismic refraction data (e.g. Hilbich, 2010; Wagner et al., 2019) is required.

The influence of water fluxes on the thermal and hydrostatic regime in bedrock permafrost remains a key challenge, despite the demonstrated link between hydrological fluxes and rock slope instability. In this study, we address the lack of quantitative and in situ observations of rockwall hydrology by analysing repeated ERT measurements, ground temperature data from two deep boreholes (2016–2023), and piezometric pressure data (2024) at the fractured north face of the Kitzsteinhorn (Hohe Tauern range, Austria). This study highlights the importance of a higher geoelectrical measurement frequency compared to annual campaigns and an integrated approach of different indirect and direct measurements, emphasising the significance of melt period analysis in delineating both temporal patterns and the spatial distribution of intense water flow within fractures. These insights will improve our knowledge of the complex seasonal water flow in rockwalls that potentially accelerate permafrost degradation and contribute to promoting and triggering factors for rock slope failures.

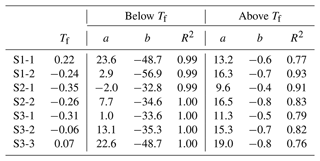

Figure 1(a) Detailed view of the investigated, north-facing rockwall below the Kitzsteinhorn summit station (Hohe Tauern range, Austria) and the position of the ERT profile, the two deep boreholes (B1, B2), and the piezometer. (b) The geotechnical setting of the rock face is described by the schematic representation of the main discontinuities of K1, K2, K3, and K4 and the schistosity SF, as well as (c) the dip angle and direction of their mean set planes.

The investigated rockwall is located in the summit region of the Kitzsteinhorn (3203 m a.s.l.), part of the Hohe Tauern range in Austria (Fig. 1). The Kitzsteinhorn region is characterised by rocks of the Penninic Bündner Schist Formation in the Tauern Window and belongs to the Glockner Nappe. The lithology in the study area is dominated by calcareous mica schists traversed by a scaly band of serpentinite parallel to the schistosity that dips steeply at approximately 45° to the NNE (Cornelius and Clar, 1935; Hoeck et al., 1994; Hartmeyer et al., 2020).

The north face of the Kitzsteinhorn exhibits a significant degree of fracturing, characterised by joint openings of up to 20 cm, predominantly along cleavage planes (Schober et al., 2012). The development of the enormous number of joint sets was favoured by stress release and intense physical weathering processes (Hartmeyer et al., 2012). The main joint sets are K1, which has a sub-vertical dip to the west, and K2, which features a steep dip to the southwest (Fig. 1). K3 and K4 are less abundant. K3 dips from a medium steepness to flat to the S-SSE, and K4 dips steeply to the NW. Laboratory tests of mica-schist rocks with ice-filled joints have shown that the shear resistance along rock–ice interfaces follows a temperature- and stress-dependent failure criterion, where warming and unloading lead to a mechanical destabilisation and can lead to self-enforced rock slope failure (Mamot et al., 2020). Keuschnig et al. (2017) installed the ERT profile at the north-facing rockwall below the station of the Kitzsteinhorn cable car in 2012, ranging from an elevation of 2965 to 3017 m a.s.l. (Fig. 1). The flank has been severely affected at its base by the rapid retreat of the Schmiedingerkees glacier, which caused increased rockfall activity in the lower part of the rockwall, with single detachments of up to 880 m3 (Hartmeyer et al., 2020). Several rockfall events have damaged the lower part of the ERT profile. As a result, the electrical resistivity measurements, carried out monthly from June to September 2023, now cover an elevation range from 2976 to 3017 m a.s.l. The slope gradient of the rock face increases as it approaches the glacial cirque and is averaged at 47° (Keuschnig et al., 2017). Weather conditions at the study site in 2013 and 2023 were analysed using recordings from the Gletscherplateau and Alpincenter weather stations, including air temperature, snow height, and rainfall (Fig. A1).

This study is part of the “Open-Air-Lab Kitzsteinhorn” (Keuschnig et al., 2011; Hartmeyer et al., 2012), a comprehensive long-term project to monitor the response of bedrock permafrost to climatic change across multiple scales. Empirical–statistical calculations by Schrott et al. (2012) on the distribution of permafrost in the Hohe Tauern region indicate a high permafrost probability above 2500 m a.s.l. on north-facing rockwalls and above 3000 m a.s.l. on south-facing slopes of the Kitzsteinhorn. In addition, permafrost has been detected by electrical resistivity measurements in the northern section of the Hannah-Stollen tunnel, which connects the Kitzsteinhorn cable car station to the south side at an elevation of approximately 3000 m a.s.l. (Hartmeyer et al., 2012).

3.1 Borehole temperature measurements

Rock temperature measurements in two deep boreholes close to the geoelectrical profile have been conducted since December 2015 and were analysed until December 2023. Borehole B1 is situated close to electrode 1 (x = 0 m) at an elevation of 3030 m a.s.l., and borehole B2 is positioned between electrodes 22 (x = 42 m) and 23 (x = 44 m) at an elevation of 2970 m a.s.l. Both boreholes were drilled perpendicular to the surface and the schistosity, reaching a depth of 22 m (B1) and 30 m (B2). The temperature inside both boreholes was recorded based on a highly sensitive measuring system: after drilling, B1 and B2 were equipped with water- and airtight polyethylene casings interrupted by non-corrosive brass rings at the designated depths of the temperature sensors. The annulus was filled with concrete to avoid water/air circulation and ice formation in the void between the casing and ambient bedrock. A chain of customised high-precision Pt100 thermistors (accuracy ±0.03 °C) was inserted into the casing and established direct mechanical contact with the brass rings of the casings. Due to the high thermal conductivity of the brass rings and their direct physical connection to the sensors, this setup enables improved thermal coupling between the temperature sensor and surrounding rock mass compared to most other systems. The system used for the present study thus responds sensitively to (minor) changes in temperature and is well-suited to record short-term fluctuations of bedrock temperature. Sensors were installed at 0.1, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 15, 20, 21.5 (only B1), 25 (only B2), and 30 m (only B2) depth. The measuring interval was set to 10 min. Scaled images of the borehole walls were acquired using an optical scanner to identify and locate discontinuities. These images provided insight into parameters including joint frequency and aperture over the entire depth of B1 (22 m) and to a depth of approximately 15 m in B2.

Lightning strikes damaged several thermistors throughout the long-term monitoring (2016–2023), leading to data gaps starting in June 2017 (B2 at 0.5, 10 m), July 2019 (B2 at 20 m), June 2020 (B2 at 7 m), September 2020 (B2 at 25 m), April 2023 (B1 at 20 m), and June 2023 (B1 at 7, 10, 21.5 m; B2 at 1 m). Warming releases resulting from construction activities for summit station maintenance in summer 2023, mainly due to drilling operations near B1, could have affected ground temperature measurements. Consequently, we excluded the affected datasets from B1 (August–December 2023).

The thermistor signals in B1 and B2 were analysed for irregularities and characteristics typical of non-conductive heat transfer. Near-surface temperatures (depth < 2 m) were excluded from the analysis as they are characterised by short-term fluctuations with large amplitudes, making distinguishing between changes induced by non-conductive heat transfer and meteorologically forced changes complex. For the recordings in 2 and 3 m depth, thermal anomalies were identified using the first derivative with a moving average of 12 points (i.e. measurement interval of 2 h). High signals in the first derivative were manually reviewed for characteristics typical of non-conductive heat transfer, which exhibit a temperature rise of up to 0.7 °C in less than 2 h. Sudden, significant changes between two measurements (10 min) with a return to the previous temperature level are caused by overvoltage effects following lightning strikes and were therefore not considered further. Due to the smooth curvature of the thermal signals in 5 m depth, thermal anomalies were directly visible in the data and were manually determined.

