the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Evidence of active subglacial lakes under a slowly moving coastal region of the Antarctic Ice Sheet

Jennifer F. Arthur

Calvin Shackleton

Geir Moholdt

Kenichi Matsuoka

Jelte van Oostveen

Active subglacial lakes beneath the Antarctic Ice Sheet provide insights into the dynamic subglacial environment, with implications for ice-sheet dynamics and mass balance. Most previously identified lakes have been found upstream (>100 km) of fast-flowing glaciers in West Antarctica, and none have been found in the coastal region of Dronning Maud Land (DML) in East Antarctica. The regional distribution and extent of lakes as well as their timescales and mechanisms of filling–draining activity remain poorly understood. We present local ice surface elevation changes in the coastal DML region that we interpret as unique evidence of seven active subglacial lakes located under slowly moving ice near the grounding line margin. Laser altimetry data from ICESat-2 and ICESat (Ice, Cloud, and Land Elevation Satellites) combined with multi-temporal Reference Digital Elevation Model of Antarctica (REMA) strips reveal that these lakes actively fill and drain over periods of several years. Stochastic analyses of subglacial water routing together with visible surface lineations on ice shelves indicate that these lakes discharge meltwater across the grounding line. Two lakes are within 15 km of the grounding line, while another three are within 54 km. Ice flows 17–172 m a−1 near these lakes, much slower than the mean ice flow speed near other active lakes within 100 km of the grounding line (303 m a−1). Our results improve knowledge of subglacial meltwater dynamics and evolution in this region of East Antarctica and provide new observational data to refine subglacial hydrological models.

- Article

(10374 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(2025 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Hydrologically active subglacial lakes periodically store and release water beneath the Antarctic Ice Sheet and form a key component of the basal hydrological system. Active lakes are known to influence the dynamics of the overlying ice by reducing basal friction and periodically triggering short-term acceleration in ice flow (Stearns et al., 2008; Siegfried et al., 2016; Siegfried and Fricker, 2018; Andersen et al., 2023). Temporary acceleration in ice flow of up to ∼ 10 % has been linked to lake drainage events on Byrd Glacier, East Antarctica (Stearns et al., 2008); on Crane Glacier on the Antarctic Peninsula (Scambos et al., 2011); and on the Mercer and Whillans ice streams, West Antarctica (Siegfried et al., 2016). Individual active subglacial lakes can range from ∼ 5 km2 to thousands of square kilometres and have been shown to form connected networks over hundreds of kilometres (Fricker et al., 2007; Fricker and Scambos, 2009; Smith et al., 2009; Flament et al., 2014; Siegfried and Fricker, 2018; Hodgson et al., 2022; Livingstone et al., 2022). Downstream subglacial water flow has been linked to cascading lake drainage events that transport excess water episodically towards the grounding line (Flament et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2017; Siegfried and Fricker, 2018; Neckel et al., 2021). Meltwater outlets at the grounding line discharge freshwater into sub-ice-shelf cavities, which, according to models, could enhance ice-shelf basal melting (Carter and Fricker, 2012; Dow et al., 2022) and reduce sea-ice volume (Goldberg et al., 2023) and has also been shown to influence sediment fluxes (Lepp et al., 2022) and biogeochemical fluxes (Wadham et al., 2013). Therefore, observing active lakes using repeated satellite data is crucial to characterize subglacial hydrology and its impact on the ice-sheet–ocean system.

Over the past 2 decades, over 140 active subglacial lakes have been detected underneath the Antarctic Ice Sheet using satellite data (Fig. 1; Neckel et al., 2021; Livingstone et al., 2022). Satellite radar and laser altimetry (e.g. ESA's CryoSat-2 and NASA's Ice, Cloud, and Land Elevation Satellites (ICESat and ICESat-2)) has successfully been used to identify localized ice surface elevation changes on annual to decadal timescales, interpreted as subglacial lake filling and draining activity and corresponding changes in lake volume (e.g. Fricker et al., 2007, 2010; Smith et al., 2009). Even finer patterns of centimetre-scale ice surface elevation changes have been identified using differential synthetic aperture radar interferometry (DInSAR) and interpreted as evidence for transient subglacial water transport (Gray et al., 2005; Neckel et al., 2021; Moon et al., 2022). Few active subglacial lakes have yet been reported in the coastal region of the Antarctic Ice Sheet (Livingstone et al., 2022). Specifically, only 10 active lakes have previously been identified within 50 km of the ice-sheet grounding line (Livingstone et al., 2022). Consequently, little is known about the subglacial hydrology and water routing and and the impact on local ice dynamics at the transition between grounded and floating ice in this region.

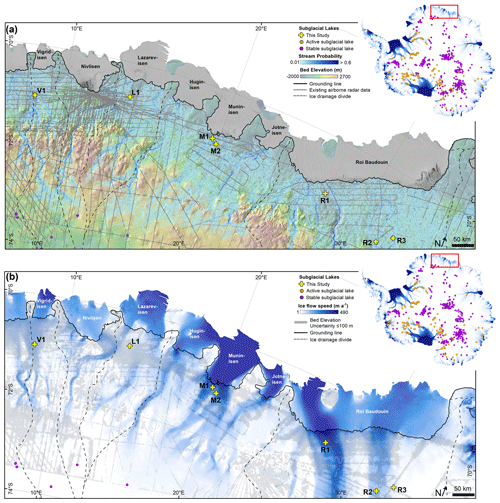

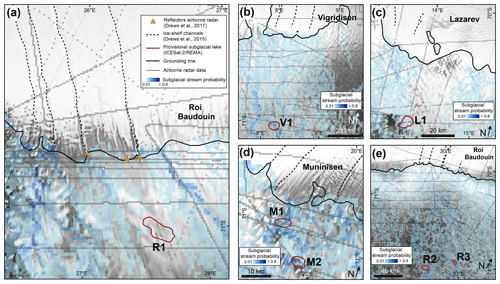

Figure 1The coastal region in Dronning Maud Land. (a) The locations of active subglacial lakes identified in this study in relation to predicted subglacial stream locations based on water routing analysis, bed topography, and regional radar data. The solid black line is the MEaSUREs grounding line (Rignot et al., 2016), bed elevations are from BedMachine (Morlighem, 2022), radar data is from Frémand et al. (2023), and the ice flow drainage divides (dashed lines) are from Mouginot et al. (2017). Subglacial lake locations on the inset maps are from Livingstone et al. (2022), where active lakes are represented by orange dots and stable lakes by purple dots. (b) Ice flow speed (Gardner et al., 2018) in blue shading and areas with bed elevation uncertainty <100 m based on the median absolute deviation between 50 bed topography simulations in this study (all other regions ≥100 m). Simulations of subglacial water drainage pathways are limited to ca. <73° S.

In this study, we build on previous work by providing a more complete inventory of active subglacial lakes inferred from measuring ice surface elevation displacement, using the laser altimeters on board ICESat-2 between March 2019 and May 2023 and on board its predecessor, ICESat, between October 2003 and March 2009. We focus on the coastal Dronning Maud Land (DML) region of East Antarctica, where no active lakes have been identified previously (Fig. 1). We use ICESat and ICESat-2 elevation time series together with strip data from the Reference Digital Elevation Model of Antarctica (REMA; Howat et al., 2019) to determine the temporal patterns of subglacial lake activity and estimate lake volume changes. We further estimate subglacial stream probability using water routing analyses derived from stochastic simulations (Shackleton et al., 2023) to assess upstream hydrological systems and potential downstream impacts of the newly observed subglacial lakes. The combination of these datasets reveals seven previously unreported active subglacial lakes that fill and drain over periods of multiple years and identifies the most probable pathways of meltwater released from lakes towards the grounding line. Our study provides insights into active subglacial hydrological systems and potential subglacial outlets in the coastal region of eastern Dronning Maud Land. This can help to better constrain how subglacial lake activity regulates ice-sheet basal conditions and ice dynamics, as well as modifies ice-shelf cavity circulation and basal melting when meltwater is released at the grounding line.

2.1 Study area

We focus on the coastal region of grounded ice in DML, extending along the Princess Astrid Coast and the Princess Ragnhild Coast up to the Roi Baudouin Ice Shelf (69 to 72° S and 33° W to 6° E; Fig. 1). There are ∼ 13 fast-flowing outlet glaciers along this coast (88–281 m a−1), which are surrounded by slowly moving ice (2–30 m a−1; Gardner et al., 2018). Grounded ice in this region of the ice sheet lies largely below the present-day sea level (Morlighem, 2022; Frémand et al., 2023; Fig. 1). Satellite altimetry from ICESat and/or ICESat-2 has recorded significant ice-sheet thickening in DML over the last 2 decades (Smith et al., 2020) due to high snowfall rates (e.g. Boening et al., 2012). So far, no active subglacial lakes have been recorded in the coastal region of DML, but ∼ 160 km inland near the onset of the Jutulstraumen Ice Stream, west of our study region, a cluster of eight ice surface subsidence and uplift events between 2017 and 2020 were identified using double-differential synthetic aperture radar interferometry (DDInSAR) and ICESat-2 altimetry (Neckel et al., 2021). These vertical movements of the ice surface reached 14.4 cm and were interpreted as episodic subglacial lake drainage events with durations between 12 d and ∼ 1 year, indicating cascading subglacial water over a ∼175 km flow path (Neckel et al., 2021). Stable subglacial lakes have also been detected in airborne ice-penetrating radar data at 33 locations in the inland of DML (Fig. 1; Goeller et al., 2016). In contrast to hydrologically active lakes that fill and drain over decadal or shorter timescales, stable subglacial lakes predominantly detected from radio-echo sounding beneath the ice-sheet interior with a warm base tend to be stable over >103-year timescales (Wright and Siegert, 2012; Livingstone et al., 2022).

