the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Sea ice reduction in the Barents–Kara Sea enhances June precipitation in the Yangtze River basin

Tianli Xie

Renhe Zhang

Bingyi Wu

Peng Zhang

This study investigates the influence of June sea surface temperature (SST) and sea ice in the Barents–Kara Sea (BKS) on concurrent rainfall variability in the Yangtze River basin from 1982 to 2021 using both observational data and numerical experiments. The observed decrease in BKS sea ice and the corresponding increase in SST during June aligns with enhanced precipitation in the Yangtze River basin on an interannual timescale. The BKS thermal forcing induces an equivalent barotropic Rossby wave train in the middle and upper troposphere, which propagates southeastward to the Northwest Pacific (NWP). This Rossby wave train features two positive centers over the BKS and NWP and one negative center above Baikal Lake. The strengthened NWP subtropical high and upper-level westerly jet contribute to increased rainfall in the Yangtze River basin by enhancing moisture transport and anomalous ascending motions. These findings provide important implications for predicting summer rainfall in East Asia.

- Article

(2849 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

East Asia, characterized by its dense population and swift economic growth, experiences a precipitation belt during the early summer that stretches from the Yangtze River basin in China to the central-southern regions of Japan and the southern part of South Korea. This rain belt, known as the Mei-yu rainband in China, exhibits a quasi-stationary state with pronounced year-to-year variability. Fluctuations in precipitation directly affect local water resources, agricultural policies, disaster prevention, and various socioeconomic factors (Ninomiya and Murakami, 1987; Fu and Teng, 1988; Xu et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2004; Ding et al., 2020).

Sea surface temperature (SST) variability in the tropics is an important driver for interannual variability in summer rainfall over the East Asia region (Xie et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017). The El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) in the Pacific Ocean has been identified as the dominant forcing of Mei-yu rainfall variability (Huang and Wu, 1989; Huang et al., 2004; Xie et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017; Ding et al., 2020). During post-El Niño summers, the Mei-yu rainband in East Asia tends to increase with a low-level Northwest Pacific (NWP) anomalous anticyclone (AAC). The NWP AAC develops rapidly during an El Niño winter (Zhang et al., 1996) and lasts through the following summer by means of many mechanisms (Huang and Zhang, 1997; Wang et al., 2000; Xie et al., 2009; Rong et al., 2010). However, recent studies found that the excessive Mei-yu rainfall and NWP AAC are often but not always induced by ENSO, such as in the year of 2020. For the 2020 summer, the Mei-yu rainfall in the Yangtze River basin surpassed historical records dating back to 1961, causing severe flooding, while the 2019–2020 El Niño event was very weak. Indeed, the extreme Mei-yu event of 2020 is largely due to the extreme Indian Ocean dipole (IOD) event of 2019 (Takaya et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2021). The Indian Ocean warming in summer 2020 induced the NWP AAC and intensified the upper-level westerly jet over the Yangtze River basin, causing heavy rainfall along the Yangtze River (Zhou et al., 2021). Positive SST anomalies in May over the North Atlantic can also enhance rainfall in June over the Yangtze River basin (Zheng and Wang, 2021).

In addition to tropical SST forcings, sea ice variations in the Arctic have received increasing attention with regard to their impact on climate in the Eurasian region since the 20th century (Gao et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2017; Hou et al., 2022). Since the 20th century, there have been rapid changes in both SST and sea ice in the Arctic (Comiso, 2006; Francis and Hunter, 2007; Stroeve et al., 2007; Screen and Simmonds, 2010). The Arctic sea ice variations could influence the East Asian summer monsoon by modulating the wave train along the Asian jet. The declining sea ice in the Arctic during spring and summer leads to an enhancement of summer rainfall in northeastern China (Niu et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2021), in central China between the Yangtze River and the Yellow River (Wu et al., 2009; He et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018; Shen et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2021), in the former Indo-China Peninsula, and in the Philippines and to decreased rainfall over the Mei-yu front zone (Guo et al., 2014). For instance, He et al. (2018) demonstrated that June sea ice variability in the Barents Sea can trigger a meridional wave train extending to the mid-latitudes, which further influences the Silk Road pattern and consequently impacts East Asian precipitation in August. Wu et al. (2009) found that variations in spring sea ice concentrations in the Arctic Ocean and the Greenland Sea can trigger a Eurasian wave train that extends from northern Europe to northeastern Asia, thereby influencing summer rainfall patterns in China.