3.2 ERT data acquisition

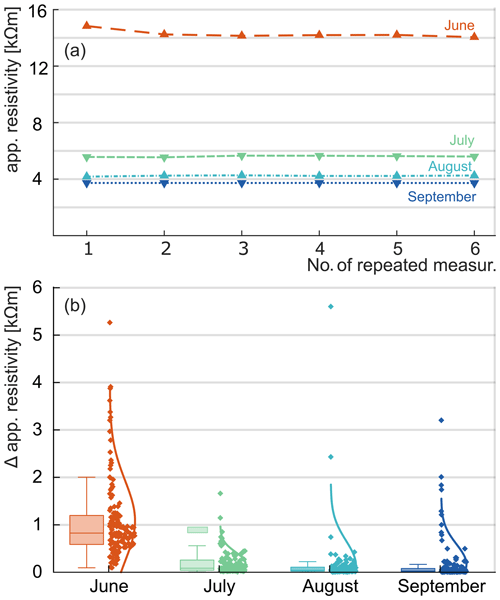

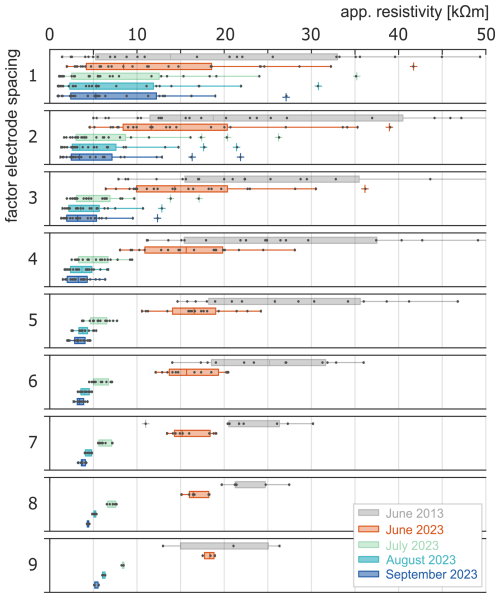

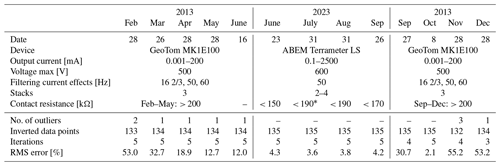

A general description of the ERT procedure can be found in Appendix B. The ERT profile used for the present study was installed in 2012 and initially used for a year-long continuous subsurface monitoring of permafrost conditions using automated ERT starting in February 2013 (Keuschnig et al., 2017). Therefore, 37 electrodes were permanently drilled into the bedrock at intervals of 2 m. Stainless-steel climbing bolts with a length of 90 mm and a diameter of 10 mm were preferred to fixed stainless-steel screws (Krautblatter and Hauck, 2007) as they allowed for good electrical contact with the bedrock without applying metallic grease and ensured long-term durability. The automated ERT measurements were performed from February–December 2013 on a 4 h sampling interval using Wenner configuration, as it provides the best signal-to-noise ratio in permafrost rockwalls (Zhou and Dahlin, 2003) and good horizontal resolution (Hauck and Kneisel, 2008). Two lightning strikes severely damaged the hardware and prevented most measurements between June and September 2013. We performed ERT measurements over a 24 h period at the end of each month from June to September 2023 using the same protocol type to fill this data gap. We analysed short-term variations in electrical resistivity values for each measurement campaign to exclude random errors and quantify the respective measurement uncertainty (Fig. B1). Due to several rockfall events, the lower part of the ERT profile was damaged, and only the top 30 fixed electrodes could be used in 2023 (i.e. 58 m profile length). To enable comparison of the 2013 and 2023 data series on a temporal and spatial scale, we selected tomograms at the end of each month of the automated ERT measurements in 2013 (February–June and September–December) and shortened them to the same profile length (electrodes 1–30). Further technical details of the respective ERT measurements are given in Table B1.

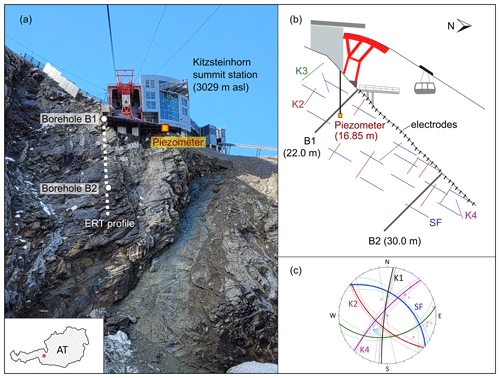

Figure 2Weather and rock surface conditions on the days of ERT measurements in 2023 described by mean daily air temperature (MDAT) derived from the nearby (∼ 500 m distance) Gletscherplateau (GP) weather station and estimated values of snow cover area (SCA) and snow height (SH). During the ERT measurements in June and July, pronounced surface runoff was observed in the lower part of the ERT profile.

The ERT measurements conducted in 2023 were carried out under varying weather conditions (Fig. 2). A thin layer of ice partially covered the rock surface during the morning and night of the ERT measurements in June, while significant surface runoff was observed passing the lower part of the ERT profile during the afternoon of the June campaign and throughout the measurement period in July. During ERT observations in August and September, most of the rockwall was covered by snow, reaching a height of up to 10 cm. Mean daily air temperature derived from a nearby weather station on Gletscherplateau (distance of ∼ 500 m, 2940 m a.s.l.) indicated positive mean values for all days of ERT measurements in 2023. Data points with considerable deviations from neighbouring values were manually filtered, resulting in a maximum of 2 % of data points per measurement being excluded from further data processing. All ERT measurements were inverted using the software package Res2DInv (Loke and Barker, 1996) with adapted settings for permafrost rock faces. Robust inversion routines with half-electrode spacing and mesh refinement were applied to cope with the expected high electrical resistivity gradients (Krautblatter and Hauck, 2007). After four to five iterations, a reasonable level of convergence was achieved without overfitting the data. Resistivity models with a high root mean square (RMS) error between the modelled and observed data are obtained, particularly during the winter months when frozen surface conditions impede the coupling of electrodes. Contact resistance values vary seasonally (Herring et al., 2023); in our case, values < 190 kΩ were observed during summer measurements, while values > 200 kΩ were mainly measured during winter measurements (Table B1). The high contact resistances (> 200 kΩ) could not be mitigated due to safety issues of accessing the problematic electrodes during the snow-covered rock face period. However, an assumption of inaccuracy and subsequent complete exclusion of the affected datasets, justified by high contact resistances and high RMS errors, would make it impossible to provide all-season ERT observations. We, therefore, retained the datasets of the winter measurements (February–May and September–December 2013) but withheld detailed interpretation in recognition of the potential presence of noise. In addition, the change in the raw data, i.e. the apparent resistivity, of the different measurements (June 2013, June–September 2023) was analysed in relation to the investigation depths to exclude artefacts from the inversion (Fig. B2). A summary of the data post-processing is given in the Appendix (Table B1), as well as the differences in the resistivity between the tomograms from June–September 2023 (Fig. B3).

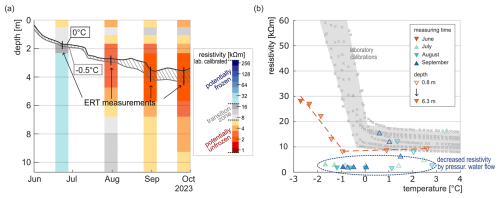

3.3 Laboratory calibration of the temperature–resistivity relation

The temperature–resistivity relation was derived from laboratory experiments of seven cylindrical samples (∅ = 80 mm) drilled from four calcareous mica-schist rock samples from the study side. The core samples were saturated for several weeks with tap water. At the chemical equilibrium (∼ 17 °C), water conductivity was 0.058 ± 0.002 S m−1, which is in the same order of magnitude as snowmelt water from the study site, with a conductivity of 0.014 S m−1. The full saturation of pore spaces was achieved under atmospheric pressure, as applying a vacuum would result in higher water absorption, which is less representative of field conditions (Krus, 1995; Sass, 1998). However, the free saturation method is likely subject to the occurrence of air bubbles (Draebing and Krautblatter, 2012), which may complicate the interpretation of the results.

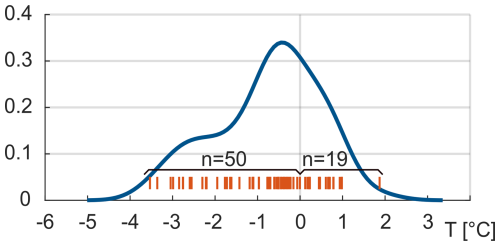

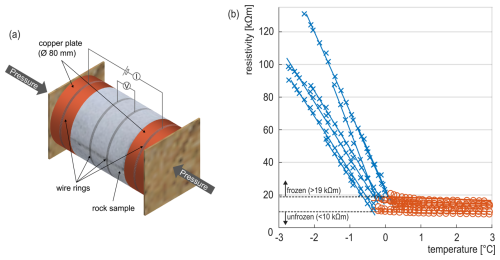

Figure 3(a) Simplified schematic illustrating the setup of the laboratory calibration. (b) Temperature–resistivity relation of laboratory experiments of seven mica-schist core samples indicating unfrozen conditions under 10 kΩ m and frozen conditions above 19 kΩ m.

Figure 3a illustrates the experimental setup for the laboratory electrical resistivity measurements. Two copper plates were placed on the grounded end faces of the samples as current electrodes (A and B). For the voltage electrodes (M and N), copper pipe clamps were installed around the core sample with equal spacing between the electrodes. Pressure was applied to the current electrodes to ensure good electrical contact. Resistivity ρ was calculated from the cross-section of the core sample A, the applied voltage V, the distance between the voltage electrodes L, and the resulting current I (Telford et al., 2004).

Temperature of the core samples was controlled by a freezing chamber which can be regulated in 0.1 °C increments. The rock samples were slowly warmed from −3 to 3 °C with a gradient of 0.3 °C h−1 to ensure temperature homogeneity. To avoid electrical interference, rock temperature was measured on a second, characteristically identical sample at depths of 25 and 40 mm with two thermometers (Greisinger GMH 3750, with 0.1 °C accuracy GTF 401 sensors). The samples were loosely covered with plastic film and ventilated to prevent drying and thermal layering. According to the field investigations, continuous resistance measurements were done with ABEM Terrameter LS using a minimum current of 0.1 mA and a maximum voltage output of 600 V.