2.2 Satellite altimetry

2.2.1 ICESat-2

NASA's next-generation Ice, Cloud, and Land Elevation Satellite (ICESat-2) is a photon-counting laser altimeter providing repeat-pass ice surface height measurements every 91 d (Markus et al., 2017). The Advanced Topographic Laser Altimeter System (ATLAS) on board ICESat-2 continuously profiles the Earth's surface along its 1387 reference ground tracks (RGTs) using six laser beams, which measure three pairs of tracks, with each pair separated by 3.3 km. The beams within each pair are separated by ∼ 90 m. Elevation-change data in this paper are based on release 6 of the ICESat-2 Level 3b slope-corrected land-ice height time series (ATL11) product (Smith et al., 2023a), which became available in August 2023. We used the ATL11 data spanning April 2019 to April 2023, for which the geolocation of each beam is accurately determined (Smith et al., 2023b). We omitted the ATL11 data collected between October 2018 and March 2019 because an issue with the central-beam-pair pointing resulted in displacement of ICESat-2 measured tracks from the RGTs by up to several kilometres (Smith et al., 2023b). All previous studies detecting subglacial lakes in Antarctica from ICESat-2 have used the lower-level ICESat-2 ATL06 product, which provides geolocated land-ice surface heights that are corrected for geophysical impacts and instrument bias (e.g. Siegfried and Fricker, 2021; Neckel et al., 2021; Fan et al., 2022).

A main difference between ATL06 and ATL11 is that ATL06 elevations require slope correction using a digital elevation model (DEM) or data-fitted reference surface when comparing repeat tracks, whereas this is already done as part of the ATL11 processing, directly providing time series of along-track ice surface heights that are slope corrected onto a reference pair track (RPT) for each cycle and are accurate to <0.07 m (Smith et al., 2023b; Brunt et al., 2021). In this way, ATL11 height estimates have corrected ATL06 heights for the combined effect of small cross-track offsets (up to ∼ 130 m) between repeat measurements and sub-kilometre and surface topography around fit centres. The ATL11 product has so far been used in Antarctica to assess the impact of net snow accumulation variability on observed surface height change (Medley et al., 2022) and to investigate ice-shelf basal channel morphology at the Kamb Ice Stream grounding line (Whiteford et al., 2022). Over the Greenland Ice Sheet, ATL11 has been used to evaluate spatial patterns of surface mass balance and firn densification (Smith et al., 2023b) and to investigate subglacial lake activity beneath the surface ablation zone (Fan et al., 2023).

Two types of height error estimates are provided with ATL11. One is random per-point estimates (h_corr_sigma), which include the errors related to the accuracy of the reference surface and the precision of the ICESat-2 range estimates and are uncorrelated between adjacent reference points (Smith et al., 2023b). The other is systematic error estimates (h_corr_sigma_systematic), which include the slope-dependent impact of geolocation errors that are correlated along each track. For the ICESat-2 data we analyse here, we find maximum per-point error and systematic error of 14.9 and 14.5 cm in the corrected surface heights, respectively. These maximum values are higher than the reported per-point errors of 1–2 cm in the ice-sheet interior because rougher, steeper surfaces towards the coast typically degrade the instrument precision and slope correction (Smith et al., 2023b). However, the mean per-point and systematic errors for the ICESat-2 data analysed here are still as low as 2.7 and 5.3 cm, respectively.

To investigate subglacial lake drainage and filling patterns, we followed the approach of calculating repeat-track elevation anomalies (Fricker et al., 2014; Neckel et al., 2021; Siegfried and Fricker, 2018, 2021). We first removed poor-quality surface elevations that were potentially caused by cloud cover, blowing snow, or background photon clustering, based on ATL11's overall quality summary flag (atl11_qual_summary = 0) (Siegfried and Fricker, 2021). Previous studies have calculated elevation anomalies with respect to a DEM or other reference surface (Fricker et al., 2014; Neckel et al., 2021). Using the slope-corrected ATL11, we assessed ice surface elevation changes directly with respect to the start of our observation period (April 2019) by calculating elevation anomalies (dh) for each ATL11 point along every RGT relative to the first available cycle (h0) using , where h is ice surface elevation. We calculated time series of elevation anomalies along each RGT.

2.2.2 ICESat

NASA's Ice, Cloud, and Land Elevation Satellite (ICESat) was a laser altimeter providing ice surface height measurements in footprints with a ∼ 65 m diameter separated by ∼ 172 m along its RGTs (Schutz et al., 2005; Fricker and Padman, 2006). We used the ICESat GLA12 ice-sheet product version 34, collected between February 2003 and October 2009, to derive elevation changes. ICESat RGTs were typically repeated within a ∼ 150 m cross-track distance and are vertically accurate within a few tens of centimetres depending on the surface slope (Brenner et al., 2007; Kohler et al., 2012). ICESat crossover errors (i.e. at the point where successive ascending and descending passes intersect) have been estimated between 7.5 cm for flat surfaces and 20 cm for 1° slopes (Smith et al., 2009), meaning that most errors are <15 cm in our study region, where slopes are typically <0.6° (Smith et al., 2009). The GLA12 product was used to compile the first comprehensive Antarctic inventory of 124 active subglacial lakes north of 86° S, demonstrating the short-term basal hydrologic evolution of lakes throughout Antarctica (Smith et al., 2009).

We estimated along-track elevation changes from GLA12 following the approach of Moholdt et al. (2010) by fitting surface planes to 700 m segments of repeat-track data and determining surface elevation anomalies for all laser footprints with respect to the plane fit. Outlier points with elevation anomalies >10 m, for example due to cloud scattering or rough topography, were iteratively removed in the plane-fit processing. This threshold was set higher than the expected elevation changes due to subglacial lake activity in order to not remove such data. We further neglected potential long-term elevation changes due to surface mass balance and large-scale ice dynamics in the plane fitting, as these are generally an order of magnitude smaller (Pratap et al., 2022; Goel et al., 2024) than the elevation anomalies we observe due to subglacial lake activity.

2.3 Subglacial lake detection

Previous studies have identified lakes based on thresholds between ±0.1 and 0.5 m for spatially coherent elevation anomalies using ICESat (Fricker et al., 2007, 2014; Smith et al., 2009) and Cryosat-2 (Kim et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2017; Malczyk et al., 2020). We adapted these previous approaches to our coastal study region, which is characterized by high slopes and roughness, by identifying potential areas of subglacial lake activity from ICESat/ICESat-2 repeat tracks with significant (±1 m) elevation anomalies over a distance of ≥1 km. The elevation anomaly patterns over these areas were then manually examined to assess whether these appeared to reflect lake activity (i.e. arc-shaped profiles of draining and/or filling) or if they were, for example, in highly crevassed or sloping regions where unresolved rough topography is likely to dominate the signal. We found that using a ±1 m threshold applied to elevation anomalies relative to the start of our observation period best highlighted and distinguished substantial localized anomalies from background along-track elevation changes and noise, whereas lower thresholds (e.g. ±0.5 m) included surface-elevation-change signals that are unlikely to be related to subglacial lake activity.

2.4 REMA strip differencing and lake outlines

Following the detection of ICESat-2 surface elevation anomalies, we used high-resolution stereoscopic data from REMA (Howat et al., 2019) over these locations to further investigate subglacial lake activity and spatial extents. We differenced available DEM strips with 2 m map cells acquired between September 2015 and December 2021 that intersected regions with elevation anomalies identified in ICESat/ICESat-2 data to calculate surface height changes over three suspected lakes (L1, R1, R2; Table 1). The number of useable DEM strips (i.e. partially or fully covering each lake) in any given year averaged between one and three strips per lake (Fig. S1). The DEM strips are generated by applying fully automated stereo auto-correlation techniques to overlapping pairs of high-resolution optical satellite images, using the open-source Surface Extraction from TIN-based (triangulated-irregular-network-based) Searchspace Minimization (SETSM) software (Howat et al., 2019). Individual 2 m REMA strips are not coregistered to satellite altimetry, unlike the REMA mosaic (Howat et al., 2019), meaning that relative elevation within a strip is precise but has low absolute accuracy (Hodgson et al., 2022). To increase absolute accuracy, DEM strips can be coregistered using static reference points, typically rock outcrops (Shean et al., 2019). The strips that we used do not include any outcrops, so instead we estimated and removed vertical-elevation biases using the temporally closest overlapping ICESat-2 track within ±100 d of the DEM strip acquisition date (Chartrand and Howat, 2020; Zinck et al., 2023). This time restriction ensures that the REMA elevations are representative of the strip acquisition time, although we acknowledge that some lake filling or drainage could still occur within this time period.

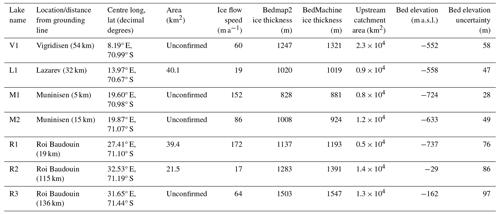

Table 1Subglacial lakes identified in this study. Lake areas are listed for those lakes where elevation anomalies were also derived from REMA strip differencing. Ice flow speed (Gardner et al., 2018), ice thickness (Fretwell et al., 2013; Morlighem, 2022), and bed elevation (Morlighem, 2022) are mean values within each inferred lake boundary. Bed elevation uncertainty is the median absolute deviation of 50 stochastic bed elevation simulations. Potential upstream catchment areas are ensemble-mean values derived from water routing analyses using the simulated bed.

Of the 10 DEM strips that intersected the 7 potential areas of subglacial lake activity we identified, 6 strips were vertically coregistered to ICESat-2 elevations (Table S1). The other four strips were not coregistered due to a lack of contemporaneous ICESat-2 data but were still included to provide further insight into the lake activity of lakes L1 and R1 (Fig. S2). In these cases, the remaining vertical biases are reflected in near-constant elevation differences outside of the active lake areas. Static lake boundaries were digitized from the pattern of elevation anomalies in the REMA difference maps (lakes L1, R1, and R2). We were unable to estimate the areas of four lakes (M1, M2, V1, R3) because the REMA strip differences did not show any significant elevation anomalies. For illustrative purposes, we still sketched speculative lake boundaries for these four lakes (Fig. 2d–e) based on ICESat-2 elevation anomaly locations and the REMA mosaic hillshade (Howat et al., 2019).