However, there is ongoing debate regarding whether changes in Arctic sea ice can influence mid-latitude climate and atmospheric circulation (Cohen et al., 2020). A recent study found that the decrease in Arctic sea ice has little impact on summer mean precipitation in the Yangtze River basin and South China, with its main impact being observed in the mid-latitude and high-latitude regions of East Asia (Wu et al., 2023). Over the past few decades, there has been a substantial reduction in the extent of summer sea ice in the Arctic (Onarheim et al., 2018; Kumar et al., 2021). The Barents–Kara Sea (BKS), which is recognized for experiencing one of the most rapid rates of sea ice decline in the Arctic, demonstrates significantly elevated SSTs during the summer months compared to the average (Carvalho and Wang, 2020; Yang et al., 2023). Nevertheless, the simultaneous impact of sea ice and SST variations in the BKS on summer rainfall in the Yangtze River basin remains unclear and contentious. The present study investigates the influence of sea ice and SST variations in the BKS on the interannual fluctuations of rainfall within the Yangtze River basin. We show that enhanced Mei-yu rainfall in June instead of summer mean over the Yangtze River basin is associated with BKS sea ice loss and an SST increase.

We use monthly precipitation data from the Climate Prediction Center Merged Analysis of Precipitation (CMAP) and the Climatic Research Unit Time Series (CRU TS); monthly sea ice concentration (SIC) and SST data from the Hadley Centre; and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts ERA5 reanalysis dataset, which includes monthly surface air temperature (SAT), geopotential height (GPH), sea level pressure (SLP), surface net thermal radiation, surface net solar radiation, surface sensible heat flux, surface latent heat flux, specific humidity, zonal and meridional winds, and vertical velocity.

To test the robustness of the results, we employed the NCAR Community Atmosphere Model Version 5 (CAM5; Neale et al., 2012) to examine the potential influence of observed changes in BKS sea ice and SST on summer precipitation in East Asia. The CAM5 was run with a global horizontal resolution of about 2° (F19_F19) and 30 levels in the vertical. The atmospheric model of each ensemble member was forced by monthly sea ice and SST data from the Hadley SST and sea ice datasets, covering the observed BKS region (65–80° N, 0–80° E) from 1982 to 2021. In other oceanic regions, SST and SIC forcings exhibited climatological averages characterized by a seasonal cycle. Meanwhile, other forcings, including the concentration of greenhouse gases, aerosols, and solar radiation, are all set to fixed values during the entire integration period. The ensemble average was calculated from the simulation results of 20 ensemble members to determine the collective model response to the observed variations in BKS SIC and SST.

The climatological mean is defined as the average of the data from 1982 to 2021. To mitigate the effects of global warming, a method for removing linear trends was employed before the analysis. The influence of May SST in the western North Atlantic was eliminated before analysis, as suggested by Zheng and Wang (2021), which does not change the main conclusion of the present study. The study describes the atmospheric wave activity using the wave activity flux (WAF) as derived by Takaya and Nakamura (2001). In the following figures, positive values indicate downward radiative fluxes, while negative values represent upward radiative fluxes.

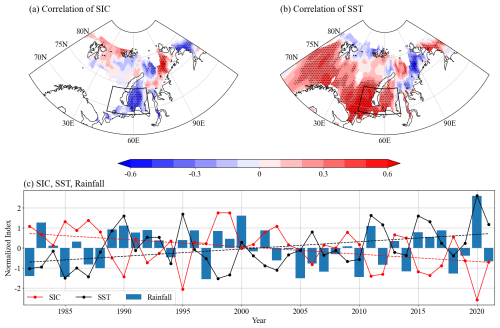

Figure 1Distribution of correlation coefficients between the June rainfall index over the Yangtze River basin (27.5–34.7° N, 103–122° E; Fig. 2a) and (a) SIC anomalies (omitted SD below 0.11) and (b) SST anomalies (omitted SD below 0.36°) in the BKS during 1982–2021. The areas significant at the 90 % confidence level are dotted. (c) Normalized time series of the regionally averaged SIC and/or SST in the BKS (69–74° N, 45–69° E; black boxes) and rainfall in the Yangtze River basin. The dashed lines denote the linear trends.

3.1 Dominant features and relationships between BKS sea ice and/or SST and rainfall in the Yangtze River basin

Figure 1a and b show the distribution of correlation coefficients between June rainfall in the Yangtze River basin and BKS SIC and/or SST. Since the 1980s, prominent fluctuations in SIC have been documented in the BKS and coastal areas, exhibiting relatively high standard deviations (0.25 over the Kara Sea). There is a significant negative correlation between the June precipitation in the Yangtze River basin and sea ice in the Kara Sea (r < −0.4) and a positive correlation with SST in both the Barents Sea and the Kara Sea (r > 0.4). A correlation of 0.27 reaches the 90 % significance level based on Student's t test. The significant correlations between BKS SIC and/or SST and June rainfall in the Yangtze River basin indicate that the melting of sea ice and the resulting changes in SST in the BKS may have an impact on June precipitation in East Asia on the interannual timescale.