The electric properties of water-saturated rocks are determined by the ionic transport in the liquid phase and, therefore, by the number of interconnected pores. The well-known empirical law developed by Archie (1942) relates the resistivity ρ to the functional porosity ϕ, the resistivity of the pore water ρw, and the fraction of the pore space occupied by liquid water S:

where a, n, and m are empirically determined constants. At subzero temperatures and under partially frozen conditions, the electrical properties of the rock depends on the remaining unfrozen water content in the pores. As the temperature drops to the equilibrium freezing temperature, pore water saturation decreases while the resistivity of the pore water also decreases due to the migration of electrolytes from the freezing water to the remaining unfrozen water content, resulting in increased electrolyte concentration. Above the equilibrium freezing temperature, the resistivity of the rock is indirectly related to temperature changes, as temperature affects the mobility of the solute electrolytes.

3.4 Piezometer installation

The piezometer sensor GEOKON 4500S (accuracy ±0.1 % from 0–7 bar) was installed in a vertical borehole (∅ = 90 mm, 20.5 m depth) close to the summit station (Fig. 1). The desired piezometer tip location was determined by the scaly band of serpentinite, identified through optical scanning of the borehole walls between 16.85 and 17.70 m depth. Consequently, the bottom of the borehole was filled with impermeable cement, followed by the isolated collection zone consisting of the piezometer sensor positioned within a bag of filter sand (∅ = 90 mm, ∼ 30 cm length) precisely at the upper boundary surface of the calcareous mica schists and serpentinite at a depth of 16.85 m. The cavity between the porous filter stone and the diaphragm was filled with a water–glycol mixture to prevent freezing damage to the piezometer diaphragm. The borehole above the water permeable collection zone was subsequently sealed with impermeable bentonite and cement.

A thermistor integrated into the housing of the piezometer sensor measured the temperature (accuracy of ±0.5 °C between −80 and +150 °C). The vibrating wire and thermistor are connected to a wireless Worldsensing LS-G6-VW data logger, which includes a barometer (relative accuracy of ±12 hPa), and transmits the hourly measured data via LoRa (long-range) communication. The pressure data were calculated with temperature and barometric corrections using the following equation (GEOKON, 2024):

where R is the measured pressure reading, R0 is the initial zero pressure reading, G is the linear calibration factor, T is the measured temperature, T0 is the initial zero temperature, K is the thermal factor, S is the measured barometric pressure, and S0 is the initial zero barometric pressure. Based on the specific calibration of the installed vibrating wire pressure transducer by GEOKON, G was determined to −0.1659 kPa per digit and K was determined to 0.0115 kPa °C−1. The recording began at the end of October 2023; however, to exclude long-lasting warming effects from the drilling activities, we analysed the dataset starting in January 2024 and continuing to mid-June 2024.

4.1 Borehole temperature and thermal anomalies

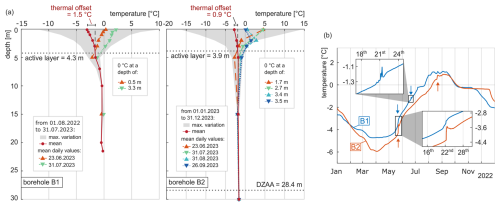

Interpolated borehole temperature recorded on the days of ERT measurements in 2023 indicate subzero subsurface conditions below depths of 0.5 m (B1) and 1.7 m (B2) in June, 3.3 m (B1) and 2.7 m (B2) in July, 3.4 m in August (B2), and 3.5 m in September (B2) (see Fig. 4a). The annual variations in ground temperature and the characteristic parameters of active-layer thickness (ALT), depth of zero annual amplitude (DZAA), and thermal offset were calculated for B2 for 2023, while for B1, the year before construction activities for summit station maintenance close to the borehole (August 2022–July 2023) was analysed. The seasonal maximum of the ALT was reached at a depth of 4.3 m in B1 and of 3.9 m in B2; the DZAA, defined by the annual temperature amplitude of less than 0.1 °C, was only reached in B2 at around 28.4 m (Fig. 4a). The thermal offset, defined by the difference between the annual mean ground surface temperature (i.e. temperature recording at 0.1 m depth) and the temperature at the permafrost table (Burn and Smith, 1988), is generally considered impracticable for fractured bedrock due to the highly variable microclimate and active-layer thickness (Hasler et al., 2011b). However, in our specific case, both boreholes suggest that the permafrost table depths are within a similar range. Therefore, considering the potential variability in microclimate, we propose that the concept of thermal offset is practicable and demonstrate positive values (B1 at 1.5 °C, B2 at 0.9 °C).

Figure 4(a) Ground temperature in boreholes B1 and B2 on the ERT measurement days from June to September 2023. The maximum annual variation of the ground temperature, the thickness of the active layer, the depth of zero annual amplitude (DZAA), and the mean annual ground temperature were determined for representative periods (B1: the year before construction activities for summit station maintenance close to the borehole started in August 2023; B2: the year 2023). (b) Thermal anomalies (abrupt temperature changes) found in the borehole temperature data, exemplified by the record taken at 3 m depth from 2022.

The quasi-sinusoidal temperature curves recorded over the observation period at 2, 3, 5, 10, and 15 m depth suggest that heat transport in the intact rock mass is dominated by conduction (Fig. 5). Nonetheless, borehole temperature showed 69 abrupt changes (thermal anomalies) at 2 and 3 m depth (B1, B2). Borehole temperatures at greater depths from 5–30 m are likely less sensitive to heat transfer from percolating water but exhibited 13 irregularities at 5 m depth (B1, B2) and notable changes in the quasi-sinusoidal pattern since 2020 at 10 and 15 m depth (B1). All abrupt changes and irregularities in the borehole temperature occurred between late May and September.

Figure 5Thermal anomalies in rock temperature throughout the observation period (2016–2023): identified at 2 and 3 m depth (B1, B2) by abrupt changes using the first deviation with a moving average of a sample window size of 2 h and by irregularities and changes in the quasi-sinusoidal pattern observed at greater depths (B1: 5, 10, 15 m; B2: 5 m). Dashed lines mark an event of thermal disturbance, which mainly occurred between May and September. Thermistors showing no thermal anomaly (n.t.a.) or damage (N/A) are indicated accordingly. The yellow bars highlight the periods of thermal anomalies across all observed depths in B1 and B2 for each year.

Optical borehole imaging shows a pronounced occurrence of clefts with apertures of up to 5 cm in the first 10 m in B1 and B2 and intact rock mass of calcareous mica schist with marked schistosity at greater depths (Fig. 5). Thermistors installed close or within clefts or areas of schistosity exhibit a higher frequency of thermal anomalies, as evidenced by the counts recorded (e.g. B1 at 2 m: 18, B2 at 3 m: 25), in contrast to thermistors installed at a greater distance, not exceeding 50 cm, from discontinuities (B2 at 2 m: 10, B1 at 3 m: 16). Most of the thermal anomalies result in the warming of the rock mass, while only two events in August and September 2017 induced cooling in B2 at depths of 3 m. The initial rock temperature shortly before rapid changes at 2 and 3 m depth (B1 and B2) indicates that the push-like warming and cooling events were recorded mostly during frozen conditions of the surrounding rock mass (72 % of thermal anomalies, Fig. C1).

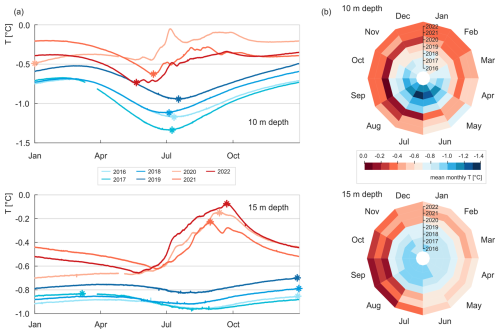

Figure 6Borehole temperature at depths of 10 and 15 m between 2016 and 2022 in B1. (a) Thermal signals at 10 m depth, with minimal values highlighted (top), and at 15 m depth, with maximal values highlighted (bottom). (b) Mean monthly temperature values, with each ring representing a measurement year and the radius increasing for more recent observation years.

Pluriannual changes in the temperature regime were observed between 2016–2019 and 2020–2022 at depths of 10 and 15 m in borehole B1. These changes were characterised by a quasi-sinusoidal pattern of rock temperature from 2016–2019, followed by rapid and irregular warming between 2020–2022 (Fig. 6a). Minimal annual rock temperatures at 10 m depth ranged from −1.34 to −0.94 °C from 2016–2019, increasing to −0.73 to −0.49 °C from 2020–2022. Maximal annual rock temperatures were observed in winter and spring from 2016–2019, ranging from −0.85 to −0.70 °C, and shifted to summer months from 2020–2022, with temperatures between −0.23 and −0.06 °C. The most pronounced changes in mean monthly rock temperatures were recorded in July at 10 m depth (2017: −1.31 °C, 2020: −0.16 °C) and in September at 15 m depth (2017: −0.95 °C, 2022: −0.10 °C) (see Fig. 6b).