Figure 2Along-track surface elevation anomalies for each detected subglacial lake, indicating ice surface subsidence (subglacial lake draining) or uplift (subglacial lake filling). ICESat-2 reference ground tracks (RGTs) are shown in panels (a)–(f), and ICESat tracks are shown in panels (a) and (b). Inferred lake boundaries derived from REMA differencing (a, b, and c) are shown as solid red lines, while manually delineated lake boundaries (d, e, f) are shown as dashed red lines. Ice flow direction is represented by black arrows (Gardner et al., 2018). Contours represent surface elevation from REMA (Howat et al., 2019). The bold black line in Panel (e) is the MEaSUREs grounding line (Rignot et al., 2016). Other ice surface elevation changes observed do not meet the >1 m anomaly criterion for active lakes (Sect. 2.3). The background image is the RADARSAT mosaic (Jezek et al., 2013).

2.5 Subglacial lake volume changes and recharge rates

To estimate lake volume changes, we multiplied the REMA-derived lake areas (where available) with the altimetry-based median elevation anomaly within the lake boundary for each repeat track (Smith et al., 2009; Carter et al., 2011). We approximated subglacial water flux by the volume change corresponding to ice surface uplift/deflation over time (Malczyk et al., 2020, 2023). Recharge rates (reported as annual water supply to each lake) were estimated by applying a linear regression vs. volume change and time during the refilling (inter-drainage) period, following Malczyk et al. (2020). We were unable to estimate volume changes for the five lakes without a clear or complete lake boundary in the REMA data. In the absence of further constraints on lake extent changes over time, we assume a constant lake area throughout the fill–drain cycle and a constant overlying ice thickness (Fricker and Scambos, 2009), even though migrating lake boundaries through fill-drain cycles can impact the estimated lake volume changes (Siegfried and Fricker, 2021).

2.6 Hydropotential subglacial water flow mapping

To interpret the satellite-detected lake activity in the context of the broader hydrological system under the ice sheet, we mapped potential subglacial water drainage pathways and their uncertainty based on an ensemble of bed elevation grids generated through stochastic simulation (MacKie et al., 2020, 2021; Shackleton et al., 2023). We made a 1 km grid for the DML region, limited to ca. <73° S to save computation time, and used ice thickness data from Frémand et al. (2023) as a basis for the simulations, after filtering out surveys conducted before 1990, which have limited locational accuracy. Bed elevations were calculated by subtracting ice thicknesses from ice surface elevations extracted from the 500 m REMA mosaic product (Howat et al., 2019), and we also added elevation data from rock outcrops at pixel centroids. To model the measurement variance accounting for spatially varying characteristics of the bed, we chose to cluster the data into 12 regions (Fig. S3) using a k-means-clustering algorithm on measurement coordinates (MacKie et al., 2023). The experimental variogram was calculated using the SciKit GStat Python package (Mälicke, 2022) for normalized bed elevation values in each cluster, giving measurement variances for increasing lag distances in each region. We found the best-fitting statistical models and parameters for each region based on a least-squares analysis for exponential (clusters 0, 5, 6, 9, 11), spherical (clusters 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 10), and Gaussian (cluster 7) model fits (Fig. S3).

We generated an ensemble of 50 equally likely bed elevation grids using a sequential Gaussian simulation algorithm from the GStatSim Python package (MacKie et al., 2023), which simulates bed elevations between measurements along a randomized path over the domain, picking from a Gaussian distribution conditioned at each grid cell by the closest 50 bed elevation measurements and modelled variance. We used the median absolute deviation (MAD) between the 50 grids as a measure of bed elevation uncertainty. Low MAD is associated with regions with a high data density and lower basal roughness, whereas high MAD occurs when there are large distances to the nearby survey profiles and in regions with high basal roughness, where there is greater potential for bed elevation variability between measurements (Shackleton et al., 2023). Figure 1b shows where the MAD is lower than 100 m, indicating regions of relatively low bed uncertainty and higher confidence in simulated subglacial water routing. The simulated bed grids were used together with REMA ice surface elevations (Howat et al., 2019) to estimate gridded ice thicknesses and calculate subglacial hydraulic potential (ϕ) following Shreve (1972), which corresponds to each simulated bed. We assumed that water pressure equals ice overburden pressure and predicted water routing along hydraulic potential gradients assuming a spatially uniform melt rate using a D∞ algorithm (Tarboton, 1997). Subglacial stream probability was calculated from the number of streams predicted per grid cell over the ensemble of the simulated bed. This approach provides uncertainty-constrained water routing predictions where uncertainty can be sourced from either a lack of measurements (i.e. topography is not well enough known), a lack of strong topographic control on water flow, or both. Low-probability streams are therefore associated with regions with sparse data or flat areas where water routing is sensitive to minor fluctuations in bed elevation between simulations. We similarly derived the probability of subglacial hydrological catchment boundaries using the drainage basins for streams predicted in water routing analyses over the simulated bed. We then estimated the ensemble-average upstream catchment area potentially draining towards each altimetry-detected lake (Fig. S4).

3.1 Observed ice surface displacements and interpreted lake activity

We identify seven locations with significant repeated (>1 m) anomalous surface elevation changes over distances of a kilometre or more from ICESat/ICESat-2 repeat tracks, which we interpret as active subglacial lakes. Lake R1 is located 19 km upstream of the Roi Baudouin Ice Shelf grounding line and is crossed by two intersecting ICESat-2 tracks and one ICESat track, all of which show a ∼ 5 km wide elevation anomaly (Fig. 2a; Table 1). Lake L1 is 32 km upstream of the Lazarev Ice Shelf and is crossed by two ICESat tracks and two ICESat-2 tracks (Fig. 2b). Lake R2 is 115 km inland from the Roi Baudouin Ice Shelf and is crossed by only one ICESat-2 track (Fig. 2c). Lake V1 is located 54 km upstream of the Vigridisen Ice Shelf and is crossed by two intersecting ICESat-2 tracks (Fig. 2d). Lakes M1 and M2 are only 10 km apart and are 5 and 15 km upstream of the Muninisen Ice Shelf, respectively (Fig. 2e). Lastly, Lake R3 is 136 km inland from the Roi Baudouin Ice Shelf and is crossed by one track (Fig. 2f), which shows a ∼ 7 km wide elevation anomaly (Fig. S5d).

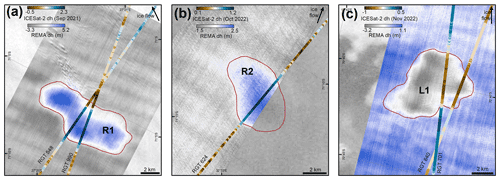

Following Smith et al. (2009), we classify “high-confidence” active lakes as those detected from elevation anomalies in at least two intersecting reference tracks and lakes that are only identified from one satellite altimetry track are classified as “provisionally active”. By this definition, five of the lakes (R1, L1, V1, M1, and M2) are classified as high-confidence and two (R2 and R3) as provisionally active. However, we can independently detect localized elevation anomalies over Lake R2 from REMA strip differencing, supporting the hypothesis that this is an actively filling and draining lake. Three of the seven lakes were confirmed and delineated by REMA strip differencing during 2019–2021 (Fig. 4; L1, R1, R2), and two of these also had intersecting ICESat tracks to extend the change record back to 2003–2009 (Figs. 3 and 5; L1 and R1). Their lake areas range from 21.5 to 40.1 km2 (Table 1). The other four lakes (V1, M1, M2, R3) had no ICESat data and no detectable change between REMA strips, likely due to negligible elevation changes between the dates covered by the strips.

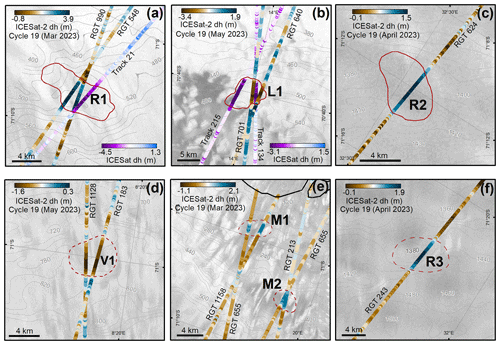

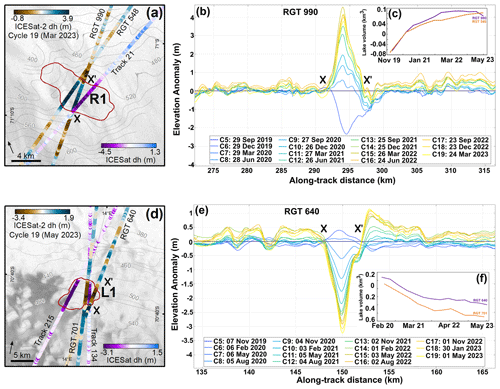

Figure 3Ice surface elevation displacements for an actively filling lake (Lake R1, a–c) upstream of the Roi Baudouin Ice Shelf and an actively draining lake (Lake L1, d–f) upstream of the Lazarev Ice Shelf, both derived from ICESat-2 and ICESat. Significant (>1 m) ice surface elevation anomalies along ICESat-2 reference ground tracks (RGTs) are highlighted by X–X' in each panel. Panels (b) and (e) show ice surface elevation displacements relative to ICESat-2 cycle 3 (April/May 2019). Ice surface elevations from cycle 4 are not plotted, as these were removed by the data quality flag during initial data filtering. Colours correspond to each individual ICESat-2 cycle. Panels (c) and (f) show time series of the estimated lake volume.