To measure the interannual variations in sea ice and SST, SIC and SST indices are established over the BKS region (69–74° N, 45–69° E). Over the last 4 decades, there has been a consistent decrease (−0.37 per decade) in SIC and a noteworthy warming trend (0.36 °C per decade) in SST, which are highly correlated with each other on the interannual timescale at −0.96. The reduction in sea ice results in a larger expanse of open water being exposed to sunlight than under a normal state, which has a lower albedo, consequently causing greater absorption of solar radiation and an increase in SST. The positive SST anomalies contribute to the acceleration of sea ice melting, leading to the establishment of a positive feedback loop (Kellogg, 1975; Curry et al., 1995; Screen and Simmonds, 2012). From 1982 to 2021, the correlation coefficients between June rainfall in the Yangtze River basin and BKS SIC and/or SST reached −0.37 and 0.44; both are significant at the 90 % confidence level, indicating the influence of BKS SIC and/or SST variations on East Asian summer precipitation.

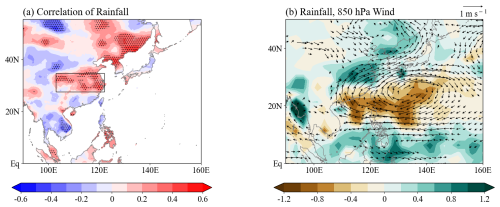

Figure 2(a) Correlation map of East Asia rainfall with concurrent BKS SST index in June during 1982–2021. The areas significant at the 90 % confidence level are dotted. (b) Anomalies of rainfall (shading; unit: mm d−1) and 850 hPa wind (vector; unit: m s−1; omitted below 0.15 m s−1) regressed onto the BKS SST index in June.

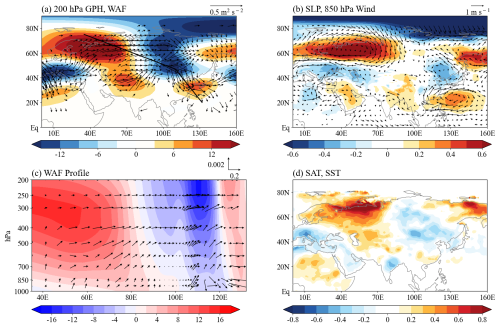

Figure 3Anomalies of (a) 200 hPa GPH (shading; unit: gpm) and horizontal WAF (vector; unit: m2 s−2; omitted below 0.05 m2 s−2), (b) SLP (shading; unit: mbar) and 850 hPa wind (vector; unit: m s−1; omitted below 0.1 m s−1), (c) vertical–horizontal cross-section averaged within 20–75° N, 35–132° E for WAF (vector; unit: m2 s−2) and GPH (shading; unit: gpm), (d) SAT (shading; unit: °; on land) and SST (shading; unit: °; on ocean) regressed onto the BKS SST index in June.

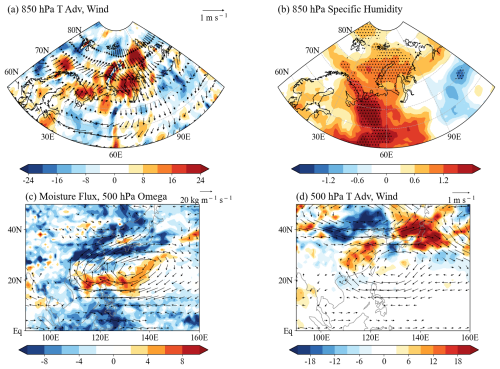

Figure 4Anomalies of (a) 850 hPa horizontal temperature advection (shading; unit: 10−7 K s−1) and 850 hPa wind (vector; unit: m s−1),; (b) 850 hPa specific humidity (shading; unit: 103 g kg−1), with significant areas at 90 % confidence dotted; (c) moisture flux (vector; unit: ; omitted below 5 ) and 500 hPa omega (shading; unit: 10−3 Pa s−1); (d) 500 hPa horizontal temperature advection (shading; unit: 10−7 K s−1) and 500 hPa wind (vector; unit: m s−1; omitted below 0.15 m s−1) regressed onto the BKS SST index in June.

3.2 The mechanism of BKS sea ice and/or SST affecting rainfall in the Yangtze River basin

We use CMAP and CRU precipitation data to verify and ensure the consistency and reliability of our results. Figure 2a depicts the distribution of correlation coefficients between BKS SST and precipitation in June. In the Yangtze River basin, a positive correlation between SST and precipitation has been observed. This indicates that an increase in June SST in the BKS region corresponds with increased precipitation in the Yangtze River basin, supporting the findings shown in Fig. 1. Associated with an increase in Mei-yu rainfall, convective activities are depressed over the South China Sea and NWP region (Fig. 2b), while the low-level circulation anomalies show an AAC pattern and a high SLP (Fig. 3b) anomaly. These patterns are largely consistent with summer mean anomalies during the post-El Niño summer, known as the Indo-western Pacific Ocean capacitor (IPOC) mode (Xie et al., 2016). Indeed, the correlation between the June BKS SST index and the preceding DJF Niño-3.4 index amounts to −0.02. The above regressions remain unchanged after removing the ENSO effect in the preceding winter. In addition, there are positive rainfall anomalies over northeastern Asia, with a low-level anomalous cyclonic circulation anomaly pattern (Zhang et al., 2021). However, in July and August, correlations between BKS SIC and/or SST and Yangtze River rainfall become insignificant (not shown), possibly due to the northward shift of the mean rain belt. This intraseasonal difference is consistent with findings by Wu et al. (2023) indicating that the anomalous melting of Arctic sea ice primarily affects East Asian summer seasonal mean precipitation in middle- and high-latitude regions, with minimal impacts on rainfall in the Yangtze River basin. Further investigation is needed to understand these monthly differences.