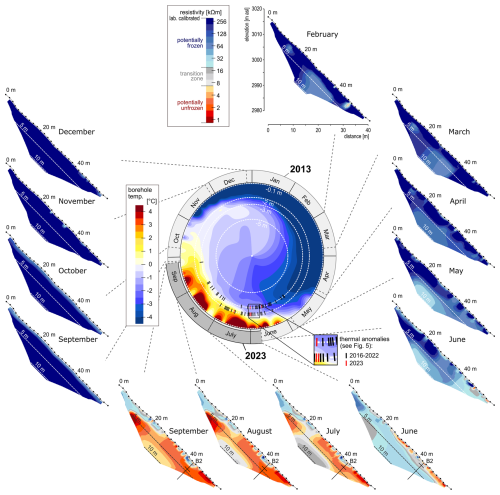

The polar plot in the centre of Fig. 7 shows a 1-year bedrock temperature cycle measured in B2 from January to December 2023. Rock temperature at depth shows a delayed and damped response to cooling and warming. At B2, for instance, a temperature maximum at 5 m was recorded in late December (−0.6 °C), while the minimum was registered in early May (−3.4 °C). The zero-curtain effect, i.e. an isothermal state where rock temperature stagnates close to 0 °C due to the release of latent heat (Outcalt et al., 1990), was most pronounced at 3 m depth in B2 (Fig. 5).

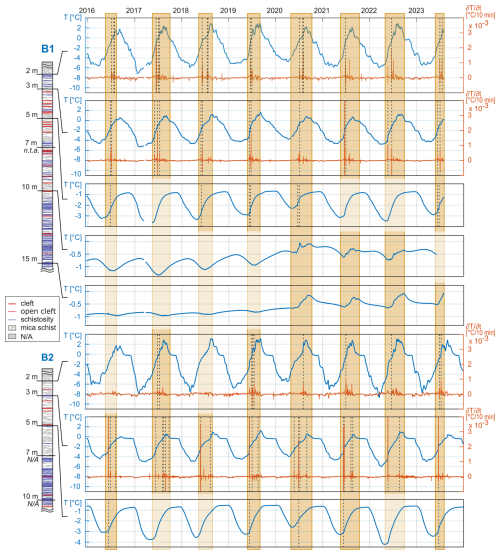

4.2 Seasonal variations in ERT

The seasonal evolution of the ERT data acquired from February–June 2013, June–September 2023, and September–December 2013 are shown in Fig. 7. In February, resistivity values greater than 64 kΩ m were observed throughout the profile except for a small area of measurement noise (x = 46–48 m). Only slight decreases in resistivity occurred in March 2013 and April 2013 at depths between 5 and 10 m and over the entire observation depth (0–10 m) in April 2013, June 2013, and June 2023. Nevertheless, electrical resistivity values remained above 32 kΩ m, indicating frozen rock and air-/ice-filled joints. Borehole temperature data from B2 (Fig. 4a) suggest an active-layer thickness of approximately 1.7 m at the time of the ERT measurement in June 2023, which is in good agreement with near-surface (∼ 0–2 m depth) electrical resistivity values of less than 12 kΩ m in the lower part of the tomogram (∼ x = 28–58 m). The most pronounced seasonal variation in electrical resistivity occurs in summer (Fig. B1), coinciding with all abrupt changes and irregularities in borehole temperature (Fig. 7). In July, the low-resistivity zone in the lower part of the tomogram expands to ∼ 5 m depth, while resistivity drops to around 4 kΩ m. In July and August, this trend continues as the low-resistivity zone extends to the bottom of the tomogram (∼ 10 m depth). The upper part of the profile (∼ x = 0–18 m) is unaffected by the trend. A high-resistivity body of ≥ 32 kΩ m remains stable during the summer month, probably due to the shielding of water infiltration through the cable car station and consequent desiccation of the surface rock layer, combined with an intact rock mass without major fractures. Coinciding with the freezing period from September to December 2013, high electrical resistivity values reappeared (≥ 128 kΩ m).

Figure 7Tomograms of repeated ERT measurements from February to June 2013, June to September 2023, and September to December 2013, revealing seasonal resistivity changes. The position of borehole B2 is indicated in the resistivity profiles for 2023, with horizontal lines representing the 0 °C threshold on the date of the ERT measurements. The central polar plot illustrates rock temperature recorded in borehole B2 from January–December 2023, indicating measurement depths by dashed lines. Thermal anomalies (abrupt temperature changes) found in both boreholes over the entire observation period (2016–2023) are marked at the respective time and depth.

The general shift towards lower resistivity values from June to September is also clearly discernible in the raw data (Fig. B2). The median values of the apparent resistivities decreased from 15.6 kΩ m in June 2023 to 5.5 kΩ m in July and remained at low levels from August (4.0 kΩ m) to September (3.4 kΩ m). Pre-processed data from ERT measurements in June (2013 and 2023) show comparable characteristics with a wide range of apparent resistivity values and a reasonable number of data points above 19 kΩ m (i.e. laboratory threshold of frozen conditions). From July to September, apparent resistivities greater than 19 kΩ m occurred sporadically at shallow depths, whereas values characteristic for unfrozen conditions (< 10 kΩ m) are more pronounced and were observed solely in deep-penetrating measurements.

4.3 Temperature–resistivity laboratory calibration

Figure 3b shows the rock temperature related to the measured electrical resistivity of the laboratory analysis. Warming of the frozen rock samples (n = 7) starting at −3 °C followed linear temperature–resistivity behaviour with a steep gradient of −44.9 ± 12.0 kΩ m °C−1 up to the equilibrium melting point between −0.4 and 0.2 °C. The resistivity values at the equilibrium melting point ranged from 10–19 kΩ m, which is subsequently used as a threshold for the transition zone between frozen and unfrozen conditions for the inverted tomograms of the Kitzsteinhorn rock face. The unfrozen temperature–resistivity paths exhibit a flatter gradient of −0.6 ± 0.2 kΩ m °C−1. The fitting parameters and respective R2 of the curves are listed in Table D1.

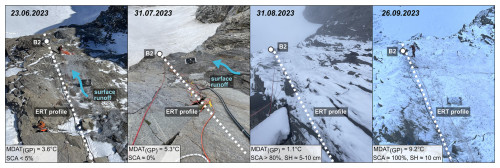

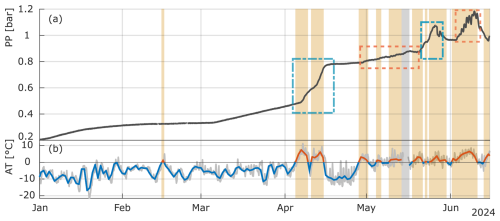

4.4 Piezometric pressure

The piezometric pressure showed a slight increase from 0.21 to 0.49 bar between January and early April in 2024 (Fig. 8). This was followed by intervals of rapid increase during spring and summer: from 0.49 to 0.78 bar in mid-April, from 0.87 to 1.07 bar at the end of May, and from 0.97 to a peak value of 1.18 bar in June. The rapid rise in piezometric pressure correlates with days when the mean air temperature was above 0 °C, as measured at the nearby Gletscherplateau weather station in 10 min intervals (2940 m a.s.l.). Notable daily fluctuations in the piezometric signal were observed from early May to mid-May and in June.

Figure 8(a) Piezometer pressure (PP) from January to June 2024 recorded near the summit station at a depth of 16.85 m. (b) Mean daily air temperature (AT) from the Gletscherplateau weather station (2940 m a.s.l., distance ∼ 500 m), shown in blue (< 0 °C) and red (> 0 °C). The moving mean air temperature (AT) over a 2 h interval is represented in grey. Yellow bars indicate periods when the mean daily air temperature was > 0 °C, during which increases (blue rectangle) and short-term fluctuations with a 24 h frequency (orange rectangle) in the pressure level were mostly observed. The grey balk marks a data gap in the weather station recordings.

5.1 Pressurised water flow in permafrost rockwalls

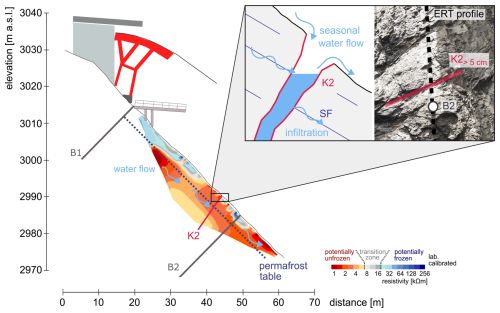

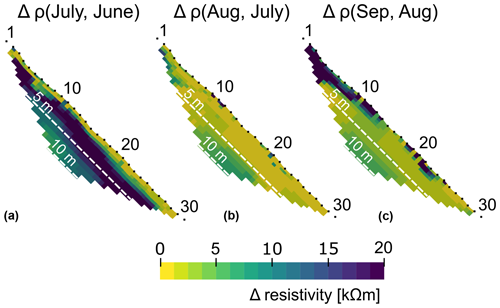

The unique time series of laboratory-calibrated ERT observations presented in this study enable a quantitative interpretation of seasonal changes in frozen rockwalls. High-resistivity sections above 19 kΩ m indicate frozen conditions with air-/ice-filled joints during the frost season (October–May). Slight warming of the rock surface after the snow cover disappears in late spring is indicated by decreasing resistivity at shallow depth (e.g. tomography from June 2023 in Fig. 7). Ice-filled joints probably act as an aquitard, constraining deep infiltration into the joint system, with snowmelt mainly draining along the rock surface. From June to July, rapid changes in resistivity of more than 1 order of magnitude were observed at ∼ 1–7 m depth, coincident with a borehole temperature warming accompanied by active-layer deepening from 1.7 to 2.7 m depth between the ERT measurement dates in June and July (Fig. 9a). The low-resistivity zone (∼ 4 kΩ m) in July in the lower part of the tomogram (∼ x = 28–58 m) gradually expands to higher rock slope sections (Fig. 7) and to the bottom of the ERT profile until September (∼ 10 m depth, Fig. 9a), while the 0 °C and −0.5 °C isotherm (i.e. permafrost table) changes marginally (August: 3.5 and 4.1 m, September: 3.5 and 4.3 m, Fig. 9a).