Figure 4Ice surface elevation change from REMA strip differencing. (a) Lake R1 and (b) Lake R2, both upstream of the Roi Baudouin Ice Shelf. (c) Lake L1 upstream of the Lazarev Ice Shelf. ICESat-2 elevation changes are relative to (a) April 2019 and (b, c) May 2019. Regions of localized elevation anomaly (blue shading for uplift and grey shading for subsidence) between REMA strip pairs (22 October 2019–10 January 2021 in panel (a), 18 January 2021–28 December 2022 in panel (b), 25 January 2020–15 February 2021 in panel (c)) are delineated by the red lines. These boundaries were outlined manually based on visual assessment. Each example highlights the spatial co-occurrence of significant localized ice surface uplift/subsidence and surface elevation anomalies along the intersecting ICESat-2 reference ground tracks (RGTs). The slight offset between the localized elevation anomalies in the ICESat-2 RGTs and the REMA difference map over Lake R1 in panel (a) could be due to lake boundary migration since the date of the REMA strip (January 2021).

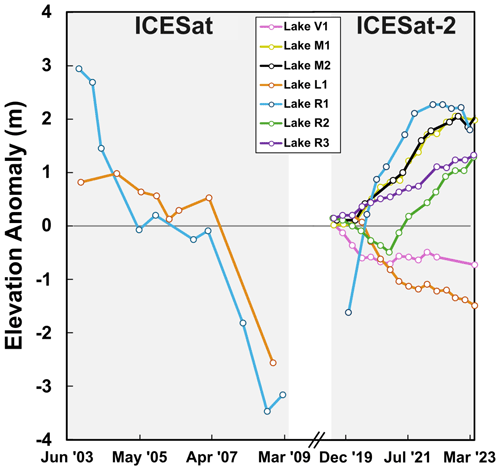

Figure 5ICESat- and ICESat-2-derived ice surface elevation time series calculated as the median elevation anomalies within each lake boundary with respect to elevations in the first available cycle. Lakes L1, R1, and R2 use lake boundaries derived from REMA differencing, and lakes V1, M1, M2, and R3 use boundaries based on locations of significant (>1 m) elevation anomalies over a distance of a kilometre or more.

All seven active lakes are located below sea level and beneath ice thicknesses of 800–1500 m (Fig. 1b). These lakes are typically located in relatively slow-flowing regions: two lakes under 20 m a−1, three lakes between 60 and 90 m a−1, and two beneath slightly faster-flowing tributaries at 152 and 172 m a−1 (Fig. 1b; Table 1). The lakes located close to ice flow divides are beneath especially slow-flowing ice, for example, Lake L1 (Fig. 1b; Table 1). The lakes upstream of the Vigridisen and Muninisen ice shelves are located beneath faster-flowing outlet glaciers (up to 170 m a−1; Gardner et al., 2018).

We assume a one-to-one ratio between ice surface elevation changes and lake volumetric change, following previous studies in Antarctica and Greenland (Smith et al., 2009; Malczyk et al., 2023; Fan et al., 2023). It is possible that some ice surface uplift and subsidence could be influenced by ice flow dynamics, blowing snow, and changes in basal traction, resulting in misinterpretation as subglacial lake activity (Sergienko et al., 2007; Humbert et al., 2018), so this relationship lacks precise quantification (Siegfried and Fricker, 2018). For example, in fast-flowing regions, surface elevation changes can reflect ice flow changes triggered by water displacement at the bed during lake drainage (Smith et al., 2017). Most of the lakes in this study are beneath relatively slow-flowing ice (<100 m a−1), making it unlikely that observed ice surface changes resulted from ice flowing into basal topographic depressions. The patterns of surface elevation change we observe are characteristic of subglacial lake drainage (i.e. deepening towards the lake centre) and lack uplift near localized subsidence, which can be a signal of ice dynamical changes (Carter and Fricker, 2012). We also note that lake widths (inferred from elevation anomaly widths) are large relative to ice thickness (e.g. L1 – ∼ 8.5 ice thicknesses; R1 – ∼ 4 ice thicknesses), whereas ice dynamical effects tend to dominate only when lakes are small relative to ice thickness (Fricker and Scambos, 2009). Ice surface changes over our newly identified lakes (up to 4.5 m) are much larger than those related to wind-driven snow redistribution and firn compaction, typically <0.5 m a−1, based on repeat-track elevation changes elsewhere in the region. Furthermore, the spatial co-occurrence between altimetry- and REMA-derived elevation anomalies and predicted subglacial stream locations (Sect. 3.3) gives us confidence that subglacial meltwater drains towards the observed lakes and that elevation changes are therefore due to subglacial lake activity rather than other surface changes. Therefore, we conclude that the ice surface elevation changes we observe reflect changes in water volume rather than ice dynamics and surface processes, although we acknowledge that actual lake volume changes are still uncertain due to potential migration of lakeshore boundaries through fill–drain cycles (Siegfried and Fricker, 2021).

3.1.1 Lake L1 upstream of Lazarevisen

Over Lake L1, we find steady ice surface subsidence between August 2020 and May 2023 (Fig. 3d–f), suggesting a lake drainage event over a period of at least 2 years and 8 months. This is preceded by a slight ice surface uplift between May 2019 and May 2020, indicating lake refilling. REMA data show slight subsidence beside these tracks during September 2015–December 2016 and January 2020–February 2021, suggesting overall lake volume loss during these two periods (Figs. 4c, S2b). This is consistent with the time series of lake volume derived from ICESat-2, showing the lake steadily draining between May 2020 and May 2023 (Fig. 3f). Elevation anomalies along the two intersecting ICESat tracks continue for 5 km along track 134 and 7 km along track 215, reaching a maximum value of 3 m at the lake centre (Figs. 3d–e, S6b). The lake-averaged elevation anomaly time series over Lake L1 (Fig. 5) reveals positive elevation anomalies from November 2003 to March 2007, followed by a large (>3 m) subsidence over the next 1 year and 8 months, indicating lake drainage. Ice surface displacements show a distinct minimum at the lake centre that tapers out towards the lake edges.

3.1.2 Lakes R1, R2, and R3 upstream of Roi Baudouin

The time series of elevation anomalies from ICESat-2, ICESat, and REMA strip differencing show variable drain and/or fill patterns for these three lakes over the past 2 decades (Figs. 3 and 5). The elevation time series for Lake R1 shows negative anomalies up to −2.4 m in December 2019, followed by a gradual elevation increase to up to 4.5 m in March 2023 (Fig. 3a–b), likely representing lake drainage followed by lake filling over the 3-year-and-5-month period. This is consistent with observed elevation gain (lake filling) from REMA differencing between October 2019 and January 2021 (Fig. 4a). Earlier REMA data indicate a slight subsidence (lake drainage) between December 2016 and December 2017 (Fig. S2a), just ahead of the ICESat-2 observed subsidence in 2019. Time series of lake volume change shows the lake steadily filling between April 2019 and March 2022 (Fig. 3c). More than a decade earlier, ICESat repeat tracks show a steady subsidence across the same area between 2003 and 2009 (Figs. 5, S6a), a sign of lake draining. ICESat-2 data show that Lake R2 was draining between May 2019 and April 2021 and has since been filling through to April 2023 (Fig. S5c). The shape of the lake can be seen from a distinct pattern of uplift between two REMA strips from January 2021 and December 2022 (Fig. 4b). Lastly, over Lake R3, we find gradual ice surface uplift from August 2019 to April 2023 in response to lake filling (Fig. 5).

3.1.3 Lakes V1, M1, and M2 upstream of Vigridisen and Muninisen

We record gradual subsidence up to −1.6 m over Lake V1 from August 2019 to May 2023, indicating slow lake drainage (Figs. 5, S5a). Gradual lake filling over 4 years is apparent from ice surface uplift along a ∼ 2.5 km wide zone of Lake M1 from May 2019 until May 2023 (Figs. 5, S5b). Likewise at Lake M2, lake refilling is found to occur over a ∼ 3-year-and-8-month period, as indicated by ice surface uplift along a ∼ 3 km wide elevation anomaly from September 2019 to June 2023 (Figs. 5, S5b). There is a striking coherence between the filling rates of these two lakes during the ICESat-2 period. Without any further intersecting altimetry tracks or clear change patterns in REMA strips for these lakes, it is difficult to constrain their areas and volume changes. The lack of significant localized elevation changes from REMA differencing could be because they had just drained and not yet refilled in the period covered by the DEM strips or could be due to draining and refilling having roughly balanced each other.

3.2 Subglacial lake volume changes, recharge rates, and water flux

We calculated annual water supply and recharge rates for lakes R1 and L1, where lake boundaries were fully delineated from REMA strip differencing (Fig. 4). Lake R1 steadily gained volume from December 2019 to January 2023 before starting to drain (Figs. 3c, 5). The associated volume gain of 0.13 km3 over 3.5 years corresponds to a yearly recharge rate of 0.03 km3 a−1. Lake L1 gained 0.01 km3 in volume between February 2020 and August 2020 before starting to drain until May 2023 (Fig. 3f). During this half-year period, Lake L1 recharged at a rate of 0.02 km3 a−1. Similarly sized active lakes have been suggested to recharge at similar rates to those reported here, for example Lake Cook E2 (46 km2, 0.05 km3 a−1) and Lake Whillans 2b (25 km2, 0.02 km3 a−1) (Li et al., 2020; Malczyk et al., 2020). Our estimated lake volume gains and losses are of similar magnitudes to the median lake volume change of ∼ 0.12 km3 for 140 active lakes around Antarctica based on their surface elevation histories (Livingstone et al., 2022). However, since we are unable to capture a full drainage or filling cycle for most lakes, actual lake volume changes between minimum and maximum states are likely higher than what we can capture.