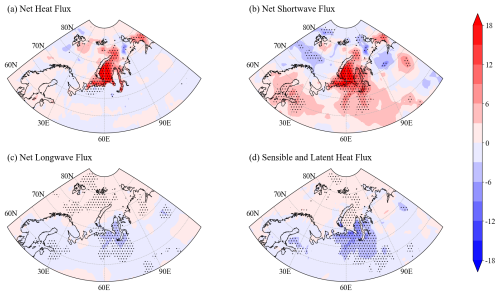

Figure 5Anomalies of (a) net heat flux, (b) net shortwave flux, (c) net longwave flux, (d) sensible heat flux and latent heat flux (shading; unit: W m−2) regressed onto the BKS SST index in June. The areas significant at the 90 % confidence level are dotted.

Figure 3 depicts the regressed atmospheric circulation and temperature anomalies against the BKS SST index. A Rossby wave pattern, characterized by a sequence of positive, negative, and positive GPH anomalies, emerges from the Arctic and travels to East Asia at 200 hPa (Fig. 3a). This atmospheric pattern exhibits an equivalent barotropic vertical structure, extending from 200 hPa to the surface (Fig. 3a and b). This is accompanied by the propagation of WAF (Fig. 3c), signifying a significant influence of atmospheric activity on rainfall in East Asia. Specifically, a pronounced positive GPH anomaly is present over the BKS and northern Siberia. According to Kim et al. (2022), Siberia frequently encounters elevated temperatures during the summer season and heatwaves linked to high-pressure heat domes contribute to the development of regional high-pressure systems, aligning with the findings of our study. The anomalous anticyclonic circulation linked to high pressure (Fig. 3b) facilitates the northward transport of warm air (Fig. 4a), causing the sea ice melting and positive SST anomalies in the BKS (Fig. 3d). The reduced sea ice coverage increases open water and decreases the sea ice albedo, reflects less solar radiation (Fig. 5b), and enhances the ocean warming (Fig. 3d) as positive ice albedo feedback. Furthermore, the melting of snow cover in northern Siberia (Fig. 5d) contributes to the increase in the low-level water vapor (Fig. 4b), which effectively traps outward longwave radiation and induces upward sensible and latent heat fluxes in the northern Siberia region (Fig. 5c and d). This enhances the high-pressure system, which exhibits a quasi-barotropic structure with upward wave activities (Fig. 3c). As the high-pressure system (Fig. 3a and b) intensifies, it increases shortwave radiation (Fig. 5b), accelerating snowmelt, thus reinforcing the high-pressure system in a positive feedback loop. However, the intensified net heat flux (Fig. 5a) from the atmosphere to the ocean in the BKS region is not a direct cause of sea ice melting. Rather, it is a consequence of the decreased sea ice concentration in this region (Kellogg, 1975; Curry et al., 1995; Screen and Simmonds, 2012). The melting sea ice reflects less solar radiation from the ocean to the atmosphere, thereby increasing the downward net heat flux (Fig. 5a), which is mostly contributed by the incoming shortwave radiation (Fig. 5b).

To further elucidate the propagation characteristics of the Rossby wave train, an in-depth analysis was conducted on the WAF profiles along the Rossby wave path (Fig. 3c). The overlaid arrows represent the horizontal and vertical components of the WAF. This illustration reveals a pronounced transmission of Rossby waves from the BKS region to East Asia within the mid-to-upper atmosphere. Simultaneously, the thermal high-pressure induced by surface heat anomalies facilitates the upward propagation of WAF, thereby enhancing the energy of Rossby waves. The GPH anomalies manifest a distinct quasi-barotropic structure characterized by “+-+” anomalies along the propagation pathway, with the negative (positive) GPH anomaly center located over Baikal Lake and northeastern Asia (the NWP region), accompanied by low-level anomalous cyclones (anticyclones). This quasi-barotropic structure contributes to the dissipation of WAF, ultimately reaching East Asia. These observations offer additional evidence that the Arctic domain, particularly the BKS, serves as a significant source of variability in East Asian precipitation. The relay of wave energy could be a fundamental physical mechanism through which sea ice or SST influences precipitation patterns in East Asia.