Figure 9(a) Median resistivity values of the ERT measurements from June–September 2023, respectively, over the depth of the inverted blocks and the corresponding temporal evolution of the 0 °C and −0.5 °C measurements observed in B2. Isotherms were calculated using average temperatures at 0.1 m depth over 3 d to minimise short-term fluctuations. (b) The temperature–resistivity relation of the field and laboratory ERT measurements showed a decrease in resistivity values from ∼ −2 to 3 °C obtained between July and September.

The term “pressurised” here refers to a piezometric head of a few metres. The rapid resistivity decline observed suggests pressurised nature of water flow in fractures, supported by additional evidence. This evidence comprises visually observed water outflow from fractures (Fig. 10) and the first piezometric measurements showing rapidly increasing pressure levels in the thawing season, with piezometric heads reaching up to 11.8 m (Fig. 8). Without assuming pressurised flow, the decline in electrical resistivity from July to September (Figs. 7, 9) would be inconsistent with Archie's law. In thawed conditions, resistivity decreases for various rock types at a rate of ∼ 2.9 ± 0.3 % °C−1 (Krautblatter, 2009) and, according to our laboratory calibrations, by 4.5 ± 0.3 % °C−1 (Fig. 3, Table D1). Thus and considering Archie's law, a temperature warming from July to September (Fig. 9) in already fully saturated rock with constant porosity would not cause a significant further and rapid electrical resistivity decline. This can only occur if pressurised water flow contributes to an additional hydraulic opening of fractures within days to weeks. In addition, the coincident rapid changes (Fig. 5) and regime changes in rock temperature (Fig. 6) cannot be explained solely by diffusive heat exchange (Noetzli et al., 2007; Krautblatter et al., 2010), but rather with water flow in open fractures (Phillips et al., 2016), facilitating a thermal shortcut between the atmosphere and the subsurface (Hasler et al., 2011a).

We hypothesise that water from snowmelt infiltrates in early summer along local joints and fractures. Joint set K2, which dips steeply to the SW (Fig. 1), may play a particularly prominent role. K2 extends perpendicularly to the dip direction of the studied rock slope, effectively collecting surface runoff and diverting it into the subsurface. There, it is most likely redistributed along the schistosity of the local calcareous mica schists, i.e. through open, surface-parallel joints that drain the infiltrated water to the base of the rock slope. This hypothesis provides a plausible explanation for the observed development of a low-resistivity zone in the lower half of the ERT tomogram in July, in which water seeps through one of the prominent K2 joints with apertures around 5 cm (Fig. 10) and is then drained downslope and pressurised upslope along the schistosity in August and September. In addition to snowmelt, rainfall events can contribute to infiltration, potentially leading to short-term warming in the subsurface related to non-conductive heat fluxes and decreased resistivity. No rainfall has been registered in the days leading up to or during the ERT data acquisitions (Fig. A1), so modifications of the hydrological regime through precipitation are not discussed here.

Figure 10Conceptual illustration of water infiltration and flow along the schistosity (SF) and geotechnical discontinuities (e.g. fracture K2 with an aperture of > 5 cm) using the ERT measurement from September 2023. Permafrost table is derived from temperature measurements at borehole B2.

The results of this study underline the large impact of fluid flow in fractures on hydrological and thermal processes in alpine permafrost rockwalls. Due to its complexity and a lack of knowledge, thermal models of permafrost distribution have often neglected the hydrology of rockwalls (e.g. Duvillard et al., 2021a; Etzelmüller et al., 2022) or have relied on an assumption of weathered zones and high porosity to represent fracture density (e.g. Noetzli et al., 2007; Magnin et al., 2017), which do not fully describe the main effects of a fracture network on permeability characteristics in low-porosity rock (Hsieh, 1998). However, fluid flow in fractures is often decisive for rapid changes in a permafrost distribution in rockwalls as already shown by geophysical measurements (Krautblatter and Hauck, 2007; Krautblatter et al., 2010; Keuschnig et al., 2017), numerical approaches (Magnin and Josnin, 2021), and our combined analysis of long-term ERT monitoring and borehole temperatures. As evidenced by several rapid drops in rock temperature recorded at the Kitzsteinhorn and at the Gemsstock borehole in Switzerland (Phillips et al., 2016), we suggest that fractures can act as cooling pathways, favouring the formation of freezing corridors and air ventilation. Ice-filled fractures initially cool the surrounding rock mass and prevent warm-water infiltration. Still, as the melting of the basal ice layer begins, thaw corridors are formed, which initiate rapid non-conductive warming in spring and summer. Cooling in autumn and winter, on the other hand, is controlled by slow conductive heat transport and contributes to the persistence of relatively warm areas at larger depths. Beside the possibility of varying subsurface thermal conductivity (Hasler et al., 2011b), this water-flow-induced seasonal succession of rapid warming and slow cooling can result in a positive thermal offset, as observed in B1 and B2 (Fig. 4a), which, over long time periods, results in bottom-up-oriented permafrost degradation.

5.2 Limitations and uncertainties

Borehole temperature measurements are vulnerable to lightning strikes, leading to sporadic thermistor failures, as has happened at several depths (0.5, 7, 10, 20, 25 m) in B2 between 2017–2023. Therefore, the frequency of thermal anomalies recorded in B2 may be underrepresented. The overall record of thermal anomalies, however, derived from a 7-year dataset (2016–2023) and at numerous depths (B1: 2; 3, 5, 7, 10, 15 m; B2: 2, 3, 5 m), still holds high significance. The system used for borehole temperature measurement facilitates direct physical contact between sensors and ambient rock mass and is, therefore, ideally suited to record short-term temperature changes. However, despite their high sensitivity, the measured thermal signals are assumed to be considerably damped compared to direct temperature measurements in fractures or cracks. Actual temperature jumps induced by water flow in fractures are expected to be significantly higher than the ones measured inside B1 and B2.

Sources of error in geophysical models are associated with data acquisition and subsequent inversion. Keuschnig et al. (2017) indicated that wind gusts, especially above 10 m s−1, might induce measurement errors. Here, we only used ERT measurements from 2013 and 2023, carried out during periods with wind speeds below 10 m s−1, making additional pre-filtering superfluous. Unfortunately, the ERT measurements in 2023 could not be repeated with the same instrument as in 2013, which might affect the comparability of the datasets (Table B1). However, the overlapping observations in June showed comparable trends in electrical resistivity towards lower values, particularly in the lower part of the profile, suggesting only a minimal influence of the different instruments. Atmospheric conditions vary slightly between years, affecting the timing of snowmelt and hence the change in the resistivity regime. The ERT results from June 2013 exhibit higher resistivity values in the upper part of the profile (> 64 kΩ m) compared to the ERT measurement in 2023 (Fig. 7), probably due to colder rock and atmospheric conditions prior to the measurement (Fig. A1). The penetration depth of the current flow into the subsurface depends on the characteristics of the top layer and may vary seasonally. Dry and frozen conditions can impede current flow, while water-saturated conditions might trap current flow, resulting in an attenuated current flow into deeper layers (Loke, 2022). Poor electrode coupling is often associated with frozen conditions and ice-filled fractures and cracks from autumn to spring, which cause noisy data and can lead to inversion artefacts represented by a high RMS error. This phenomenon was observed, for example, in September 2013 vs. 2023, where cold air temperatures likely caused freezing of the rock surface layer prior to the ERT measurement (Fig. A1), resulting in high contact resistance (Table B1) and an inability to resolve the long-lasting summer thermal signal at greater depths. Consequently, we refrained from a detailed interpretation of the inverted tomograms from February–May 2013 and September–December 2013 but included the ERT data to cover all seasons. We assume that a repeat of the ERT measurements in 2023 during the frost period would have yielded comparable results, as borehole temperature shows frozen subsurface conditions from January–June and from October–December 2023 (Fig. 7), during which no thermal anomalies or irregularities were observed (Fig. 5). In addition, we analysed the raw data from June–September 2023 to exclude an inappropriate choice of inversion parameters, even though the tomograms exhibit a marginal RMS error of less than 4.3 %. The apparent resistivity values indicate a decreasing trend over the summer (Fig. B2), consistent with the patterns shown by the respective inverted tomograms.