To approximate the subglacial meltwater flux entering/leaving the largest lake that we detected (Lake L1), we calculated the rate of volume change corresponding to ice surface uplift/deflation over time (Malczyk et al., 2020). We use Lake L1 as an example for estimating water flux, as it is located close to the grounding line, where topographic uncertainty is relatively low, and has one of the smallest mean upstream catchment areas (0.9 × 104 km2; Table 1). The average subglacial water flux was 4.9 m3 s−1 between November 2003 and May 2023. For comparison, Malczyk et al. (2020) estimated an average water flux of 141 m3 s−1 in 2013 for a network of active lakes upstream of Thwaites Glacier (Thw70, Thw124, Thw142, and Thw170). Modelled upstream melt supply to their lake network ranges from 0.04 to 0.17 km3 a−1 (1.3–5.4 m3 s−1), although these lakes are considerably larger than those in our study (up to 484 km2; Smith et al., 2017). In our water flux estimations, we assume no lake outflow during lake filling, although it is possible that a lake could increase in volume whilst discharging water downstream if a high lake influx exceeds lake outflow (Carter and Fricker, 2012). These assumptions mean that our estimated water flux is likely to be a minimum estimate.

3.3 Predicted subglacial water routing

We simulated an ensemble of 50 equally likely bed elevation grids using sequential Gaussian simulation (Fig. S7, simulations 1–3). The resulting grids are consistent along survey profiles and have continuous, regionally representative roughness simulated between measurements. Throughout the ensemble, water routing analyses predict dendritic networks of subglacial streams routing water from inland towards the grounding line (Fig. S8). This broad pattern of drainage remains consistent over the ensemble, but the kilometre-scale routing of meltwater varies. Stream probability maps (Fig. 1a) show water flow predictions strongly controlled by bed topography in the inland mountain regions where radar measurements are limited, but nevertheless, outcrop surface elevation data help constrain water routing. High stream probability coincides with dense radar survey coverage, for example, surrounding the Nivlisen Ice Shelf, showing the impact of data density on reducing water routing uncertainty. Lower stream probability regions that resemble discontinuous, spatially distributed streams occur between higher-probability streams, for example, inland of the Roi Baudouin Ice Shelf eastward of 27° E (Fig. 6e) and inland of the Muninisen Ice Shelf, often coinciding with widely spaced radar survey profiles. Other regions show inconsistent water routing despite regularly spaced radar profiles, such as within 50 km of the Vigridisen grounding line (Fig. 1a). This reflects an absence of strong topographic features that control the routing of water, so small differences in simulated elevations over the ensemble can reroute water and lead to inconsistent water routing and more diffuse stream predictions.

Figure 6Simulated subglacial water routing and mapped ice-shelf channels in the vicinity of identified active lake areas in this study (red outlines; a–e). Ice-shelf channels (dashed black lines) are from Drews (2015) or are manually delineated from REMA and RADARSAT imagery in this study. The solid black line is the MEaSUREs grounding line (Rignot et al., 2016), the grey lines are radar data locations from Frémand et al. (2023), and the orange triangles are reflectors in airborne radar data interpreted as subglacial water flow outlets (Drews et al., 2017). The background image is the RADARSAT mosaic (Jezek et al., 2013).

We compared our lake observations with the subglacial drainage patterns and found good spatial correspondence over some of the lakes. Predicted water routing shows direct drainage to the western Roi Baudouin Ice Shelf grounding line and identifies likely subglacial outlet locations (Fig. 6a). Lake R1 aligns with several known subglacial water conduits detected at the grounding line in airborne ice-penetrating radar data that align with two sub-ice-shelf channels (Fig. 6a, Drews, 2015; Drews et al., 2017, 2020). This agreement indicates that Lake R1 is likely discharging subglacial meltwater into the ice-shelf cavity through a channelized subglacial conduit system and could contribute to a meltwater plume that forms the sub-ice-shelf channel. However, Lake R1 is 6 km from the closest radar survey profile, and our subglacial stream probabilities highlight the issue that precise drainage routes are less certain here since topographic uncertainty is high (MAD >125 m) in the middle of adjacent radar survey profiles (Fig. 6a). Given the topographic uncertainty in this region, we cannot rule out the potential for lake drainage towards different outlets, for example, if ephemeral subglacial channels close between drainage events. Several ice-shelf channels on the Roi Baudouin Ice Shelf aligned to ice flow direction correspond to the predicted subglacial meltwater outlets beneath the grounded ice sheet and align with the location of lakes R2 and R3 (Fig. 6e). Therefore, lakes R2 and R3 could discharge basal water that is routed towards multiple subglacial outlets at the Roi Baudouin grounding line.

Further west, the probability map of subglacial drainage catchments (Fig. S4) shows, with high confidence, that an extensive catchment of minimum 19 000 km2 is draining towards Lake V1. Downstream water routing predictions vary too much at the kilometre scale to conclusively determine outlet locations at the grounding line, and water routing shows drainage towards the grounding lines of either the Vigridisen Ice Shelf or the neighbouring Fimbulisen Ice Shelf (Fig. 6b). Inland of the Lazarevisen Ice Shelf, predicted subglacial stream and outlet locations become more uncertain, reflecting sparser radar profile spacing (up to 19 km), but they suggest that Lake L1 likely discharges meltwater to the Lazarevisen Ice Shelf grounding line (Fig. 6c). Our water routing analyses also predict high-probability streams connecting lakes M1 and M2, suggesting interconnected lakes that drain into the ice-shelf cavity (Fig. 6d). The predicted subglacial outlet here is close to several sub-ice-shelf channels, indicating that lakes M1 and M2 feed a persistent sub-shelf channel when they drain.

4.1 Lake distributions in the coastal region of the Antarctic Ice Sheet

We identify seven previously undocumented active subglacial lakes in coastal DML at six localities within 5 km of the ice-sheet grounding line, feeding into separate ice shelves (Fig. 1a). The combination of ICESat, ICESat-2, and REMA observations presented here builds upon large-scale repeat satellite altimetry studies of hydrologically active subglacial lakes elsewhere in Antarctica (e.g. Fricker et al., 2007; Fricker and Scambos, 2009; Smith et al., 2009; Siegfried and Fricker, 2021). Only 10 active lakes have been identified previously for the rest of Antarctica within 50 km of the Antarctic-wide grounding line (Livingstone et al., 2022). These 10 known lakes near the grounding line are found on the Antarctic Peninsula (one lake); inland of Totten Glacier (two lakes); and inland of the Rutford (one lake), Mercer (two lakes), Whillans (three lakes), and Kamb ice streams (one lake) (Scambos et al., 2011; Wright and Siegert, 2012; Siegfried and Fricker, 2018).

The location of our identified subglacial lakes demonstrates that thicker, fast-flowing upstream ice is not a pre-requisite for active subglacial lake existence, at least in this part of East Antarctica. All seven lakes are located below sea level and below ice thicknesses of 812–1524 m (Table 1; Fig. 1b). In contrast, the mean ice thickness over previously reported active lakes in Antarctica is 2272 m (Livingstone et al., 2022). The newly detected lakes are generally located beneath slow-flowing ice (<65 m a−1) (Fig. 1b). This contrasts with most known active lakes within 100 km of the Antarctic grounding line, which lie beneath fast-flowing ice (>200 m a−1; Gardner et al., 2018; Livingstone et al., 2022). Two exceptions are lakes KT2 (31.7 km2) and KT3 (38.7 km2) beneath the Kamb Ice Stream, which are comparable in area to our lakes L1 and R1 (31–38 km2) and are located under near-stagnant ice (<2 m a−1) (Kim et al., 2016; Siegfried and Fricker, 2018). Another exception is the active lake system beneath Haynes Glacier in West Antarctica, where the ice flow speed is ∼ 131 m a−1 (Hoffman et al., 2020). Ice thickness above these four lakes (820–1845 m) is within a similar range to our lakes (828–1503 m, Table 1). Much of the grounded ice along the Antarctic coast is slow flowing (<200 m a−1) and lies below sea level within a similar ice thickness range. Consequently, moderately sized active subglacial lakes in the coastal region, similar to the ones presented here at 1–10 km in length and at least 20–40 km2, are likely under-represented in Antarctic-wide inventories yet could store and release significant volumes of water. Large volumes of water stored and released by these subglacial lakes could regulate downstream ice flow (Siegfried et al., 2016) and control the location of subglacial water outlets at the grounding line, driving sub-ice-shelf circulation and melting that could impact ice-shelf stability (e.g. Jenkins, 2011; Gwyther et al., 2023).

That these lakes are located so close to the ice-sheet grounding line beneath relatively slowly flowing ice is unexpected, since the ice-sheet bed is predicted to be cold beneath large parts of the Antarctic coastal region (Pattyn, 2010). In contrast, the thawing ice-sheet bed is typically associated with low geothermal-heat flow and ice flow speeds beneath thick ice and with low surface mass balance at inland regions of Antarctica (Pattyn, 2010; Pattyn et al., 2016). However, the presence of these lakes in coastal DML indicates the existence of temperate basal conditions where meltwater is either accumulating in situ or sourced from pressure changes upstream that trigger drainage further downstream along a channelized subglacial system (Hoffman et al., 2020; Neckel et al., 2021; Dow et al., 2022). The ensemble analyses of bed topographies indicate that the lakes detected have large potential upstream catchments, ranging from 0.5 × 104 km2 (R1) to 2.3 × 104 km2 (V1; Table 1). For lakes located beneath slow-flowing ice, upstream subglacial meltwater supply is primarily controlled by geothermal heat flow (Malczyk et al., 2020), and model results suggest that grounded basal ice across DML is at the pressure melting point (Pattyn, 2010). Therefore, lake recharge is likely regulated by geothermal heat flow and not by frictional heat generated by fast-flowing ice streams or outlet glaciers. The spatial distribution of our lakes can be used to constrain estimates of geothermal heat flow by calculating the minimum geothermal heat flow needed to keep the ice-sheet base at the pressure melting point at the lake locations (Wright and Siegert, 2012). Given that our estimated lake recharge rate for Lake R1 is 0.03 km3 a−1 and that the subglacial drainage catchment is 0.5 × 104 km2, the mean basal melt rate required over the catchment to fill Lake R1 can be approximated as 0.03 km3 a−1/0.5 × 104 km2 = 6 mm a−1. Similarly, for Lake L1, the required basal melt rate can be approximated as 2.2 mm a−1. This is within a reasonable range for coastal DML, where ice-sheet-model experiments have suggested that the mean basal melt rate can reach up to 10 mm a−1 beneath grounded ice (Pattyn, 2010).