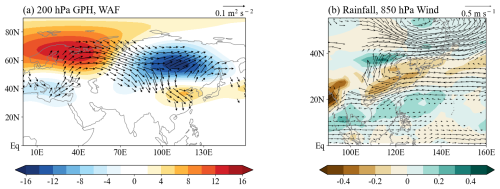

Figure 6The 20-member ensemble mean anomalies of (a) 200 hPa GPH (shading; unit: gpm) and horizontal WAF (vector; unit: m2 s−2; omitted below 0.02 m2 s−2), (b) rainfall (shading; unit: mm d−1) and 850 hPa wind (vector; unit: m s−1; omitted below 0.03 m s−1) regressed onto the second principle component (PC2) from the EOF analysis during 1982–2021.

In East Asia, the other high-pressure center of the quasi-barotropic Rossby wave influences the NWP region. This high-pressure system strengthens the NWP subtropical high and reduces local convective activities (Figs. 2b and 3a and b). The accompanying 850 hPa wind anomalies show an anomalous anticyclone pattern, which can transport increased warm water vapor to the Mei-yu front (Fig. 4c). The low-pressure center of the quasi-barotropic Rossby wave located over Baikal Lake is accompanied by a low-level anomalous cyclone. The southwesterly of the NWP AAC and the northwesterly of the anomalous cyclone over northeastern Asia converge in the Yangtze River basin, contributing to the enhanced rainfall there (Fig. 2b). In addition, coupled with localized upward vertical velocities (Fig. 4c), this leads to atmospheric uplift, convective development, and the observed positive precipitation anomalies (Fig. 2b). At the 500 hPa level, the intensification of the westerly jet acts as a conduit for warm advection toward the precipitation zones, as shown in Fig. 4d, promoting convection and leading to the observed increase in precipitation within the region as feedback between latent heating and circulation anomalies (Lu and Lin, 2009; Sampe and Xie, 2010; Kosaka et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2021). All three of the above processes contribute to increased rainfall in the Yangtze River basin during June.

The investigation of teleconnections between Arctic climate anomalies and East Asian meteorological patterns employs empirical orthogonal function (EOF) analysis using the CAM5 model, focusing on GPH deviations within the wave train corridor spanning 30–80° N, 40–140° E. Figure 6a reveals an elevated GPH anomaly centered over the BKS and the northwestern Eurasian sector, consistently with observed atmospheric configurations, which is the leading singular value decomposition (SVD) mode between GPH at 250 hPa and SST fields during 1982–2021. The designated horizontal WAF originates from the BKS and extends southeastward from northern Siberia, dynamically reinforced by regional high-pressure systems. This flux intensifies near Baikal Lake and maintains its trajectory toward the Yangtze River basin, illustrating the wave train's role in modulating the East Asian climate. A noticeable westward shift in the modeled high-pressure center over the BKS compared to the observations may be linked to prominent North Atlantic SST anomalies, a deviation from climatological data requiring further investigation. In addition, the positions of both the low-pressure center near Baikal Lake (Fig. 6a) and the positive Mei-yu rain belt anomalies (Fig. 6b) are northward shifted compared to the observations; this is due to inherent biases in the CAM5 model, with a northward displacement of the mean westerly jet and the climatological Mei-yu rain belt over the Yangtze River basin in June and July (not shown), consistently with CAM6 model (Zhou et al., 2021).

Overall, the findings suggest that significant June anomalies in sea ice and SST within the BKS trigger anomalous local surface heating. This thermal disturbance serves as a genesis point for teleconnection patterns, propagating across the Eurasian landmass and significantly impacting the East Asian climate system.

The present study investigates the significant influence of the BKS on East Asian precipitation, utilizing both observational data and numerical experiments to delineate the underlying mechanisms. The findings highlight the complex interplay between June sea ice and SST anomalies in the BKS and concurrent variations in precipitation across East Asia, as mediated by complex atmospheric circulation patterns.

The analysis reveals a distinctive “+-+” quasi-barotropic structure of the GPH field in the mid-to-upper level, indicating the propagation of Rossby wave trains across the Eurasian continent. Notably, the BKS and northern Siberia emerge as regions of pronounced high-pressure anomalies, facilitating anticyclonic circulations. These circulation anomalies induce atmospheric warm advection and enhance shortwave radiation absorption, contributing to ocean warming, sea ice melting, and subsequent SST increases. The amplification of shortwave radiation absorption by the ocean not only enhances local water vapor content but also escalates downward longwave radiation and latent and sensible heat fluxes, exacerbating the regional temperature rise. The reduced sea ice reflects less solar radiation and enhances the ocean warming following the ice albedo feedback, which, together with melting snow cover in the northern Siberian region, contributes to the high-pressure system through thermal processes. A positive feedback loop between oceanic and atmospheric dynamics cultivates the development of a robust heat dome, extending from the lower to the upper troposphere. Furthermore, the low-pressure (high-pressure) anomaly center over Baikal Lake and northeastern Asia (the NWP region) is accompanied by a low-level anomalous cyclone (anticyclone). The southwesterly of the NWP AAC and the northwesterly of the anomalous cyclone over northeastern Asia converge in the Yangtze River basin, aligning with the intensification of warm advection by intensified westerly jets, contributing to the enhanced Mei-yu rainfall over the Yangtze River basin.