Laboratory calibrations are commonly applied to enable a quantitative interpretation of ERT monitoring in permafrost bedrock. We carried out laboratory ERT measurements on unfrozen and frozen mica-schist rock samples, representative of the homogeneous lithology of the study side, with only a scaly band of serpentinite at a depth of approximately 15 m according to optical borehole scans. As the ERT measurements at the north flank reached a maximum penetration depth of around 10 m, serpentinite probes were not included in the laboratory experiments. A bilinear description of the temperature–resistivity relation was preferred over an exponential behaviour of resistivity values below the freezing point, which is less appropriate for low-porosity bedrock (Krautblatter et al., 2010) compared to freezing in unconfined space (e.g. debris) and requires more unknown input parameters (Duvillard et al., 2021a). Our results suggest frozen conditions above 19 kΩ m and a frozen temperature–resistivity gradient of 44.9 ± 12.0 kΩ m °C−1, comparable to laboratory calibrations of rocks with different lithologies (Krautblatter et al., 2010; Magnin et al., 2015; Scandroglio et al., 2021; Etzelmüller et al., 2022). However, the problem of extrapolating from laboratory experiments to field observations (Zisser et al., 2007; Krautblatter et al., 2010) was highlighted by our ERT observation of the highly fractured rock face with anisotropic characteristics, which indicated the strong influence of water-saturated fractures and cracks on the electrical properties, less represented by the intact rock mass of the laboratory studies.

5.3 Implications for rockwall instabilities and permafrost monitoring

Understanding water flow in fractured permafrost rocks is challenging but crucial to improving process knowledge of permafrost dynamics. The interaction between fracture fills of air, water, and ice and the surrounding bedrock results in complex thermal patterns that strongly influence permafrost evolution and have further implications for the mechanical rock regime.

High, seasonally varying displacement rates of rock slope instabilities (Wirz et al., 2014; Mamot et al., 2021; Etzelmüller et al., 2022) and irreversible fracture displacements in summer (Weber et al., 2017) have already been linked to thawing-related processes such as meltwater infiltration in cracks and fractures. Induced hydraulic and/or hydrostatic pressures may induce uplift, which reduces the effective normal stress and thus the shear resistance (Wyllie, 2017) and can contribute as a triggering factor to slope failures in alpine rocks (Fischer et al., 2010; Walter et al., 2020; Kristensen et al., 2021). Our results show that repeated ERT monitoring can detect water infiltration and is, therefore, a promising approach to identifying periods with high hydrostatic pressure relevant to slope stability assessment.

Temperature regime changes and abrupt temperature changes recorded in B1 and B2, mainly during periods of subzero temperature (Fig. C1), indicate non-conductive heat fluxes. These sudden push-like events can transport heat from the surface to greater depths more rapidly than slow thermal conduction, which is consistent with laboratory experiments by Hasler et al. (2011a). The induced temperature rise may lead to slope destabilisation, as warming and thawing processes alter the shear resistance of ice-filled rock joints (Gruber and Haeberli, 2007; Mamot et al., 2018) and affect the rock–ice mechanics of permafrost slopes (Krautblatter et al., 2013).

The role of water flow in permafrost rockwalls is rarely investigated and remains a key challenge. This study proposes an approach to infer water flow in bedrock permafrost by combining monthly repeated electrical resistivity monitoring, long-term temperature measurements in deep boreholes, and piezometer observations. The following conclusions are drawn:

-

A massive decrease in electrical resistivity values during the thawing season (July–September) can be indicative for snowmelt water infiltration into the rockwall draining along the schistosity and interconnected joints and subsequently becoming pressurised within a widespread fracture network.

-

Hydrostatic pressure levels of up to 11.8 m indicate widespread water infiltration into the fracture network, which potentially alters slope stability by favouring bottom-up permafrost degradation.

-

Small, abrupt temperatures anomalies registered in the two boreholes (2, 3, and 5 m depth) suggest non-conductive heat flux in fractures. Frozen rock is warmed more rapidly by these sudden push-like events of heat transport from the surface than by slow thermal conduction alone.

-

Long-term regime temperature changes were identified in two boreholes in 10 and 15 m depth between 2016–2019 and 2020–2022, indicating the pronounced heat transfer by infiltrating water.

-

Monitoring of alpine permafrost often relies solely on annually repeated geoelectric measurements, mainly due to complicated logistics and harsh measurement conditions. However, our study suggests that more frequent ERT measurement intervals are required to decipher the complexity of hydrothermal processes in permafrost rockwalls and fully assess the rate and extent of permafrost evolution. Monthly repeated measurements of this contribution represent a significant advancement compared to annual surveys.

-

We emphasise the key role of complementary temperature measurements and their joint analysis. Low electrical resistivity values in the absence of borehole temperatures may be misinterpreted as permafrost-free rock slopes, whereas they could instead be an indicator of water-saturated conditions above a potential permafrost body.

This study has broad implications for understanding hydrothermal processes in steep, fractured rockwalls, which profoundly impact the rate and extent of permafrost degradation and related hazards. Future developments are needed to validate and quantify our observations. Of particular interest would be simultaneous electrical resistivity and piezometric measurements during the thawing season, whereby daily or hourly observation intervals would represent another significant step towards a better understanding of the transient nature of water flow in fractures.

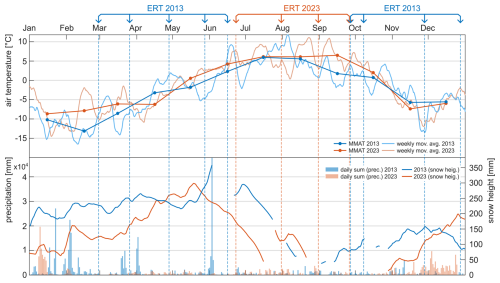

Figure A1Mean monthly air temperature (MMAT) and the weekly moving average for the air temperature for 2013 and 2023 were recorded at the nearby Gletscherplateau weather station at 2940 m a.s.l. (∼ 500 m distance from the study site). The MMAT in 2013 and 2023 showed comparable values for most months (ΔMMAT < 2.5 °C), with notable differences in February (2013: −13.1 °C; 2023: −7.9 °C), April (2013: −3.2 °C; 2023: −6.2 °C), and September (2013: 1.8 °C; 2023: 6.5 °C). Snow height was also recorded at the Gletscherplateau weather station. Although the slope angle at the weather station is lower than that surrounding the study site, the orientation is the same, making the snow height trends and subsequent snowmelt infiltration patterns transferable to the study site, although the absolute values are not. Snow height in 2013 and 2023 is visualised with a solid line, with interruptions due to data gaps. The snowmelt was most pronounced in late May 2013 and in June 2023. The bar plot shows the daily rainfall sum at the Alpincenter weather station (2450 m a.s.l., distance < 2 km). Notably, no heavy rainfall events were registered shortly before or on the days of ERT measurements.

ERT is a non-invasive geophysical method for detecting and monitoring the distribution and properties of permafrost: an electric current is injected into the subsurface by two electrodes, and the resultant electrical potential difference is measured at two other electrodes. The respective apparent resistivity of the electrical field is then determined by the injected current, the measured potential difference, and a geometric factor. The investigation depth depends on the electrode spacing, with shorter spacing resulting in a lower depth of investigation but higher resolution near the surface. The apparent resistivity values need to be inverted using an appropriate algorithm to provide areal information on the electrical resistivity distribution. Ice-filled joints and frozen or dry bedrock are typically characterised by high electrical resistivity, whereas unfrozen conditions and high liquid water content are associated with low electrical resistivity (Hauck, 2002).

Figure B1Short-term variations in apparent resistivity during repeated ERT measurements (June–September 2023) over a 24 h period. (a) Median apparent resistivity values indicate relatively stable conditions over an observation period, which is additionally supported by (b) the maximum difference in apparent resistivity of respective data points (n=135) over repeated ERT measurements, mostly less than 2 kΩ m.

Figure B2Statistical box plots with jitter data points of the apparent resistivity of the ERT measurements in June 2013 and from June–September 2023 with respect to the distance between the electrodes. It should be noted that as the electrode spacing factor increases, fewer values are measured. The electrical resistivity values indicated a general shift towards lower resistivity values from June–September.

Figure B3Difference in resistivity between tomograms observed from (a) June–July, (b) July–August, and (c) August–September in 2023. Significant decreases in electrical resistivity values are evident at greater depths (∼ 2–7 m) between June–July, while resistivity values remain relatively stable with only slight changes (< 10 kΩ m) between July–September.

Table B1Detailed information on the ERT measurement procedures and inversion routines. ERT measurements were carried out at the end of each month, except in October due to technical issues. Although different instruments were used in 2013 and 2023, which could slightly impact the comparability of datasets, the overlapping ERT measurements in June showed comparable trends in electrical resistivities towards lower values, suggesting minimal influence from the different devices. During the frost period, contact resistances were > 200 kΩ, whereas during the thawing period, they were within an acceptable range, mostly < 190 kΩ. The filtering of the outliers and inversion routines were standardised across all ERT measurements.

* One measurement indicated a contact resistance of 238 kΩ.

Data will be made available on request.