None of the newly detected lakes in this study are beneath ice experiencing extensive surface meltwater production or ponding (Arthur et al., 2022; Mahagaonkar et al., 2024), meaning that surface meltwater reaching the ice bed can be discounted as a potential influence on subglacial lake recharge/behaviour. However, we discounted a ∼ 1.8 km wide surface elevation anomaly 5 km inland of the Nivlisen Ice Shelf grounding line as being subglacial in origin because large volumes of supraglacial meltwater are known to pond and flow onto the ice shelf in this region (Dell et al., 2020). Extensive supraglacial lake activity can produce apparently large local elevation change that can be misclassified as subglacial lake activity, although it is possible for subglacial lake drainage to create an ice surface depression that provides a natural basin for surface meltwater to pond (Fan et al., 2023). Additionally, perennially buried lake drainage close to the grounding line can also produce surface elevation change signatures on the order of several metres. Approximately 40 km west of Lake R1, Dunmire et al. (2020) detected average ice surface lowering of ∼ 2.5 m over 1 year and 8 months due to draining of a buried lake, and Sentinel-1 data indicated that the lake drained again 3 years later. In contrast, our results show that ice surface uplift and lowering over the seven subglacial lakes occur over multi-year timescales with a longer cyclicity (∼ 2–5 years).

One possible consideration for the two lakes closest to the grounding line (<16 km; M1 and M2) is that the observed elevation anomalies along these four ICESat-2 tracks reflect seawater intrusion from the ice-shelf grounding zone. Tidal migrations of seawater intrusions up to 20 cm thick along subglacial troughs over timescales of several weeks have been reported from Sentinel-1 DInSAR up to 15 km upstream of the Amery Ice Shelf grounding line (Chen et al., 2023). Robel et al. (2022) also showed with numerical modelling that seawater intrusion over impermeable beds may occur up to tens of kilometres upstream of grounding lines. However, the magnitude of observed elevation anomalies at M1 and M2 (>2 m ice surface uplift) and the multi-year timescale of these changes indicate lake filling rather than intrusion of a centimetre-scale seawater sheet. The predicted presence of subglacial sedimentary basins in coastal DML suggests a permeable ice-sheet bed, meaning seawater intrusion is unlikely (Li et al., 2022).

4.2 Lake filling and draining patterns

We show that the seven lakes fill and drain over periods of several years (Figs. 3, 5). This is consistent with observations from ICESat and ICESat-2 measurements elsewhere in Antarctica, where lakes drain or fill over 3 or 4 years (e.g. Fricker and Scambos, 2009; Fricker et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2009). Similarly, Livingstone et al. (2022) reported lakes in Antarctica exhibiting extended multi-year periods of filling and draining based on the ratio of ice surface uplift and ice surface subsidence in previously identified active lakes.

The limited spatial coverage, observational frequency, and duration of ICESat, ICESat-2, and REMA make it challenging to determine the frequency of lake fill–drain cycles and to resolve potential rapid, episodic lake drainages on daily to monthly timescales. There might also be some undetected smaller lakes, as ICESat-2 repeat-track spacing is up to 9 km in coastal DML, while the smallest lakes we recorded were 5 km wide. Smaller, centimetre-scale surface expressions of lake activity or seawater intrusion on shorter timescales require more detailed or sensitive data like InSAR (Neckel et al., 2021). For example, Neckel et al. (2021) showed that eight lakes of comparable size (7–51 km2) inland of the Jutulstraumen Ice Stream drained in a cascade over 12 d to ∼ 5 months. Consequently, the short-term dynamics and hydrological networks of the new lakes we report may be undersampled, as they could also form interconnected, cascading systems.

4.3 Subglacial water flow

The agreement between our subglacial lake locations, predicted subglacial drainage pathways, and ice-shelf channels indicates that these lakes are actively discharging subglacial meltwater through a channelized subglacial conduit system in coastal DML, likely routing subglacial water into ice-shelf cavities. Previously, this link was made for active lakes beneath fast-flowing ice streams e.g. beneath the MacAyeal Ice Stream and Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica (Fricker et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2017). Further work should compare simultaneous observations of ice surface height anomalies and ice velocity changes to constrain how the subglacial hydrological system co-evolves with subglacial lake fill–drain activity and to determine the influence on ice-shelf dynamics in coastal DML. Similar investigations have been conducted for a series of subglacial drainage events along the northeast Greenland Ice Stream using Sentinel-1 DInSAR (Andersen et al., 2023) and at Thwaites Glacier using Sentinel-1 and GNSS (Hoffman et al., 2020).

Our probability analysis of subglacial water routing shows increased uncertainty in drainage pathways downstream of lakes V1, L1, R1, and R2 (Fig. 6c–f), mainly due to sparse radar survey coverage in these regions. Also, subglacial channels in these regions could be ephemeral and only form during lake drainage events (Smith et al., 2017). Without strong topographic drivers of water flow, it is possible that the routing of meltwater and outlet locations could be variable between drainage events, which could affect the location of subglacial meltwater outlets and consequently local sub-ice-shelf circulation and melt rates. Our analysis highlights regions where more densely spaced radar profiles are needed to reduce uncertainty in basal topography and water routing, for example inland of the Roi Baudouin Ice Shelf and Lazarev Ice Shelf grounding lines. International coordinated programmes like RINGS (Matsuoka et al., 2022; https://scar.org/science/cross/rings, last access: 31 May 2024), involving new radar data collection along and inland of the Antarctic grounding line, should help to close this knowledge gap.

We identified seven local surface height anomalies of magnitudes up to ±4 m using repeated ICESat-2 records in coastal DML, which we interpret as active subglacial lakes. The largest of these lakes was ∼ 9 km long and ∼ 5 km wide. ICESat laser altimetry and REMA strip differencing were used to extend the elevation-change time series over three of these lakes. We detected multiple long-term lake fill–drain cycles from ICESat and ICESat-2 repeat tracks, which coincide spatially with elevation anomalies from differenced REMA strips. Six of the seven lakes coincide with predicted subglacial drainage systems using an ensemble of stochastically simulated bed topographies that consider potential bed roughness between survey profiles. The combination of these datasets indicates that the hydrologically active lakes fill and drain over several years and are linked to channelized subglacial drainage routing meltwater towards the grounding line. In contrast to previously detected subglacial lakes that are typically located under fast-flowing or thicker inland ice, the newly detected lakes are found beneath slower-flowing (17–172 m a−1) ice near the grounding line, with implications for ice-sheet dynamics and freshwater discharge beneath ice shelves. Our results improve knowledge of subglacial meltwater dynamics in this region of East Antarctica and provide new observational data to refine subglacial hydrological models, for example, for validating predicted lake and stream locations. Such refinements are crucial to accurately capture the complexity of dynamic basal conditions and their impact on ice-sheet dynamics.

The code used to process and plot ICESat-2 ATL11 Level 3B version 6 land-ice height data and ICESat GLAH12 version 34 land-ice height data is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13640820 (Arthur, 2024). The code and workflow to simulate the bed elevation grid ensemble and subglacial water flow routing are archived at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13627356 (Shackleton, 2024).

ICESat-2 ATL11 Level 3B version 6 land-ice height data are freely available from https://doi.org/10.5067/ATLAS/ATL11.006 (Smith et al., 2023a). ICESat GLA12 version 34 land ice height data are freely available from https://doi.org/10.5067/ICESAT/GLAS/DATA209 (Zwally et al., 2014). Ice surface velocities from ITS-LIVE (Gardner et al., 2018) are available at https://its-live.jpl.nasa.gov/{#}data-portal. The REMA ice surface DEM strips (Howat et al., 2019) are available from the US Polar Geospatial Center at https://www.pgc.umn.edu/data/rema/. The delineated lake boundaries are available as a shapefile from the Norwegian Polar Data Centre via https://doi.org/10.21334/npolar.2024.ab777130 (Arthur et al., 2024), and the predicted subglacial stream locations produced by our water routing analysis are available as a GeoTIFF from the Norwegian Polar Data Centre via https://doi.org/10.21334/npolar.2024.b438191c (Shackleton et al., 2024).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-19-375-2025-supplement.

JFA analysed the ICESat-2 and REMA data, performed the identification of active lakes, analysed the results and wrote the paper with input from all co-authors. CS and KM carried out stochastic bed topography simulations and the subglacial water flow routing analysis. GM contributed to the conception of the study and processed the ICESat data. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results and to editing of the paper.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

The bed elevation simulations were performed on resources provided by Sigma2 – the National Infrastructure for High-Performance Computing and Data Storage in Norway through project NN10061K.

Jennifer F. Arthur and Calvin Shackleton are funded by the Norges Forskningsråd FRINATEK project (project number 315246). Jennifer F. Arthur is also funded by a national infrastructure grant from the Norwegian Space Agency to the Norwegian Polar Institute (contract number 74CO2303).

This paper was edited by Huw Horgan and reviewed by Emma MacKie and one anonymous referee.

Andersen, J. K., Rathmann, N., Hvidberg, C. S., Grinsted, A., Kusk, A., Merryman Boncori, J. P., and Mouginot, J.: Episodic subglacial drainage cascades below the Northeast Greenland Ice Stream, Geophys. Res. Lett., 50, e2023GL103240, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GL103240, 2023.