Our exploration into the sea ice and/or SST in the BKS not only illuminates the rapid and profound implications of global warming on the Arctic but also introduces new dimensions to understanding precipitation variations in East Asia. As the Arctic continues to experience warming, its influence on East Asian precipitation patterns is likely to grow in terms of both significance and complexity. Therefore, further research and dialogue regarding the changing Arctic environment and its impact on East Asian precipitation are crucial. Enhanced observational efforts and comprehensive analyses are imperative to refine our understanding of these regional climate patterns. Such advancements will be instrumental in improving predictions of future climate changes and the evolution of the Mei-yu band and will underpin more effective disaster management and climate adaptation strategies.

SST and SIC are obtained from the Met Office Hadley Centre (https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadisst/data/download.html, last access: 16 March 2025; Rayner et al., 2003). Precipitation datasets are from NOAA (https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.cmap.html, last access: 16 March 2025; Xie and Arkin, 1997) and the University of East Anglia Climatic Research Unit (https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/timm/grid/CRU_TS_1_2.html, last access: 16 March 2025; Mitchell et al., 2004). The ERA5 datasets are available online at https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.6860a573 (Hersbach et al., 2023). Data from the numerical experiments have been deposited in GitHub (https://github.com/Tianli-Xie/numerical-experiments-for-precipitation-in-the-Yangtze-River-basin, last access: 16 March 2025) and at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15034783 (Xie, 2025).

TX analyzed the observational data and the results of the numerical experiments. ZQZ conceived the study and conducted the numerical simulations. ZQZ and TX prepared the paper. All the authors actively discussed the results and made significant contributions to the writing of the final version of the paper.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

We wish to thank Shuoyi Ding, Xuanwen Zhang, and Ruonan Zhang for the useful discussions. This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 42288101 and 42175025) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2023YFF0806700).

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 42288101 and 42175025) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2023YFF0806700).

This paper was edited by Xichen Li and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Carvalho, K. and Wang, S.: Sea surface temperature variability in the Arctic Ocean and its marginal seas in a changing climate: Patterns and mechanisms, Global Planet. Change, 193, 103265, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2020.103265, 2020.

Chen, X., Dai, A., Wen, Z., and Song, Y.: Contributions of Arctic sea-ice loss and East Siberian atmospheric blocking to 2020 record-breaking Meiyu-Baiu rainfall, Geophys. Res. Lett., 48, e2021GL092748, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL092748, 2021.

Cohen, J., Zhang, X., Francis, J., Jung, T., Kwok, R., Overland, J., Ballinger, T., Bhatt, U., Chen, H., and Coumou, D.: Divergent consensuses on Arctic amplification influence on midlatitude severe winter weather, Nature Climate Change, 10, 20–29, 2020.

Comiso, J. C.: Abrupt decline in the Arctic winter sea ice cover, Geophys. Res. Lett., 33, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL027341, 2006.

Curry, J. A., Schramm, J. L., and Ebert, E. E.: Sea ice-albedo climate feedback mechanism, J. Climate, 8, 240–247, 1995.

Ding, Y., Liang, P., Liu, Y., and Zhang, Y.: Multiscale variability of Meiyu and its prediction: A new review, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 125, e2019JD031496, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JD031496, 2020.

Francis, J. A. and Hunter, E.: Drivers of declining sea ice in the Arctic winter: A tale of two seas, Geophys. Res. Lett., 34, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GL030995, 2007.

Fu, C. and Teng, X.: The relationship between ENSO and climate anomaly in China during the summer time, Science Atmospheric Sinica, 12, 133–141, 1988.

Gao, Y., Sun, J., Li, F., He, S., Sandven, S., Yan, Q., Zhang, Z., Lohmann, K., Keenlyside, N., and Furevik, T.: Arctic sea ice and Eurasian climate: A review, Adv. Atmos. Sci., 32, 92–114, 2015.

Guo, D., Gao, Y., Bethke, I., Gong, D., Johannessen, O. M., and Wang, H.: Mechanism on how the spring Arctic sea ice impacts the East Asian summer monsoon, Theor. Appl. Climatol., 115, 107–119, 2014.

He, S., Gao, Y., Furevik, T., Wang, H., and Li, F.: Teleconnection between sea ice in the Barents Sea in June and the Silk Road, Pacific–Japan and East Asian rainfall patterns in August, Adv. Atmos. Sci., 35, 52–64, 2018.

Hersbach, H., Bell, B., Berrisford, P., Biavati, G., Horányi, A., Muñoz Sabater, J., Nicolas, J., Peubey, C., Radu, R., Rozum, I., Schepers, D., Simmons, A., Soci, C., Dee, D., and Thépaut, J.-N.: ERA5 monthly averaged data on pressure levels from 1940 to present, Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) [data set], https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.6860a573 (last access: 16 March 2025), 2023.