MO wrote the manuscript, conducted the geophysical surveys in 2023, performed the data analysis, and designed the figures with substantial contribution from SW and MaK. MaK provided the datasets of geophysical surveys in 2013, and IH contributed borehole temperature and piezometer data. SW, MiK, and MaK supervised the study. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and improved the final version of the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

This article is part of the special issue “Emerging geophysical methods for permafrost investigations: recent advances in permafrost detecting, characterizing, and monitoring”. It is not associated with a conference.

The authors would like to thank Maximilian Rau, Felix Pfluger, Georg Stockinger, and Maximilian Reinhard for their extensive support during the fieldwork. We furthermore thank the Gletscherbahnen Kaprun AG for financial and logistical support. We are grateful to the editor, Teddi Herring, and three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Maike Offer acknowledges PhD funding from the Deutsche Bundesstiftung Umwelt (DBU). In addition, the research has been supported by the Gletscherbahnen Kaprun AG.

This paper was edited by Teddi Herring and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Archie, G. E.: The electrical resistivity log as an aid in determining some reservoir characteristics, Trans. AIME 146, 54–62, https://doi.org/10.2118/942054-G, 1942. a

Arenson, L. U., Harrington, J. S., Koenig, C. E. M., and Wainstein, P. A.: Mountain permafrost hydrology – A practical review following studies from the Andes, Geosciences, 12, 48, https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences12020048, 2022. a

Bast, A., Kenner, R., and Phillips, M.: Short-term cooling, drying, and deceleration of an ice-rich rock glacier, The Cryosphere, 18, 3141–3158, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-18-3141-2024, 2024. a

Ben-Asher, M., Magnin, F., Westermann, S., Bock, J., Malet, E., Berthet, J., Ravanel, L., and Deline, P.: Estimating surface water availability in high mountain rock slopes using a numerical energy balance model, Earth Surf. Dynam., 11, 899–915, https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-11-899-2023, 2023. a

Buckel, J., Mudler, J., Gardeweg, R., Hauck, C., Hilbich, C., Frauenfelder, R., Kneisel, C., Buchelt, S., Blöthe, J. H., Hördt, A., and Bücker, M.: Identifying mountain permafrost degradation by repeating historical electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) measurements, The Cryosphere, 17, 2919–2940, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-17-2919-2023, 2023. a

Burn, C. R. and Smith, C.: Observations of the “thermal offset” in near-surface mean annual ground temperatures at several sites near Mayo, Yukon Territory, Canada, Arctic, 41, 99–104, https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic1700, 1988. a

Cathala, M., Bock, J., Magnin, F., Ravanel, L., Ben Asher, M., Astrade, L., Bodin, X., Chambon, G., Deline, P., Faug, T., Genuite, K., Jaillet, S., Josnin, J.-Y., Revil, A., and Richard, J.: Predisposing, triggering and runout processes at a permafrost–affected rock avalanche site in the French Alps (Étache, June 2020), Earth Surf. Proc. Land., 49, 2899-3247, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.5881, 2024a. a

Cathala, M., Magnin, F., Ravanel, L., Dorren, L., Zuanon, N., Berger, F., Bourrier, F., and Deline, P.: Mapping release and propagation areas of permafrost-related rock slope failures in the French Alps: A new methodological approach at regional scale, Geomorphology, 448, 109032, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2023.109032, 2024b. a

Cimpoiasu, M. O., Kuras, O., Harrison, H., Wilkinson, P. B., Meldrum, P., Chambers, J. E., Liljestrand, D., Oroza, C., Schmidt, S. K., Sommers, P., Vimercati, L., Irons, T. P., Lyu, Z., Solon, A., and Bradley, J. A.: High-resolution 4D ERT monitoring of recently deglaciated sediments undergoing freeze-thaw transitions in the High Arctic, EGUsphere [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2024-350, 2024. a

Cornelius, H. P. and Clar, E.: Erläuterungen zur geologischen Karte des Glocknergebietes (1:25.000), Geologische Bundesanstalt – Wien III, 1935. a

Draebing, D. and Krautblatter, M.: P-wave velocity changes in freezing hard low-porosity rocks: a laboratory-based time-average model, The Cryosphere, 6, 1163–1174, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-6-1163-2012, 2012. a

Draebing, D., Krautblatter, M., and Hoffmann, T.: Thermo–cryogenic controls of fracture kinematics in permafrost rockwalls, Geophys. Res. Lett., 44, 3535–3544, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL072050, 2017. a

Duvillard, P.-A., Ravanel, L., Marcer, M., and Schoeneich, P.: Recent evolution of damage to infrastructure on permafrost in the French Alps, Reg. Environ. Change, 19, 1281–1293, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-019-01465-z, 2019. a

Duvillard, P.-A., Magnin, F., Revil, A., Legay, A., Ravanel, L., Abdulsamad, F., and Coperey, A.: Temperature distribution in a permafrost-affected rock ridge from conductivity and induced polarization tomography, Geophys. J. Int., 225, 1207–1221, https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggaa597, 2021a. a, b

Duvillard, P.-A., Ravanel, L., Schoeneich, P., Deline, P., Marcer, M., and Magnin, F.: Qualitative risk assessment and strategies for infrastructure on permafrost in the French Alps, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol., 189, 103311, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2021.103311, 2021b. a

Etzelmüller, B., Guglielmin, M., Hauck, C., Hilbich, C., Hoelzle, M., Isaksen, K., Noetzli, J., Oliva, M., and Ramos, M.: Twenty years of European mountain permafrost dynamics – the PACE legacy, Environ. Res. Lett., 15, 104070, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abae9d, 2020. a

Etzelmüller, B., Czekirda, J., Magnin, F., Duvillard, P.-A., Ravanel, L., Malet, E., Aspaas, A., Kristensen, L., Skrede, I., Majala, G. D., Jacobs, B., Leinauer, J., Hauck, C., Hilbich, C., Böhme, M., Hermanns, R., Eriksen, H. Ø., Lauknes, T. R., Krautblatter, M., and Westermann, S.: Permafrost in monitored unstable rock slopes in Norway – new insights from temperature and surface velocity measurements, geophysical surveying, and ground temperature modelling, Earth Surf. Dynam., 10, 97–129, https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-10-97-2022, 2022. a, b, c

Fischer, L., Amann, F., Moore, J. R., and Huggel, C.: Assessment of periglacial slope stability for the 1988 Tschierva rock avalanche (Piz Morteratsch, Switzerland), Eng. Geol., 116, 32–43, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2010.07.005, 2010. a, b

GEOKON: Model 4500 Series, Vibrating Wire Piezometer, Instruction Manual, https://www.geokon.com/content/manuals/4500_Piezometer.pdf (last access: 24 March 2024), 2024. a

Gruber, S. and Haeberli, W.: Permafrost in steep bedrock slopes and its temperature-related destabilization following climate change, J. Geophys. Res., 112, F02S18, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JF000547, 2007. a, b, c, d

Hartmeyer, I., Keuschnig, M., and Schrott, L.: Long-term monitoring of permafrost-affected rock faces – A scale-oriented approach for the investigation of ground thermal conditions in alpine terrain, Kitzsteinhorn, Austria, Austrian J. Earth Sc., 105, 128–139, 2012. a, b, c

Hartmeyer, I., Delleske, R., Keuschnig, M., Krautblatter, M., Lang, A., Schrott, L., and Otto, J.-C.: Current glacier recession causes significant rockfall increase: the immediate paraglacial response of deglaciating cirque walls, Earth Surf. Dynam., 8, 729–751, https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-8-729-2020, 2020. a, b, c

Hasler, A., Gruber, S., Font, M., and Dubois, A.: Advective heat transport in frozen rock clefts: conceptual model, laboratory experiments and numerical simulation, Permafrost Periglac., 22, 378–389, https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp.737, 2011a. a, b, c

Hasler, A., Gruber, S., and Haeberli, W.: Temperature variability and offset in steep alpine rock and ice faces, The Cryosphere, 5, 977–988, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-5-977-2011, 2011b. a, b

Hauck, C.: Frozen ground monitoring using DC resistivity tomography, Geophys. Res. Lett., 29, 12-1–12-4, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002GL014995, 2002. a, b, c

Hauck, C. and Kneisel, C. (Eds.): Applied geophysics in periglacial environments, Cambirge University Press, ISBN 9780511535628, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511535628, 2008. a

Herring, T., Lewkowicz, A. G., Hauck, C., Hilbich, C., Mollaret, C., Oldenborger, G. A., Uhlemann, S., Farzamian, M., Calmels, F., and Scandroglio, R.: Best practices for using electrical resistivity tomography to investigate permafrost, Permafrost Periglac., 34, 494–512, https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp.2207, 2023. a, b

Hilbich, C.: Time-lapse refraction seismic tomography for the detection of ground ice degradation, The Cryosphere, 4, 243–259, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-4-243-2010, 2010. a

Hilbich, C., Hauck, C., Mollaret, C., Wainstein, P., and Arenson, L. U.: Towards accurate quantification of ice content in permafrost of the Central Andes – Part 1: Geophysics-based estimates from three different regions, The Cryosphere, 16, 1845–1872, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-16-1845-2022, 2022. a