Arthur, J.: DML-SubglacialLakes, Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13640820, 2024.

Arthur, J., Shackleton, C., Matsuoka, K., Moholdt, G., and van Oostveen, J.: Active subglacial lakes in coastal Dronning Maud Land, East Antarctica derived from ICESat-2 and ICESat, Norwegian Polar Institute [data set], https://doi.org/10.21334/npolar.2024.ab777130, 2024.

Arthur, J. F., Stokes, C. R., Jamieson, S. S., Rachel Carr, J., Leeson, A. A., and Verjans, V.: Large interannual variability in supraglacial lakes around East Antarctica, Nat. Commun., 13, 1711, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29385-3, 2022.

Boening, C., Lebsock, M., Landerer, F., and Stephens, G.: Snowfall-driven mass change on the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, Geophys. Res. Lett., 39, L21501, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL053316, 2012.

Brenner, A. C., DiMarzio, J. P., and Zwally, H. J.: Precision and accuracy of satellite radar and laser altimeter data over the continental ice sheets, IEEE T. Geosci. Remote, 45, 321–331, https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2006.887172, 2007.

Brunt, K. M., Smith, B. E., Sutterley, T. C., Kurtz, N. T., and Neumann, T. A.: Comparisons of Satellite and Airborne Altimetry With Ground-Based Data From the Interior of the Antarctic Ice Sheet, Geophys. Res. Lett., 48, e2020GL090572, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL090572, 2021.

Carter, S. P. and Fricker, H. A.: The supply of subglacial meltwater to the grounding line of the Siple Coast, West Antarctica, Ann. Glaciol., 53, 267–280, https://doi.org/10.3189/2012AoG60A119, 2012.

Carter, S. P., Fricker, H. A., Blankenship, D. D., Johnson, J. V., Lipscomb, W. H., Price, S. F., and Young, D. A.: Modeling 5 years of subglacial lake activity in the MacAyeal Ice Stream (Antarctica) catchment through assimilation of ICESat laser altimetry, J. Glaciol., 57, 1098–1112, https://doi.org/10.3189/002214311798843421, 2011.

Chartrand, A. M. and Howat, I. M.: Basal channel evolution on the Getz Ice Shelf, West Antarctica, J. Geophys. Res., 125, e2019JF005293, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JF005293, 2020.

Chen, H., Rignot, E., Scheuchl, B., and Ehrenfeucht, S.: Grounding zone of Amery Ice Shelf, Antarctica, from differential synthetic-aperture radar interferometry, Geophys. Res. Lett., 50, e2022GL102430, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL102430, 2023.

Dell, R., Arnold, N., Willis, I., Banwell, A., Williamson, A., Pritchard, H., and Orr, A.: Lateral meltwater transfer across an Antarctic ice shelf, The Cryosphere, 14, 2313–2330, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-14-2313-2020, 2020.

Dow, C. F., Ross, N., Jeofry, H., Siu, K., and Siegert, M. J.: Antarctic basal environment shaped by high-pressure flow through a subglacial river system, Nat. Geosci., 15, 892–898, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-022-01059-1, 2022.

Drews, R.: Evolution of ice-shelf channels in Antarctic ice shelves, The Cryosphere, 9, 1169–1181, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-9-1169-2015, 2015.

Drews, R., Pattyn, F., Hewitt, I. J., Ng, F. S. L., Berger, S., Matsuoka, K., Helm, V., Bergeot, N., Favier, L., and Neckel, N.: Actively evolving subglacial conduits and eskers initiate ice shelf channels at an Antarctic grounding line, Nat. Commun., 8, 15228, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15228, 2017.

Drews, R., Schannwell, C., Ehlers, T. A., Gladstone, R., Pattyn, F., and Matsuoka, K.: Atmospheric and oceanographic signatures in the ice shelf channel morphology of Roi Baudouin Ice Shelf, East Antarctica, inferred from radar data, J. Geophys. Res., 125, e2020JF005587, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JF005587, 2020.

Dunmire, D., Lenaerts, J. T. M., Banwell, A. F., Wever, N., Shragge, J., Lhermitte, S., Drews, R., Pattyn, F., Hansen, J. S. S., Willis, I. C., and Miller, J.: Observations of buried lake drainage on the Antarctic Ice Sheet, Geophys. Res. Lett., 47, e2020GL087970, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL087970, 2020.

Fan, Y., Hao, W., Zhang, B., Ma, C., Gao, S., Shen, X., and Li, F.: Monitoring the Hydrological Activities of Antarctic Subglacial Lakes Using CryoSat-2 and ICESat-2 Altimetry Data, Remote Sens., 14, 898, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14040898, 2022.

Fan, Y., Ke, C.-Q., Shen, X., Xiao, Y., Livingstone, S. J., and Sole, A. J.: Subglacial lake activity beneath the ablation zone of the Greenland Ice Sheet, The Cryosphere, 17, 1775–1786, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-17-1775-2023, 2023.

Flament, T., Berthier, E., and Rémy, F.: Cascading water underneath Wilkes Land, East Antarctic ice sheet, observed using altimetry and digital elevation models, The Cryosphere, 8, 673–687, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-8-673-2014, 2014.

Frémand, A. C., Fretwell, P., Bodart, J. A., Pritchard, H. D., Aitken, A., Bamber, J. L., Bell, R., Bianchi, C., Bingham, R. G., Blankenship, D. D., Casassa, G., Catania, G., Christianson, K., Conway, H., Corr, H. F. J., Cui, X., Damaske, D., Damm, V., Drews, R., Eagles, G., Eisen, O., Eisermann, H., Ferraccioli, F., Field, E., Forsberg, R., Franke, S., Fujita, S., Gim, Y., Goel, V., Gogineni, S. P., Greenbaum, J., Hills, B., Hindmarsh, R. C. A., Hoffman, A. O., Holmlund, P., Holschuh, N., Holt, J. W., Horlings, A. N., Humbert, A., Jacobel, R. W., Jansen, D., Jenkins, A., Jokat, W., Jordan, T., King, E., Kohler, J., Krabill, W., Kusk Gillespie, M., Langley, K., Lee, J., Leitchenkov, G., Leuschen, C., Luyendyk, B., MacGregor, J., MacKie, E., Matsuoka, K., Morlighem, M., Mouginot, J., Nitsche, F. O., Nogi, Y., Nost, O. A., Paden, J., Pattyn, F., Popov, S. V., Rignot, E., Rippin, D. M., Rivera, A., Roberts, J., Ross, N., Ruppel, A., Schroeder, D. M., Siegert, M. J., Smith, A. M., Steinhage, D., Studinger, M., Sun, B., Tabacco, I., Tinto, K., Urbini, S., Vaughan, D., Welch, B. C., Wilson, D. S., Young, D. A., and Zirizzotti, A.: Antarctic Bedmap data: Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) sharing of 60 years of ice bed, surface, and thickness data, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 15, 2695–2710, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-2695-2023, 2023.

Fretwell, P., Pritchard, H. D., Vaughan, D. G., Bamber, J. L., Barrand, N. E., Bell, R., Bianchi, C., Bingham, R. G., Blankenship, D. D., Casassa, G., Catania, G., Callens, D., Conway, H., Cook, A. J., Corr, H. F. J., Damaske, D., Damm, V., Ferraccioli, F., Forsberg, R., Fujita, S., Gim, Y., Gogineni, P., Griggs, J. A., Hindmarsh, R. C. A., Holmlund, P., Holt, J. W., Jacobel, R. W., Jenkins, A., Jokat, W., Jordan, T., King, E. C., Kohler, J., Krabill, W., Riger-Kusk, M., Langley, K. A., Leitchenkov, G., Leuschen, C., Luyendyk, B. P., Matsuoka, K., Mouginot, J., Nitsche, F. O., Nogi, Y., Nost, O. A., Popov, S. V., Rignot, E., Rippin, D. M., Rivera, A., Roberts, J., Ross, N., Siegert, M. J., Smith, A. M., Steinhage, D., Studinger, M., Sun, B., Tinto, B. K., Welch, B. C., Wilson, D., Young, D. A., Xiangbin, C., and Zirizzotti, A.: Bedmap2: improved ice bed, surface and thickness datasets for Antarctica, The Cryosphere, 7, 375–393, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-7-375-2013, 2013.

Fricker, H. A. and Padman, L.: Ice shelf grounding zone structure from ICESat laser altimetry, Geophys. Res. Lett., 33, L15502, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL026907, 2006.

Fricker, H. A. and Scambos, T.: Connected subglacial lake activity on lower Mercer and Whillans ice streams, West Antarctica, 2003–2008, J. Glaciol., 55, 303-315, https://doi.org/10.3189/002214309788608813, 2009.

Fricker, H. A., Scambos, T., Bindschadler, R., and Padman, L.: An Active Subglacial Water System in West Antarctica Mapped from Space, Science, 315, 1544–1548, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1136897, 2007.

Fricker, H. A., Scambos, T., Carter, S., Davis, C., Haran, T., and Joughin, I.: Synthesizing multiple remote-sensing techniques for subglacial hydrologic mapping: application to a lake system beneath MacAyeal Ice Stream, West Antarctica, J. Glaciol., 56, 187–199, https://doi.org/10.3189/002214310791968557, 2010.

Fricker, H. A., Carter, S. P., Bell, R. E., and Scambos, T.: Active lakes of Recovery Ice Stream, East Antarctica: a bedrock-controlled subglacial hydrological system, J. Glaciol., 60, 1015–1030, https://doi.org/10.3189/2014JoG14J063, 2014.

Gardner, A. S., Moholdt, G., Scambos, T., Fahnstock, M., Ligtenberg, S., van den Broeke, M., and Nilsson, J.: Increased West Antarctic and unchanged East Antarctic ice discharge over the last 7 years, The Cryosphere, 12, 521–547, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-12-521-2018, 2018 (data available at: https://its-live.jpl.nasa.gov/#data-portal, last access: 1 May 2024).