Hou, Y., Cai, W., Holland, D. M., Cheng, X., Zhang, J., Wang, L., Johnson, N. C., Xie, F., Sun, W., and Yao, Y.: A surface temperature dipole pattern between Eurasia and North America triggered by the Barents–Kara sea-ice retreat in boreal winter, Environ. Res. Lett., 17, 114047, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac9ecd, 2022.

Huang, R. and Wu, Y.: The influence of ENSO on the summer climate change in China and its mechanism, Adv. Atmos. Sci., 6, 21–32, 1989.

Huang, R. and Zhang, R.: A diagnostic study of the interaction between ENSO cycle and East Asian monsoon circulation, Memorial Papers to Prof. Zhao Jiuzhang, 93, 109, China Science Press, China, ISBN 7-03-006402-X/P, 1997.

Huang, R., Chen, W., Yang, B., and Zhang, R.: Recent advances in studies of the interaction between the East Asian winter and summer monsoons and ENSO cycle, Adv. Atmos. Sci., 21, 407–424, 2004.

Kellogg, W. W.: Climatic feedback mechanisms involving the polar regions, Climate of the Arctic, 111–116, Proceedings of the Climate of the Arctic, Climate of the Arctic Conference, Fairbanks, Alaska, USA, 1975.

Kim, J.-H., Kim, S.-J., Kim, J.-H., Hayashi, M., and Kim, M.-K.: East Asian heatwaves driven by Arctic-Siberian warming, Sci. Rep., 12, 18025, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22628-9, 2022.

Kosaka, Y., Xie, S.-P., and Nakamura, H.: Dynamics of interannual variability in summer precipitation over East Asia, J. Climate, 24, 5435–5453, 2011.

Kumar, A., Yadav, J., and Mohan, R.: Spatio-temporal change and variability of Barents–Kara sea ice, in the Arctic: Ocean and atmospheric implications, Sci. Total Environ., 753, 142046, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142046, 2021.

Lu, R. and Lin, Z.: Role of subtropical precipitation anomalies in maintaining the summertime meridional teleconnection over the western North Pacific and East Asia, J. Climate, 22, 2058–2072, 2009.

Mitchell, T. D., Carter, T. R., Jones, P. D., Hulme, M., and New, M.: A comprehensive set of high-resolution grids of monthly climate for Europe and the globe: the observed record (1901 -2000) and 16 scenarios (2001–2100), Tyndall Centre Working Paper 55, Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK, 30 pp., https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/timm/grid/CRU_TS_1_2.html (last access: 16 March 2025), 2004.

Neale, R. B., Chen, C.-C., Gettelman, A., Lauritzen, P. H., Park, S., Williamson, D. L., Conley, A. J., Garcia, R., Kinnison, D., and Lamarque, J.-F.: Description of the NCAR community atmosphere model (CAM 5.0), NCAR Technical Note Ncar/TN-486+ STR, 274 pp., National Center for Atmospheric Research, CO, USA, https://doi.org/10.5065/wgtk-4g06, 2012.

Ninomiya, K. and Murakami, T.: The early summer rainy season (Baiu) over Japan, Monsoon Meteorology, edited by: Chang, C.-P. and Krishnamurti, T. N., Oxford University Press, New York, ISBN 0195042549, 93–121, 1987.

Niu, T., Zhao, P., and Chen, L.: Effects of the sea-ice along the North Pacific on summer rainfall in China, Acta Meteorol. Sin., 17, 52–64, 2003.

Onarheim, I. H., Eldevik, T., Smedsrud, L. H., and Stroeve, J. C.: Seasonal and regional manifestation of Arctic sea ice loss, J. Climate, 31, 4917–4932, 2018.

Rayner, N. A., Parker, D. E., Horton, E. B., Folland, C. K., Alexander, L. V., Rowell, D. P., Kent, E. C., and Kaplan, A.: Global Analyses of Sea Surface Temperature, Sea Ice, and Night Marine Air Temperature Since the Late Nineteenth Century, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 108, 4407, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JD002670, 2003 (data available at: https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadisst/data/download.html, last access: 16 March 2025).

Rong, X., Zhang, R., and Li, T.: Impacts of Atlantic sea surface temperature anomalies on Indo-East Asian summer monsoon-ENSO relationship, Chinese Sci. Bull., 55, 2458–2468, 2010.

Sampe, T. and Xie, S.-P.: Large-scale dynamics of the meiyu-baiu rainband: Environmental forcing by the westerly jet, J. Climate, 23, 113–134, 2010.

Screen, J. A. and Simmonds, I.: Increasing fall-winter energy loss from the Arctic Ocean and its role in Arctic temperature amplification, Geophys. Res. Lett., 37, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010GL044136, 2010.