Hoeck, V., Pestal, G., Brandmaier, P., Clar, E., Cornelius, H., Frank, W., Matl, H., Neumayr, P., Petrakakis, K., Stadlmann, T., and Steyrer, H.: Geologische Karte der Republik Österreich, Blatt 153 Großglockner, Geologische Bundesanstalt, Vienna, 1994. a

Hsieh, P. A.: Scale effects in fluid flow through fractured geologic media, in: Scale dependence and scale invariance in hydrology, edited by: Sposito, G., Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 335–353, ISBN 9780521571258, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511551864.013, 1998. a

Keuschnig, M., Hartmeyer, I., Otto, J.-C., and Schrott, L.: A new permafrost and mass movement monitoring test site in the Eastern Alps – Concept and first results of the MOREXPERT project. In Managing Alpine Future II (Vol. IGF-Forschungsberichte, 4, Verlag der Osterreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 163–173, 2011. a

Keuschnig, M., Krautblatter, M., Hartmeyer, I., Fuss, C., and Schrott, L.: Automated electrical resistivity tomography testing for early Warning in unstable permafrost rock walls around alpine infrastructure, Permafrost Periglac., 28, 158–171, https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp.1916, 2017. a, b, c, d, e, f

Krautblatter, M.: Detection and quantification of permafrostchange in alpine rock walls and implications for rock instability, dissertation, Friedrich-Wilhelms University Bonn, https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:hbz:5N-18389 (last access: 24 March 2024), 2009. a

Krautblatter, M. and Hauck, C.: Electrical resistivity tomography monitoring of permafrost in solid rock walls, J. Geophys. Res., 112, F02S20, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JF000546, 2007. a, b, c

Krautblatter, M., Verleysdonk, S., Flores-Orozco, A., and Kemna, A.: Temperature-calibrated imaging of seasonal changes in permafrost rock walls by quantitative electrical resistivity tomography (Zugspitze, German/Austrian Alps), J. Geophys. Res., 115, F02003, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JF001209, 2010. a, b, c, d, e, f, g

Krautblatter, M., Funk, D., and Günzel, F. K.: Why permafrost rocks become unstable: a rock-ice-mechanical model in time and space, Earth Surf. Proc. Land., 38, 876–887, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.3374, 2013. a, b, c

Kristensen, L., Czekirda, J., Penna, I., Etzelmüller, B., Nicolet, P., Pullarello, J. S., Blikra, L. H., Skrede, I., Oldani, S., and Abellan, A.: Movements, failure and climatic control of the Veslemannen rockslide, Western Norway, Landslides, 18, 1963–1980, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-020-01609-x, 2021. a

Krus, M.: Feuchtetransport und Speicherkoeffizienten poröser mineralischer Baustoffe, Theoretische Grundlagen und neue Meßtechniken, dissertation, University of Stuttgart, Faculty of Civil and Environmental Engineering, 1995. a

Loke, M. H.: Tutorial: 2-D and 3-D electrical imaging surveys, https://www.geotomosoft.com/ (last access: 24 March 2024), 2022. a

Loke, M. H. and Barker, R. D.: Rapid least–squares inversion of apparent resistivity pseudosections by a quasi–Newton method, Geophys. Prospect., 44, 131–152, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2478.1996.tb00142.x, 1996. a

Magnin, F. and Josnin, J.-Y.: Water flows in rock wall permafrost: A numerical approach coupling hydrological and thermal processes, J. Geophys. Res.-Earth, 126, e2021JF006394, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JF006394, 2021. a, b

Magnin, F., Krautblatter, M., Deline, P., Ravanel, L., Malet, E., and Bevington, A.: Determination of warm, sensitive permafrost areas in near–vertical rockwalls and evaluation of distributed models by electrical resistivity tomography, J. Geophys. Res.-Earth, 120, 745–762, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JF003351, 2015. a

Magnin, F., Josnin, J.-Y., Ravanel, L., Pergaud, J., Pohl, B., and Deline, P.: Modelling rock wall permafrost degradation in the Mont Blanc massif from the LIA to the end of the 21st century, The Cryosphere, 11, 1813–1834, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-11-1813-2017, 2017. a

Mamot, P., Weber, S., Schröder, T., and Krautblatter, M.: A temperature- and stress-controlled failure criterion for ice-filled permafrost rock joints, The Cryosphere, 12, 3333–3353, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-12-3333-2018, 2018. a, b

Mamot, P., Weber, S., Lanz, M., and Krautblatter, M.: Brief communication: The influence of mica-rich rocks on the shear strength of ice-filled discontinuities, The Cryosphere, 14, 1849–1855, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-14-1849-2020, 2020. a

Mamot, P., Weber, S., Eppinger, S., and Krautblatter, M.: A temperature-dependent mechanical model to assess the stability of degrading permafrost rock slopes, Earth Surf. Dynam., 9, 1125–1151, https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-9-1125-2021, 2021. a

Mergili, M., Jaboyedoff, M., Pullarello, J., and Pudasaini, S. P.: Back calculation of the 2017 Piz Cengalo–Bondo landslide cascade with r.avaflow: what we can do and what we can learn, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 20, 505–520, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-20-505-2020, 2020. a

Mollaret, C., Hilbich, C., Pellet, C., Flores-Orozco, A., Delaloye, R., and Hauck, C.: Mountain permafrost degradation documented through a network of permanent electrical resistivity tomography sites, The Cryosphere, 13, 2557–2578, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-13-2557-2019, 2019. a

Noetzli, J., Gruber, S., Kohl, T., Salzmann, N., and Haeberli, W.: Three–dimensional distribution and evolution of permafrost temperatures in idealized high–mountain topography, J. Geophys. Res., 112, F02S13, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JF000545, 2007. a, b

Outcalt, S. I., Nelson, F. E., and Hinkel, K. M.: The zero–curtain effect: Heat and mass transfer across an isothermal region in freezing soil, Water Resour. Res., 26, 1509–1516, https://doi.org/10.1029/WR026i007p01509, 1990. a

Phillips, M., Haberkorn, A., Draebing, D., Krautblatter, M., Rhyner, H., and Kenner, R.: Seasonally intermittent water flow through deep fractures in an alpine rock ridge: Gemsstock, Central Swiss Alps, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol., 125, 117–127, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2016.02.010, 2016. a, b, c

Phillips, M., Buchli, C., Weber, S., Boaga, J., Pavoni, M., and Bast, A.: Brief communication: Combining borehole temperature, borehole piezometer and cross-borehole electrical resistivity tomography measurements to investigate seasonal changes in ice-rich mountain permafrost, The Cryosphere, 17, 753–760, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-17-753-2023, 2023. a

Pogrebiskiy, M. and Chernyshev, S.: Determination of the permeability of the frozen fissured rock massif in the vicinity of the Kolyma hydroelectric power station, Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory – Draft Translation, 634, 1–13, 1977. a

Ravanel, L., Magnin, F., and Deline, P.: Impacts of the 2003 and 2015 summer heatwaves on permafrost-affected rock-walls in the Mont Blanc massif, Sci. Total Environ., 609, 132–143, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.07.055, 2017. a, b

Sass, O.: Die Steuerung von Steinschlagmenge durch Mikroklima, Gesteinsfeuchte und Gesteinseigenschaften im westlichen Karwendelgebirge (Bayrische Alpen), Münch. Geogr. Abh., B29, 1–175, 1998. a

Savi, S., Comiti, F., and Strecker, M. R.: Pronounced increase in slope instability linked to global warming: A case study from the eastern European Alps, Earth Surf. Proc. Land., 46, 1328–1347, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.5100, 2021. a

Scandroglio, R., Draebing, D., Offer, M., and Krautblatter, M.: 4D quantification of alpine permafrost degradation in steep rock walls using a laboratory–calibrated electrical resistivity tomography approach, Near Surface Geophys., 19, 241–260, https://doi.org/10.1002/nsg.12149, 2021. a, b

Schneider, S., Daengeli, S., Hauck, C., and Hoelzle, M.: A spatial and temporal analysis of different periglacial materials by using geoelectrical, seismic and borehole temperature data at Murtèl–Corvatsch, Upper Engadin, Swiss Alps, Geogr. Helv., 68, 265–280, https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-68-265-2013, 2013. a

Schober, A., Bannwart, C., and Keuschnig, M.: Rockfall modelling in high alpine terrain – validation and limitations/Steinschlagsimulation in hochalpinem Raum – Validierung und Limitationen, Geomechanics and Tunnelling, 5, 368–378, https://doi.org/10.1002/geot.201200025, 2012. a

Schrott, L., Otto, J.-C., and Keller, F.: Modelling alpine permafrost distribution in the Hohe Tauern region, Austria, Austrian J. Earth Sc., 105, 169–183, 2012. a

Telford, W. M., Geldart, L. P., and Sheriff, R. E.: Applied geophysics, Cambridge Univ. Pr, Cambridge, 2nd Edn., ISBN 0521339383, 2004. a

Wagner, F. M., Mollaret, C., Günther, T., Kemna, A., and Hauck, C.: Quantitative imaging of water, ice and air in permafrost systems through petrophysical joint inversion of seismic refraction and electrical resistivity data, Geophys. J. Int., 219, 1866–1875, https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggz402, 2019. a