Goel, V., Martín, C., and Matsuoka, K.: Evolution of ice rises in the Fimbul Ice Shelf, Dronning Maud Land, over the last millennium, Ant. Sci., 36, 110–124, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954102023000330, 2024.

Goeller, S., Steinhage, D., Thoma, M., and Grosfeld, K.: Assessing the subglacial lake coverage of Antarctica, Ann. Glaciol., 57, 109–117, https://doi.org/10.1017/aog.2016.23, 2016.

Goldberg, D., Twelves, A., Holland, P., and Wearing, M. G.: The Non-Local Impacts of Antarctic Subglacial Runoff, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 128, e2023JC019823 https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JC019823, 2023.

Gray, L., Joughin, I., Tulaczyk, S., Spikes, V. B., Bindschadler, R., and Jezek, K.: Evidence for subglacial water transport in the West Antarctic Ice Sheet through three-dimensional satellite radar interferometry, Geophys. Res. Lett., 32, L03501, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004GL021387, 2005.

Gwyther, D. E., Dow, C. F., Jendersie, S., Gourmelen, N., and Galton-Fenzi, B. K.: Subglacial freshwater drainage increases simulated basal melt of the Totten Ice Shelf, Geophys. Res. Lett., 50, e2023GL103765, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GL103765, 2023.

Hodgson, D. A., Jordan, T. A., Ross, N., Riley, T. R., and Fretwell, P. T.: Drainage and refill of an Antarctic Peninsula subglacial lake reveal an active subglacial hydrological network, The Cryosphere, 16, 4797–4809, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-16-4797-2022, 2022.

Hoffman, A. O., Christianson, K., Shapero, D., Smith, B. E., and Joughin, I.: Brief communication: Heterogenous thinning and subglacial lake activity on Thwaites Glacier, West Antarctica, The Cryosphere, 14, 4603–4609, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-14-4603-2020, 2020.

Howat, I. M., Porter, C., Smith, B. E., Noh, M.-J., and Morin, P.: The Reference Elevation Model of Antarctica, The Cryosphere, 13, 665–674, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-13-665-2019, 2019 (data available at: https://www.pgc.umn.edu/data/rema/, last access: : 2 November 2024).

Humbert, A., Steinhage, D., Helm, V., Beyer, S., and Kleiner, T.: Missing evidence of widespread subglacial lakes at Recovery Glacier, Antarctica, J. Geophys. Res., 123, 2802–2826, https://doi.org/10.1029/2017JF004591, 2018.

Jenkins, A.: Convection-driven melting near the grounding lines of ice shelves and tidewater glaciers, J. Phys. Oceanogr., 41, 2279–2294, https://doi.org/10.1175/JPO-D-11-03.1, 2011.

Jezek, K. C., Curlander, J. C., Carsey, F., Wales, C., and Barry, R.G.: RAMP AMM-1 SAR Image Mosaic of Antarctica, Version2, National Snow and Ice Data Center [data set], https://doi.org/10.5067/8AF4ZRPULS4H, 2013.

Kim, B.-H., Lee, C.-K., Seo, K.-W., Lee, W. S., and Scambos, T.: Active subglacial lakes and channelized water flow beneath the Kamb Ice Stream, The Cryosphere, 10, 2971–2980, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-10-2971-2016, 2016.

Kohler, J., Neumann, T. A., Robbins, J. W., Tronstad, S., and Melland, G.: ICESat elevations in Antarctica along the 2007–09 Norway–USA traverse: Validation with ground-based GPS, IEEE T. Geosci. Remote, 51, 1578–1587, https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2012.2207963, 2012.

Lepp, A. P., Simkins, L. M., Anderson, J. B., Clark, R. W., Wellner, J. S., Hillenbrand, C. D., Smith, J. A., Lehrmann, A. A., Totten, R., Larter, R. D., and Hogan, K. A.: Sedimentary signatures of persistent subglacial meltwater drainage from Thwaites Glacier, Antarctica, Front. Earth Sci., 10, 863200, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2022.863200, 2022.

Li, L., Aitken, A. R., Lindsay, M. D., and Kulessa, B.: Sedimentary basins reduce stability of Antarctic ice streams through groundwater feedbacks, Nat. Geosci., 15, 645–650, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-022-00992-5, 2022.

Li, Y., Lu, Y., and Siegert, M. J.: Radar sounding confirms a hydrologically active deep-water subglacial lake in East Antarctica, Front. Earth Sci., 8, 294, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2020.00294, 2020.

Livingstone, S. J., Li, Y., Rutishauser, A., Sanderson, R. J., Winter, K., Mikucki, J. A., Björnsson, H., Bowling, J. S., Chu, W., Dow, C. F., and Fricker, H. A.: Subglacial lakes and their changing role in a warming climate, Nat. Rev. Earth Environ., 3, 106–124, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-021-00246-9, 2022.

MacKie, E. J., Schroeder, D. M., Caers, J., Siegfried, M. R., and Scheidt, C.: Antarctic topographic realizations and geostatistical modeling used to map subglacial lakes, J. Geophys. Res.-Earth, 125, e2019JF005420, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JF005420, 2020.

MacKie, E. J., Schroeder, D. M., Zuo, C., Yin, Z., and Caers, J.: Stochastic modeling of subglacial topography exposes uncertainty in water routing at Jakobshavn Glacier, J. Glaciol., 67, 75–83, https://doi.org/10.1017/jog.2020.84, 2021.

MacKie, E. J., Field, M., Wang, L., Yin, Z., Schoedl, N., Hibbs, M., and Zhang, A.: GStatSim V1.0: a Python package for geostatistical interpolation and conditional simulation, Geosci. Model Dev., 16, 3765–3783, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-16-3765-2023, 2023.

Mahagaonkar, A., Moholdt, G., Glaude, Q., and Schuler, T. V.: Supraglacial lake evolution and its drivers in Dronning Maud Land, East Antarctica, J. Glaciol., 70, e49, https://doi.org/10.1017/jog.2024.66, 2024.

Malczyk, G., Gourmelen, N., Goldberg, D., Wuite, J., and Nagler, T.: Repeat subglacial lake drainage and filling beneath Thwaites Glacier, Geophys. Res. Lett., 47, e2020GL089658, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL089658, 2020.

Malczyk, G., Gourmelen, N., Werder, M., Wearing, M., and Goldberg, D.: Constraints on subglacial melt fluxes from observations of active subglacial lake recharge, J. Glaciol., 69, 1900–1914, https://doi.org/10.1017/jog.2023.70, 2023.

Mälicke, M.: SciKit-GStat 1.0: a SciPy-flavored geostatistical variogram estimation toolbox written in Python, Geosci. Model Dev., 15, 2505–2532, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-15-2505-2022, 2022.

Markus, T., Neumann, T., Martino, A., Abdalati, W., Brunt, K., Csatho, B., Farrell, S., Fricker, H., Gardner, A., Harding, D., and Jasinski, M.: The Ice, Cloud, and land Elevation Satellite-2 (ICESat-2): science requirements, concept, and implementation, Remote Sens. Environ., 190, 260–273, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2016.12.029, 2017.

Matsuoka, K., Forsberg, R., Ferraccioli, F., Moholdt, G., and Morlighem, M.: Circling Antarctica to unveil the bed below its icy edge, Eos, 103, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022EO220276, 2022.

Medley, B., Lenaerts, J. T. M., Dattler, M., Keenan, E., and Wever, N.: Predicting Antarctic net snow accumulation at the kilometer scale and its impact on observed height changes, Geophys. Res. Lett., 49, e2022GL099330, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL099330, 2022.

Moholdt, G., Nuth, C., Hagen, J. O., and Kohler, J.: Recent elevation changes of Svalbard glaciers derived from ICESat laser altimetry, Remote Sens. Environ., 114, 2756–2767, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2010.06.008, 2010.

Moon, J., Lee, H., and Lee, H.: Elevation Change of CookE2 Subglacial Lake in East Antarctica Observed by DInSAR and Time-Segmented PSInSAR, Remote Sens., 14, 4616, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14184616, 2022.

Morlighem, M.: MEaSUREs BedMachine Antarctica, Version 3, NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center [data set], https://doi.org/10.5067/FPSU0V1MWUB6, 2022.

Mouginot, J., Scheuchl B., and Rignot E.: MEaSURE's Antarctic Boundaries for IPY 2007–2009 from Satellite Radar, Version 2, NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center [data set], https://doi.org/10.5067/AXE4121732AD, 2017.

Neckel, N., Franke, S., Helm, V., Drews, R., and Jansen, D.; Evidence of Cascading Subglacial Water Flow at Jutulstraumen Glacier (Antarctica) Derived From Sentinel-1 and ICESat-2 Measurements, Geophys. Res. Lett., 48, e2021GL094472, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL094472, 2021.

Pattyn, F.: Antarctic subglacial conditions inferred from a hybrid ice sheet/ice stream model, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 295, 451–461, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2010.04.025, 2010.

Pattyn, F., Carter, S. P., and Thoma, M.: Advances in modelling subglacial lakes and their interaction with the Antarctic ice sheet, Philos. T. R. Soc. A, 374, 20140296, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2014.0296, 2016.

Pratap, B., Dey, R., Matsuoka, K., Moholdt, G., Lindbäck, K., Goel, V., Laluraj, L., and Thamban, M.: Three-decade spatial patterns in surface mass balance of the Nivlisen Ice Shelf, central Dronning Maud Land, East Antarctica, J. Glaciol., 68, 174–186, https://doi.org/10.1017/jog.2021.93, 2022.

Rignot, E., Mouginot, J., and Scheuchl, B.: MEaSUREs Antarctic Grounding Line from Differential Satellite Radar Interferometry, Version 2, NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center [data set], https://doi.org/10.5067/IKBWW4RYHF1Q, 2016.