Screen, J. A. and Simmonds, I.: Declining summer snowfall in the Arctic: Causes, impacts and feedbacks, Clim. Dynam., 38, 2243–2256, 2012.

Shen, H., He, S., and Wang, H.: Effect of summer Arctic sea ice on the reverse August precipitation anomaly in eastern China between 1998 and 2016, J. Climate, 32, 3389–3407, 2019.

Stroeve, J., Holland, M. M., Meier, W., Scambos, T., and Serreze, M.: Arctic sea ice decline: Faster than forecast, Geophys. Res. Lett., 34, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GL029703, 2007.

Takaya, K. and Nakamura, H.: A formulation of a phase-independent wave-activity flux for stationary and migratory quasigeostrophic eddies on a zonally varying basic flow, J. Atmos. Sci., 58, 608–627, 2001.

Takaya, Y., Ishikawa, I., Kobayashi, C., Endo, H., and Ose, T.: Enhanced Meiyu-Baiu rainfall in early summer 2020: Aftermath of the 2019 super IOD event, Geophys. Res. Lett., 47, e2020GL090671, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL090671, 2020.

Wang, B., Wu, R., and Fu, X.: Pacific–East Asian teleconnection: how does ENSO affect East Asian climate?, J. Climate, 13, 1517–1536, 2000.

Wu, B., Zhang, R., Wang, B., and D'Arrigo, R.: On the association between spring Arctic sea ice concentration and Chinese summer rainfall, Geophys. Res. Lett., 36, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009GL037299, 2009.

Wu, B., Yang, K., and Francis, J. A.: A cold event in Asia during January–February 2012 and its possible association with Arctic sea ice loss, J. Climate, 30, 7971–7990, 2017.

Wu, B., Li, Z., Zhang, X., Sha, Y., Duan, X., Pang, X., and Ding, S.: Has Arctic sea ice loss affected summer precipitation in North China?, Int. J. Climatol., 43, 4835–4848, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.8119, 2023.

Xie, P. and Arkin, P. A.: Global Precipitation: A 17-Year Monthly Analysis Based on Gauge Observations, Satellite Estimates, and Numerical Model Outputs, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 78, 2539–2558, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0477(1997)078<2539:GPAYMA>2.0.CO;2, 1997 (data available at: https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.cmap.html, last access: 16 March 2025).

Xie, S.-P., Hu, K., Hafner, J., Tokinaga, H., Du, Y., Huang, G., and Sampe, T.: Indian Ocean capacitor effect on Indo–western Pacific climate during the summer following El Niño, J. Climate, 22, 730–747, 2009.

Xie, S.-P., Kosaka, Y., Du, Y., Hu, K., Chowdary, J. S., and Huang, G.: Indo-western Pacific Ocean capacitor and coherent climate anomalies in post-ENSO summer: A review, Adv. Atmos. Sci., 33, 411–432, 2016.

Xie, T.: Tianli-Xie/numerical-experiments-for-precipitation-in-the-Yangtze-River-basin: numerical-experiments-for-precipitation-in-the-Yangtze-River-basin, Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15034783, 2025.

Xu, H., Zhang, W., Lang, X., Guo, X., Ge, W., Dang, R., and Takao, T.: The use of dual—Doppler radar data in the study of 1998 meiyu frontal precipitation in huaihe river basin, Adv. Atmos. Sci., 17, 403–412, 2000.

Yang, M., Qiu, Y., Huang, L., Cheng, M., Chen, J., Cheng, B., and Jiang, Z.: Changes in Sea Surface Temperature and Sea Ice Concentration in the Arctic Ocean over the Past Two Decades, Remote Sens.-Basel, 15, 1095, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15041095, 2023.

Zhang, P., Wu, Z., and Jin, R.: How can the winter North Atlantic Oscillation influence the early summer precipitation in Northeast Asia: effect of the Arctic sea ice, Clim. Dynam., 56, 1989–2005, 2021.

Zhang, R., Sumi, A., and Kimoto, M.: Impact of El Niño on the East Asian monsoon, J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II, 74, 49–62, 1996.

Zhang, R., Min, Q., and Su, J.: Impact of El Niño on atmospheric circulations over East Asia and rainfall in China: Role of the anomalous western North Pacific anticyclone, Sci. China-Earth Sci., 60, 1124–1132, 2017.

Zhang, R., Sun, C., and Li, W.: Relationship between the interannual variations of Arctic sea ice and summer Eurasian teleconnection and associated influence on summer precipitation over China, Chinese J. Geophys., 61, 91–105, 2018.

Zheng, J. and Wang, C.: Influences of three oceans on record-breaking rainfall over the Yangtze River Valley in June 2020, Sci. China-Earth Sci., 64, 1607–1618, 2021.

Zhou, Z.-Q., Xie, S.-P., and Zhang, R.: Historic Yangtze flooding of 2020 tied to extreme Indian Ocean conditions, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 118, e2022255118, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2022255118, 2021.